Health

According to researchers, the bird flu virus is transmitted to mice through milk

With the spread of the bird flu virus among dairy cows in the United States, researchers have done just that … [+]

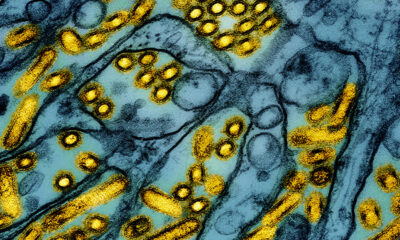

Untreated milk containing the bird flu virus H5N1 can cause disease in mice, according to researchers a study published Friday. The scientists also reported that the infectious virus remains detectable in raw milk for up to five weeks. In addition, heat treatment of milk significantly reduces the concentration of the infectious virus, but does not eliminate it.

Since March, federal, state and local officials have been monitoring the spread of bird flu among livestock in the United States. The virus has so far been detected in 58 herds in nine states, according to data provided by US Department of Agriculture. The first reported transmission of this virus from livestock to humans took place in April. A second suspected case of livestock-to-human transmission was The CDC reported this on Wednesday. Both cases likely occurred from direct contact between the person and an infected animal. Although the virus has been found in milk from infected dairy cows, the risk of transmission through milk has not yet been fully investigated.

To investigate this risk, virologists studied contaminated milk samples from a dairy cow herd in New Mexico. Sequence analysis of the viruses present in the milk confirmed that they were HPAI H5N1 viruses closely related to the virus previously linked to a human infection in Texas.

To determine whether contaminated milk could transmit the virus, the researchers experimentally orally inoculated mice with 50 microliters, or about a drop, of milk. They observed the mice for four days and then euthanized them. The researchers noted that all mice survived the four days, but began showing some signs of illness, such as lethargy, a day after the inoculation.

Researchers measured the amount of virus in various organs after the mice were euthanized. They found high levels of virus in the lungs and trachea. They also discovered viruses in other organs, including the liver, kidneys, spleen and mammary glands.

To investigate the stability of the virus in milk, the researchers took two approaches. First, they checked over time for the presence of the virus in milk stored at 4 degrees Celsius, or about 39 degrees Fahrenheit. After five weeks, the amount of infectious virus in the samples decreased, but only slightly. In other words, the virus remains present when milk is cooled.

Second, they examined the effects of heat treatment on the virus in milk. Contaminated milk samples were incubated at 63 degrees C (approximately 145 degrees F) for various periods of time ranging from 5 to 30 minutes. After these incubations, no infectious virus could be detected in the milk. Alternatively, milk samples were incubated at 72 degrees C (about 161 degrees F) for 5 to 20 seconds. After these incubations, the amount of infectious virus was significantly reduced, but not eliminated.

What do these studies tell us? There are three important conclusions from this report. First, the H5N1 avian flu virus can be transmitted to mammals by mouth through contaminated milk. Secondly, the virus remains stable for a longer period of time in untreated milk if the milk is kept refrigerated. Third, heat treatment of milk reduces, but does not eliminate, the infectious virus.

But there are some important caveats. The mouse transmission studies were conducted in a specific type of mice (6-week-old female Balb/cJ mice). This degree of standardization is typical of scientific experiments. However, it does raise the question to what extent the results are generalizable. Based on these experiments, we cannot confirm that people who drink H5N1-contaminated milk will become ill. The heat inactivation studies are also very informative, but may not be generalizable. As the report authors note, “benchtop experiments are not a summary of commercial pasteurization processes.”

We know that the bird flu virus H5N1 can be detected in milk. We now have evidence that contaminated milk can cause disease in mammals. Current evidence suggests that pasteurization effectively eliminates infectious viruses from milk. But the potential impact of this virus on dairy cows and humans remains a major concern.