Technology

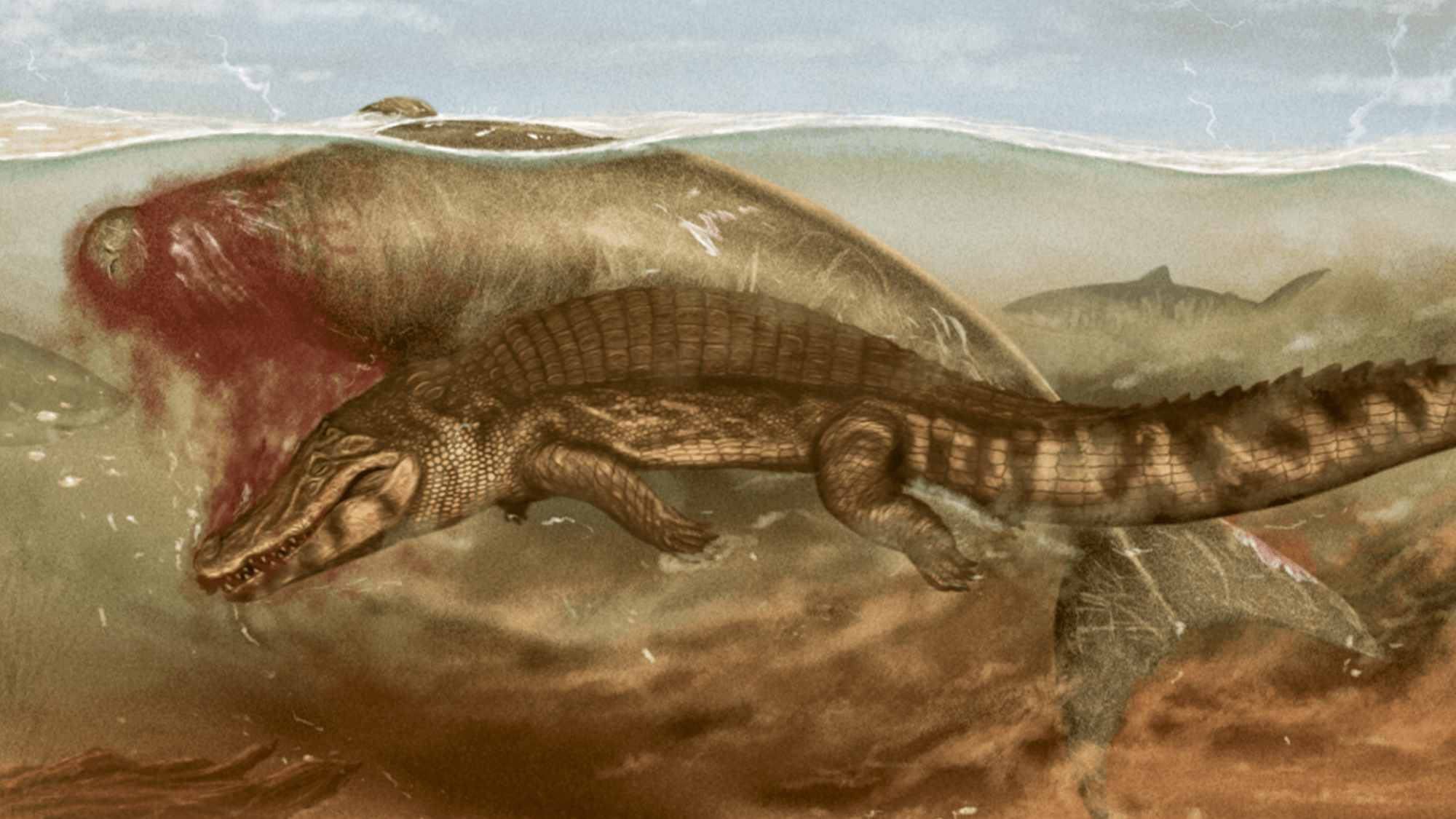

Crocodile attacks manatee. Tiger shark plucks manatee apart.

