Finance

Goods, services and tariffs – Econlib

Over a long period of time, the US economy has shifted from goods to services. If the US moves to a high tariff policy, it would accelerate the shift to services. To see why, we need to look at some basic concepts from trading theory.

To illustrate some ideas, I would consider a 20% tax on all imported goods. Services are assumed to be exempt. Let’s start with the example of imported oil. For simplicity, we will assume that the US imports most of its oil (an assumption that is no longer valid).

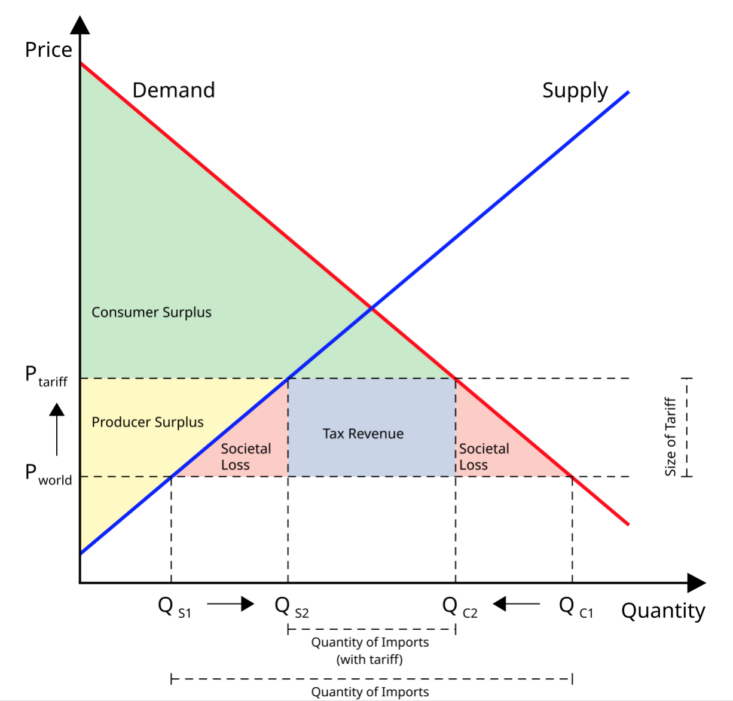

If the world oil price were $80 per barrel, a 20% tax would increase the price by $16. However, the price would likely increase by just under $16 because the tariff would stimulate domestic production and discourage domestic consumption. So $16 would be the upper limit of the resulting price increase. That equates to about 40 cents per gallon. I suspect the actual increase will be slightly smaller, say about 37 cents, which is roughly double the 18.4 cent federal tax on gasoline.

Today the US is a major oil producer. We still import a lot of oil, but we also export a significant amount. In that case, the net effect of the tariff is more complex. Some of the oil currently exported could be used for domestic consumption in parts of the US that currently import oil. In that case, the biggest effect could be higher transportation costs as the oil is diverted.

Most economists assume that rates are paid by consumers in the domestic economy. In principle, some of the burden could be borne by foreign exporters if the tariff had the effect of reducing the global price of the imported good. On the other hand, if other countries retaliate with their own tariffs (which seems plausible), then it again makes sense to assume that virtually all tariffs will be borne by domestic consumers. I think that’s the most reasonable assumption.

Is a rate of 20% the same as a VAT of 20%? Not entirely, because VAT applies to both goods and services, while a rate only applies to goods.

Does a rate improve the current account balance? Probably not, since the current account balance consists of domestic savings minus domestic investment. In most cases, the current account balance would increase only if it stimulated domestic savings, which would only happen if tariff revenues were used for deficit reduction. And even in that unlikely case, the effect would be quite small. The most important effect of tariffs is reduction all trade in goodsboth import and export. With a high tariff policy, both our imports and our exports would become smaller. Most importantly, the goods sector of the economy would be taxed at a much higher rate than the services sector, reducing the share of goods in GDP.

This may seem counterintuitive, because we tend to think of tariffs leading to more production of goods that were previously imported. And they do. But the negative effects on goods production are even greater. This is because the positive effect of fewer imports on domestic production is offset by the negative effect of fewer exports. But tariffs also cause consumption to shift from goods to services. It is this additional effect (outside the trade balance) that causes the economy to shift from the production of goods to the production of services.

Would a 20% rate increase inflation? That depends on the Fed’s response. It is likely that the Fed would allow a one-time price increase because the effect of the rates is “transitory.” If the Fed wanted to avoid higher prices, they would be forced to implement a tight monetary policy that lowers nominal wages. Either way, tariffs tend to reduce after-tax real wages unless they are offset by tax cuts elsewhere.

A high tariff on imported oil would discourage oil consumption, something many environmentalists support. I leave it to the reader to determine whether this is the goal of most proponents of a high-tariff policy.

P.S. Obviously the world is complex and you can make assumptions that produce different results. But I suspect that many people don’t understand that the first-order effects predicted by standard trade models are that tariffs will stimulate the production of services and reduce the production of goods.

Here is the simple trade graph in the special case where the importing country has no influence on the world price: