Health

Four lessons from STAT’s malaria vaccine development story

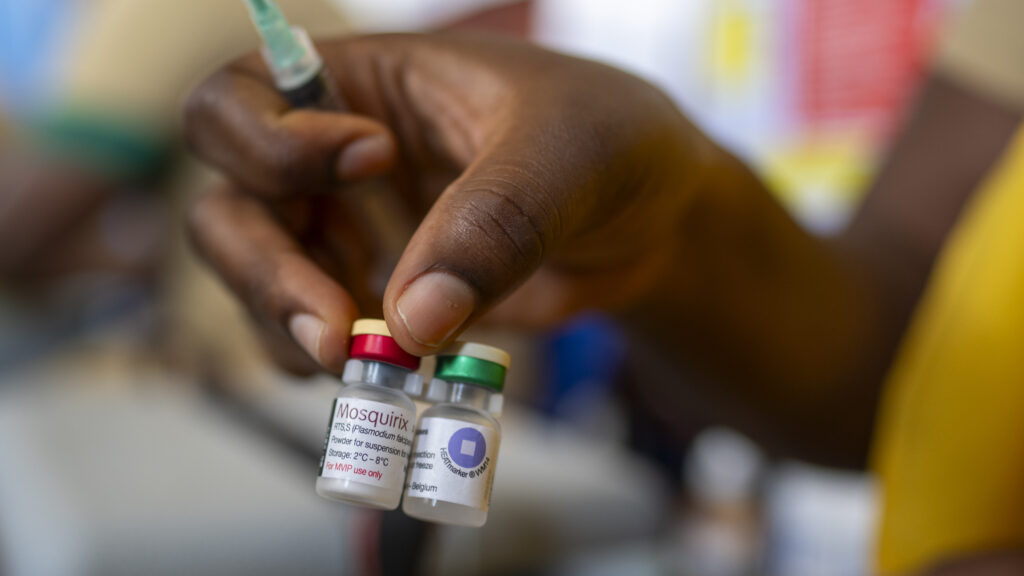

For the first time the world begins rolling out malaria vaccines to children in sub-Saharan Africa. The story of those vaccines’ development, a decades-long effort that stretched from labs in New York, England and Belgium to clinical trial sites in a number of African countries, is detailed in a special STAT report published Thursday.

Below are four insights into what the history of malaria shots reveals about vaccine development, especially for neglected diseases that mainly affect low-income countries.

Science builds

Sometimes scientific discoveries are attributed to individual champions. But when you talk to researchers, they emphasize that science really does have a snowball effect, with initial findings enabling future breakthroughs. This was clear in the case of the malaria vaccines.

For example, the shots’ architects relied on foundational work by researchers like Ruth and Victor Nussenzweig of New York University, a couple who met during medical school in Brazil. Joe Cohen, who helped lead the development of the RTS,S malaria vaccine at GSK, leveraged the company’s previous work on a hepatitis B vaccine. When researchers at the University of Oxford built their own malaria vaccine, called R21, twenty years later, they took advantage of advances in basic research tools that had emerged in the meantime.

The vaccines underscore how scientific success often relies on people solving tough problems for years — especially when the target is as complex as a parasite like the one that causes malaria — and no single discovery is made on its own.

Commercial prospects influence vaccine development

It is common knowledge that pharmaceutical companies are not always interested in developing drugs or vaccines for diseases if they cannot get good returns from them, including many conditions of the world’s poorest countries. That dynamic — on top of the scientific challenge inherent in trying to prevent malaria — helps explain why the shots took so long to arrive.

In the case of RTS,S, GSK was deeply involved in inventing, promoting and manufacturing the vaccine for decades. But a lot of work and money was also put in by other groups to support the vaccine at particularly precarious times – and to encourage GSK to keep the program alive. If profits had been promised, the process might have gone more smoothly.

Experts involved in the development of the vaccines also pointed to another financial factor that delayed them. With potentially lucrative products on the line, companies will do everything they can to expedite development, including staging future testing and scaling up production while previous studies are still ongoing. But with RTS,S, the research teams could only really start planning and fundraising for their next research once the previous research had been fully completed and demonstrated success; Otherwise they wouldn’t have been able to get donors on board. It explains why there were often long gaps between the main studies on RTS,S.

A possible alternative path

If it will be difficult to get pharmaceutical companies on board to develop more vaccines and treatments for neglected diseases, what can be done?

The experience with R21 points toward a different path, says Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute in Oxford and one of the vaccine’s developers. The Oxford team worked directly with the Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer, which subsequently funded the Phase 3 trial of R21.

Hill is now encouraging other academic teams working on neglected diseases to work directly with major manufacturers. This way, researchers do not have to tempt a biopharmaceutical company to become a development partner. The economics of vaccine development for diseases in the world’s poorest countries don’t match those companies’ business models, Hill said. They want to sell a vaccine dose for a few hundred dollars, but the international agencies that buy vaccines for low-income countries can only afford a few dollars per dose.

Manufacturers have a different model.

“This is what I’m preaching about right now,” Hill said of working with manufacturers. “They will look at manufacturability, they will look at production costs. “When they find out they can make it for one dollar and sell it for two dollars, they’re happy.”

The Covid question

The world rallied to develop Covid-19 vaccines in record time. Many African researchers who spoke to STAT pointed to this achievement as showing that scientists, companies and regulators know how to speed up vaccine development when they want to. So where has that urgency gone with malaria?

To be clear, there are important differences between malaria and Covid that have affected the speed at which their respective vaccines were developed. First, the coronavirus that causes Covid is a much easier target to build a vaccine against. Another distinction: unlike Covid, infants are the primary population targeted by malaria shots. But researchers first had to demonstrate the vaccines’ safety in older populations before they could ethically test the shots in young people, adding years to development timelines. There are also other interventions – including mosquito nets and chemoprevention – that can help reduce the risk of malaria. The world didn’t have many defense mechanisms when Covid hit.

Yet efforts to develop malaria vaccines have not come close to the kind of public health campaign or funding that greeted the Covid pandemic. Many experts – in Africa, Europe and the US – cite the fact that the disease affects almost entirely people in poor countries as one reason why the world has not moved as quickly.

“If you can see the speed that Covid had, from the alarm and then to getting the vaccine – it was less than a year,” said Eusebio Macete, a Mozambican researcher. “So people are asking, what’s wrong with the communicable diseases in Africa? Why would we let people die for years without those tools?”