Finance

Why are interest rates important?

Interest rates are important, but not in the way most people assume. To see why, it may be helpful to start with an analogy. Why is inflation important?

If you ask the average customer, they will tell you that inflation is clearly bad because the public has to pay more for the things they buy. But if you pick up an economics textbook, this factor is nowhere mentioned as “cost of inflation.” That’s because when people spend more on goods, other people earn more by selling those goods. In itself, higher prices are a zero-sum game.

That doesn’t mean high inflation isn’t a problem; I believe it is a very serious problem. But it’s not a problem because most people assume it’s a problem.

The same goes for interest rates. Most people think (wrongly) that low interest rates are good for the economy. Stock traders know better, and stocks fell sharply on Friday even as longer-term yields fell. As with inflation, interest rates can be important, but not for the reasons you might expect.

I suspect most people make the same mistake as consumers when it comes to inflation, based on personal experiences. For example, they might imagine how lower rates could make it easier to buy a house or car. But interest rates are a zero-sum game. When one pays more interest, the other receives more interest.

I suppose you could argue that a change in interest rates could cause some sort of “redistribution,” although it’s hard to say exactly how. When interest rates are low, the media complain that big banks benefit and retirees with savings accounts are disadvantaged. When rates are high, the media complains that credit card holders suffer and big banks benefit. But even if falling interest rates redistributed money to lower-income people, that doesn’t mean it would help the economy. Low rates also tend to reduce speeds because people have more incentives to hoard cash. As always, it depends on why the interest rate is changing.

Consider the following two statements:

1. It is nonsense to talk about the influence of interest rates on the economy. It would be like talking about the impact of a change in oil prices on the oil market.

2. It makes a lot of sense to talk about how monetary policy affects the economy.

If both are true, then interest rates obviously cannot be monetary policy. So what is monetary policy?

3. Monetary policy is a set of actions by central banks that influence the supply and demand for base money, often with the aim of influencing macro aggregates such as prices, employment and/or NGDP.

So what do interest rates have to do with monetary policy?

1. Before 2008, the Fed targeted the fed funds rate by directing its open market desk to buy and sell government bonds. This policy had a direct impact on the supply of base money, and indirectly on interest rates.

2. After 2008, the Fed continued to change the supply of base money (via QE), but also used the tool of interest on bank reserves to influence the demand for base money.

3. The Fed also influences the demand for base money by influencing the expected growth rate of the NGDP. Faster NGDP growth trends to reduce real demand for base money.

Remark: These three effects do not all work in the same direction!

This is the most important point that so many people miss; even many economists overlook this problem. (If you’re familiar with the recent debate, the first two mechanisms are emphasized by Keynesians, and the third has implications related to neo-fisheryism.)

Because monetary policy affects interest rates in a complex and often contradictory way, it is not possible to look at changing interest rates and draw conclusions about the direction of monetary policy. I suspect the reason America has never had a mini-recession (defined as unemployment rising 1% to 2% and then falling) is that our central bank has often been confused about the relationship between interest rates and monetary policy. When the economy entered a minor recession, the Fed initially made matters worse by tightening monetary policy, triggering a larger recession. They wrongly assume that they will not tighten policy because they lower their target interest rate. But lower interest rates don’t make it easier to make money – especially if the natural rate of interest falls even faster.

Suppose central banks gradually become aware of this mistake. If my hypothesis is correct, the US should next experience mini-recessions. These will happen instead of normal recessions because the Fed will no longer be fooled by an obsession with interest rates. The Fed will increase its focus on a wide variety of financial market indicators, and will also be more willing to take a “whatever it takes” approach to broaden market expectations of future aggregate demand (NGDP). ) to stabilize.

It would take decades of improved performance to be sure it wasn’t just luck, so I won’t be around to see if my prediction comes true. In fact, I’m not even sure the Fed is starting to see past the misconception that interest rates are monetary policy, a necessary condition for better performance. It is also possible that they can reduce the severity of the business cycle through another policy reform, for example by introducing level targeting.

I estimate there is a greater than 50% chance that we are entering our first mini-recession. If so, I think it is likely that this period will not be labeled a “recession” by the NBER. In that case it would be our very first soft landing. And closely related to these points, this would be our first violation of “Sahm’s Rule.”