On an unknown day, millions of years ago, a relative of a prehistoric manatee was attacked by a hungry crocodile. After it was killed by the crocodile, the manatee’s remains were scavenged by a tiger shark. This prehistoric food chain anecdote is based on new fossil evidence described in a study published on August 29 in the Journal of vertebrate paleontology. The findings suggest some similarities between the key players in the Miocene food chain and those living on Earth today.

Prey, predator and scavenger

Scientists have found other evidence in the fossil record that animals ate each other, which could tell them a lot about where organisms belonged in prehistoric food chains. The mighty megalodon snacked on the snouts of sperm whales and may even have competed with great white sharks for resources. About 508 million years ago, Tokummia katalepsis captured soft prey with claws that worked like can openers.

In this new studya team of paleontologists digging in what is now northwestern Venezuela found the fossilized skull of a dugong manatee from the extinct genus Culebatherium. The fossil dates from about 23 million to 11.6 million years in the early to middle period Miocene epoch.

[Related: Meet the extinct sea cow that cultivated Pacific kelp forests.]

Some “striking” deep tooth impacts, aimed at the manatee’s snout, suggest that the crocodile first tried to grab its prey by snout to suffocate it. Two other large incisions indicate that the crocodile then likely performed a “death roll” while holding the manatee. This behavior still exists commonly observed in modern crocodiles.

Furthermore, the team found the tiger shark tooth in the manatee’s neck. There were also shark bite marks on the entire skeleton, which the team said shows how the remains were picked apart by the scavengers. Modern tiger sharks are also known scavengers that will eat almost anything.

“Today, when we observe a predator in the wild, we find the carcass of prey that also demonstrates its function as a food source for other animals; but fossils of these are rarer,” Aldo Benites-Palomino, co-author and paleontologist from the University of Zurich in Switzerland, said in a statement. “We weren’t sure which animals would serve this purpose as a food source for multiple predators. Us previous research has identified sperm whales eaten by several shark species, and this new research highlights the importance of manatees within the food chain.”

Although evidence of predator-prey interactions can be found in the fossil record, these usually take the form of broken fossils with markings the meaning of which is not entirely clear. This makes distinguishing signatures of active predation and scavenging events challenging, Benites-Palomino said.

“Our findings represent one of the few papers documenting multiple predators on one prey, and as such provide a glimpse into the food chain networks in this region during the Miocene,” says Benites-Palomino.

A ‘paleontological rescue operation’

The international team of scientists found the fossil in outcrops of the Early to middle Miocene Agua Clara Formationsouth of the city of Coro, Venezuela. The remains include a fragmentary skeleton with a partial skull and eighteen associated vertebrae. Preserving the fossils cortical layer– which defined how the brain’s gray matter was structured – also helped them observe detailed evidence of prehistoric predation.

Study co-author and University of Zurich paleobiologist Marcelo R. Sanchez-Villagra called the discovery “remarkable,” in part because it was found 60 miles away from other fossils and how they found it.

[Related: This tiger-sized, saber-toothed, rhino-skinned predator thrived before the ‘Great Dying.’]

“We first heard about the place through word of mouth from a local farmer who had noticed some unusual ‘rocks’. Intrigued, we decided to investigate,” said Sanchez-Villagra said in a statement. “Initially we were not familiar with the geology of the site, and the first fossils we dug up were parts of skulls. It took us some time to determine what they were: manatee remains, which look quite strange.

The team consulted geological maps of the areas and examined the sediments in this new area. That helped them determine the age of the rocks in which these fossils were uncovered. It took several site visits to fully excavate the remains, as these were relatively extensive animal remains.

“After locating the fossil site, our team organized a paleontological rescue operation, using extraction techniques with full enclosure protection,” said Sanchez-Villagra. “The operation took about seven hours, during which a team of five people worked on the fossil. The subsequent preparation took several months, especially the painstaking work of preparing and restoring the cranial elements.”