Health

Scientists learn how neighborhood can influence cancer biology

WLiving here has a relationship with your chances of getting cancer and surviving cancer. Epidemiologists studying this connection they see in the data have focused on so-called social determinants of health — poor access to transportation, for example, could make it harder for residents to see a doctor. Places without supermarkets with fresh food can mean poorer nutrition for locals.

The worse outcomes for people from poorer, more stressful neighborhoods suggest that our physical and social spaces are somehow affecting our biology, says Brittany Jenkins-Lord, a molecular biologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Medicine. “Historically, this has been done in epidemiological ways, looking at risk factors and associating them with mortality or different types of outcomes,” she said. But how exactly something like a neighborhood might influence cancer biology is part of a growing area of research for scientists like her, Jenkins-Lord said. By investigating things like tumor genetics, epigenetics, modifiers of gene expression, and other biological markers, they are starting to yield intriguing results.

“Neighborhoods can influence the expression of genes in this way and that could influence cancer outcomes,” Jenkins said. “Making that leap is intuitive, but we don’t have the data to do that. we haven’t had social determinants data yet and linked it to biology. That’s where we are now as a field.”

Neighborhoods are like ecosystems in their complexity, with countless variables, both small and large, that can plausibly influence health and biology. For example, the built environment, whether it has sidewalks, parks or polluting factories, and an area’s crime statistics can affect how easy it is for residents to exercise or spend time outdoors. “We think about work hours and how that affects when people can see a doctor, diet and the food system,” said Hari Iyer, an epidemiologist at the Rutgers Cancer Institute who studies neighborhoods. “It’s difficult to collect everything. Neighborhood is a good proxy for all these things.”

Scientists try to get a rough idea of the advantages and disadvantages a neighborhood can offer through something called a ‘deprivation index’. These measure things like the average wealth and income, education level, unemployment level and occupations of the residents in a census. They also measure housing quality in the census tract by things like the percentage of homes with incomplete plumbing or that are owner-occupied.

In recent years, several studies have found that residents living in neighborhoods with greater disadvantage, based on one or more of these indexes, also appear to have concerning changes in the biology of their tumors. In the latest of these studies, published last month in JAMA network openedResearchers from the University of Maryland and Virginia Commonwealth University looked at the expression of certain stress-related genes in the prostate tumor cells of 218 men from Baltimore. Of the participants, 77% were black and the rest were white.

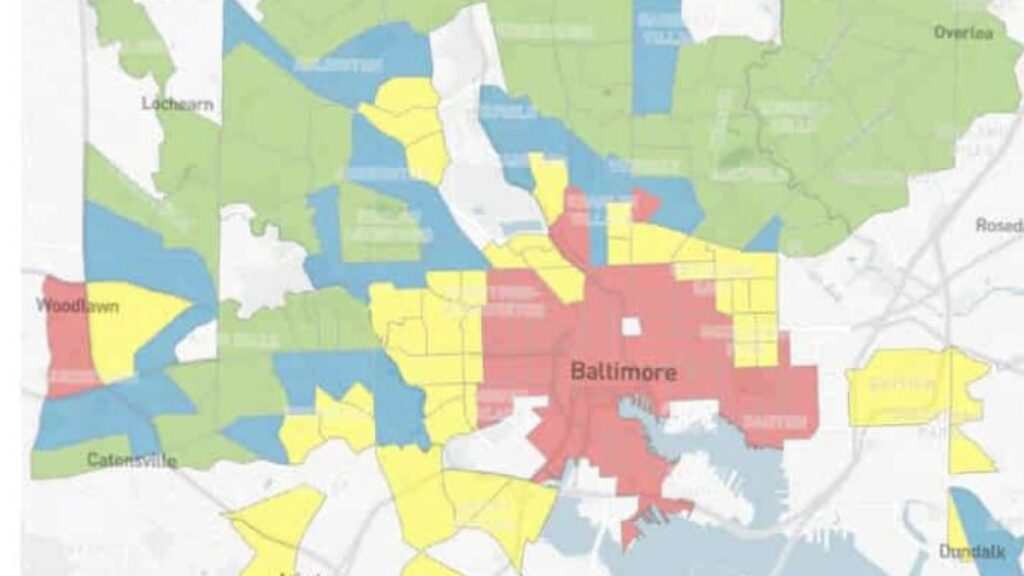

These researchers then looked at participants’ neighborhoods based on three different indexes and whether they lived in a historically defined area, a systematic and often race-based denial of investment in specific neighborhoods that became common in the 1930s. Across these indexes, men living in areas of greater poverty had slightly higher activation of stress- and inflammation-related genes than those living in areas of lower poverty. The same was true for men who lived in a historically defined area and for those who did not.

That means it’s possible that living in worse neighborhoods could have had an effect on these men’s prostate cancers, says Kathryn Barry, a cancer epidemiologist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and senior author of the paper. “The role of chronic stress resulting from living in deprived areas, which may have downstream biological consequences, such as increased inflammation, and which could lead to an increased risk of aggressive prostate cancer,” she said.

Other recent studies have revealed similar signs that the neighborhood you live in could change the biology of cancer. Work Jenkins-Lord from Johns Hopkins, published last year, also found that increased neighborhood disadvantage was associated with epigenetic changes and reduced expression of key genes in breast cancer. “Women from areas of high deprivation had changes in two tumor suppressor genes. Lower expression of these gene suppressors is associated with poorer survival, so much so that they can help predict who will survive and who will not,” she said.

Like other researchers, Jenkins-Lord found that African American race was strongly correlated with neighborhood poverty. The contribution of ancestry could confound the results of these neighborhood studies, Jenkins-Lord said. “It is difficult to find out whether ancestry-specific variants can alter the expression of tumor suppressors,” she said. “Is it the environment? Is it genetics? Is it both and which contributes more? We still have more work to do in that area.”

Or it could also be an indicator that certain racial disparities in cancer outcomes, such as the fact that black men are more than twice as likely to die from prostate cancer and that black women are more than 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than white people, could be partly due to neighborhood factors. “We will say that black people have worse outcomes because of their biology. Maybe. But maybe it’s not really their biology, but the breed is based on historical issues and societal structures, where we don’t have access to care,” said Robert Winn, director of the Massey Cancer Center at Virginia Commonwealth University.

The fact that science is moving toward discovering signals associated with neighborhoods within tumors is a strength, Rutgers’ Iyer said. “It’s not like you’re trying to make a claim based on stress markers in the blood,” he said. ‘No, it is in the tumor and is correlated with the environment. It helps us get closer to the argument, like, hey, your stress can have a major impact on your cancer and its progression.

It’s also science that researchers hope will inform community and neighborhood policies and public health interventions, Iyer said. Such research can reveal which neighborhood factors have the greatest influence on the outcomes. In work After finishing with the Veterans Affairs health care system, he found that racial disparities in prostate cancer were much smaller among veterans compared to those in the general population, even if they came from the same neighborhood. “For us, that was a pretty strong argument that you can do a lot by improving access to care,” says Iyer.

This work to determine the relationship between social determinants of health and cancer outcomes is just beginning, said Massey’s Winn, who calls the emerging field the science of connecting the dots between “DNA and ZNA” or zip code near the association. “This creates molecular responses to access to care, molecular responses to where you live and the food you have access to, and missing the one bus that takes you where you need to go,” Winn said. “This is a superficial comment. We are still in the early stages of the bare skin and the sharp knife.”