Alternatively, we could have a full-blown recession. Either way, the next twelve months will likely be much more interesting than the last twelve months. Here are my (very unscientific) guesses:

1. Boom: Unemployment peaks at 4.3% – 5% chance

2. Mini recession: unemployment peaks between 4.4% and 5.3% – 65% chance

3. Recession: Unemployment rises above 5.4% – 30% chance

I’m curious what readers expect. Feel free to add anything in the comments section. As a side note, these are my definitions; the NBER uses several criteria to define recessions. I define a soft landing as at least three years of sustained expansion without causing high inflation, even after unemployment is near a cyclical low. We’ve never done that before. That would be a much more impressive national goal than a repeat of the 1969 moon landing in the 2030s.

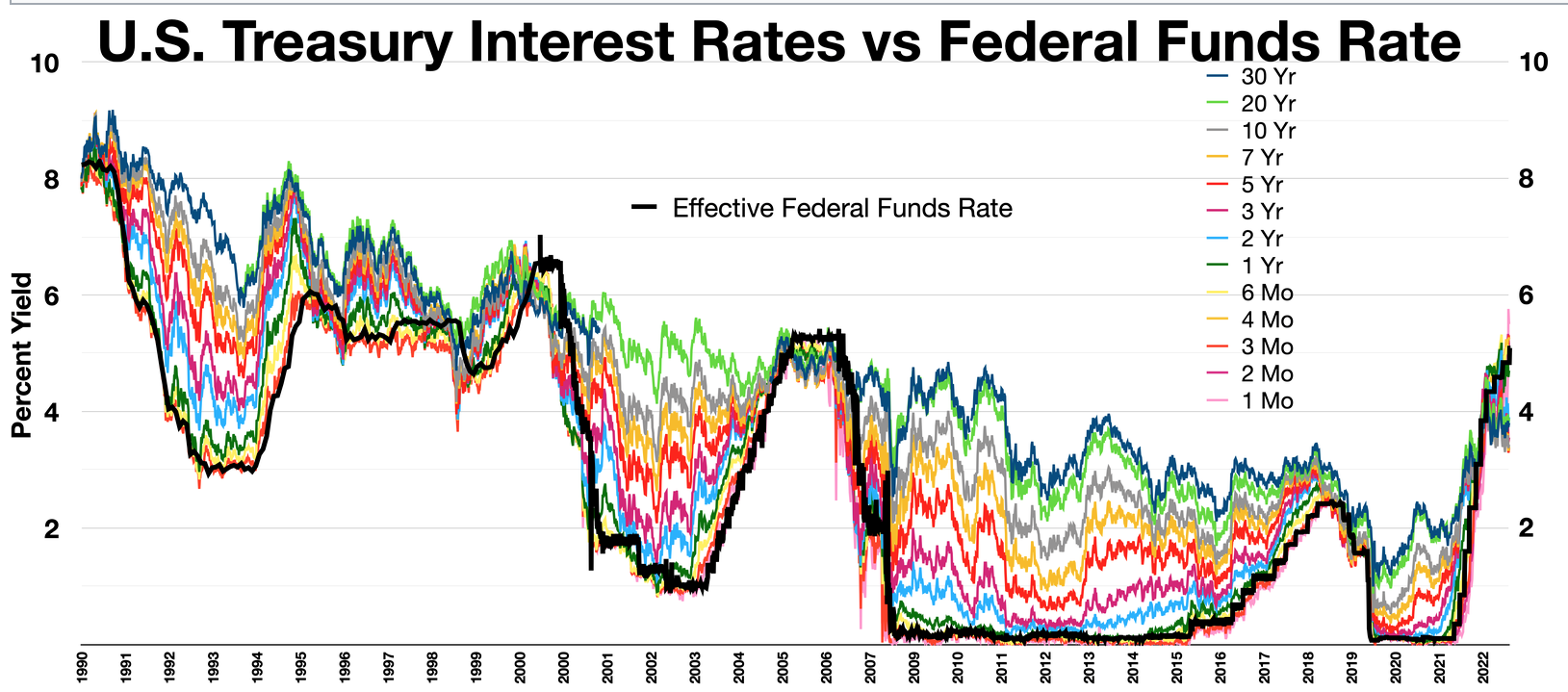

P.S. This is a cool graph: