Finance

US job growth has been revised down to the highest level since 2009. Why is this time different?

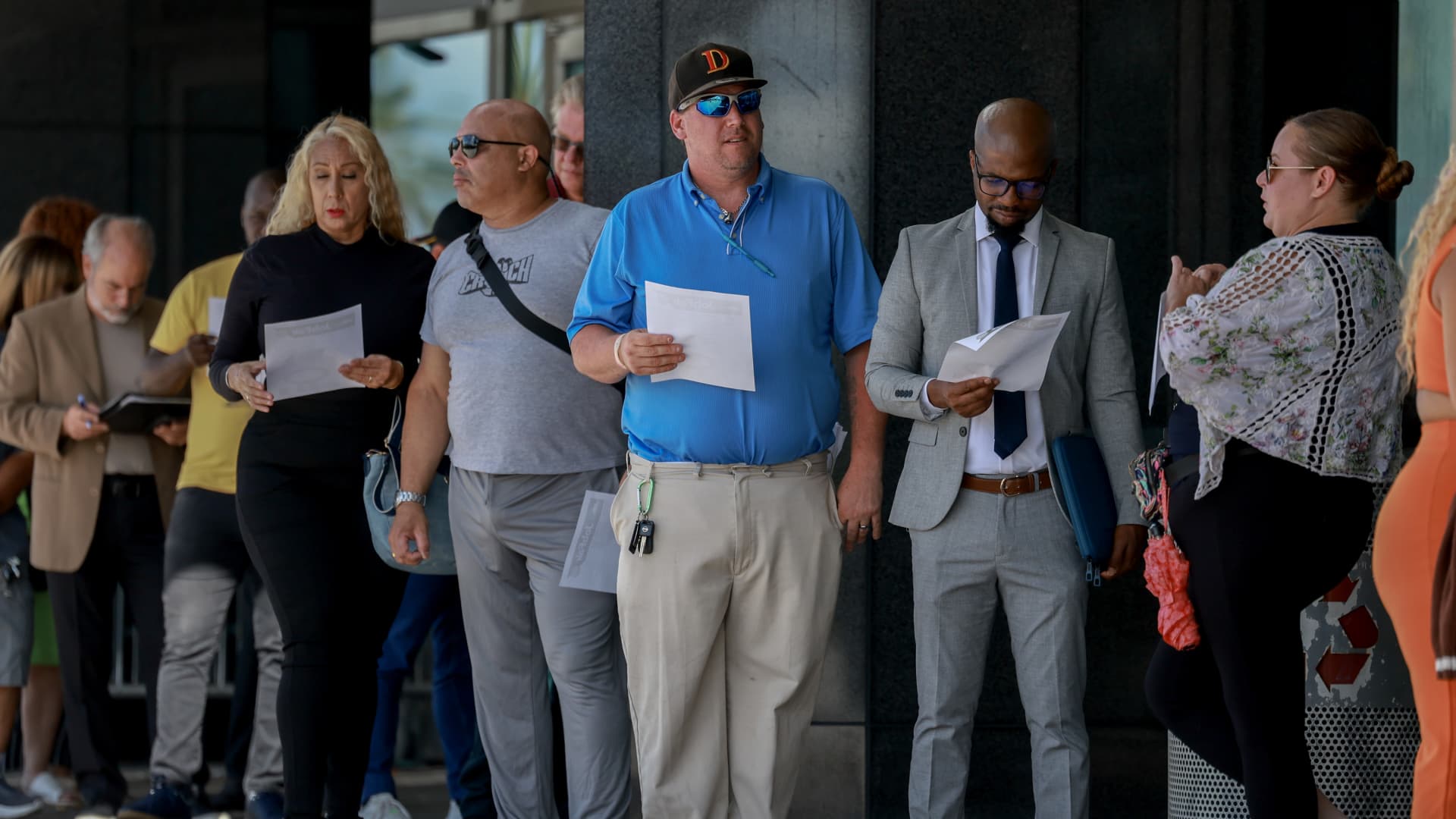

People line up as they wait for the opening of the JobNewsUSA.com South Florida Job Fair at Amerant Bank Arena on June 26, 2024 in Sunrise, Florida.

Joe Raedle | Getty Images

There is much debate about how many signals we should take from the 818,000 downward revisions to US payrolls – the largest since 2009. Is this a sign of recession?

A few facts worth considering:

- By the time the 2009 revisions came out (824,000 jobs were overestimated), the National Bureau of Economic Research had already declared a recession six months earlier.

- Unemployment claims, a concurrent data source, had risen above 650,000, and the insured unemployment rate had peaked at 5% that same month.

- GDP as reported at the time had been negative for four quarters in a row. (It would subsequently be revised higher in the two of those quarters, one of which was revised higher to indicate growth rather than contraction. But economic weakness was generally evident in the GDP figures, the ISMs and numerous of other data.)

The current revisions cover the period from April 2023 to March, so we don’t know if the current figures are higher or lower. It may well be that the models used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics are overstating economic strength at a time of increasing weakness. While there are signs of a weakening in the labor market and economy, which this could well be further evidence of, here is how those same 2009 indicators are behaving now:

- No recession has been declared.

- The four-week rolling average of 235,000 unemployment claims is unchanged from a year ago. The insured unemployment rate of 1.2% has remained unchanged since March 2023. Both are a fraction of what they were during the 2009 recession.

- Reported GDP has been positive for eight consecutive quarters. It would have been positive for even longer if there had not been an irregularity in the data for two quarters in early 2022.

As a signal of deep weakness in the economy, this major revision is for the time being an outlier compared to the figures from that time. As a signal that job growth during the review period has been overestimated by an average of 68,000 per month, this is more or less accurate.

But that only reduces average employment growth from 242,000 to 174,000. How the BLS will distribute this weakness over the twelve-month period will help determine whether the revisions were more concentrated toward the end of the period, meaning they are more relevant to the current situation.

If that’s the case, it’s possible the Fed didn’t raise rates that high. If the weakness continues after the period of revisions, it is possible that the Fed’s policy is now simpler. This is especially true if, as some economists expect, productivity rates rise because the same level of GDP appears to have been achieved with less work.

But the inflation numbers are what they are, and the Fed reacted more to those numbers than to jobs numbers during the period in question (and now).

So the revisions could modestly increase the likelihood of a 50 basis point rate cut in September, for a Fed that was already inclined to cut in September. From a risk management perspective, the data may increase concerns that the labor market is weakening faster than previously thought. During the austerity process, the Fed will monitor growth and employment rates more closely, just as it has monitored inflation rates more closely during the rate hike process. But the Fed will likely give more weight to current unemployment claims, business surveys and GDP data than to the backward-looking revisions. It’s worth noting that over the past 21 years, revisions have been in the same direction only 43% of the time. This means that in 57% of cases a negative revision is followed by a positive revision the following year, and vice versa.

The data agencies make mistakes, sometimes big ones. They often come back and correct them, even if it is three months before the election.

In fact, economists at Goldman Sachs said later Wednesday that they think the BLS may have overestimated the revisions by as much as half a million. Unauthorized immigrants who are not now in the unemployment system but were initially listed as employees were responsible for some of the discrepancy, along with a general tendency to overstate the initial revision, the Wall Street firm said.

Employment data may be subject to noise due to immigrant recruitment and may be volatile. But there is a huge set of macroeconomic data that, if the economy were to plummet like it did in 2009, it would show signs of that. That is not the case at the moment.