Health

Ambitious federal study has failed to reduce opioid overdose deaths

IIn 2019, amid a worsening drug crisis, the federal government launched a study with an ambitious goal: to reduce opioid overdoses in participating communities by 40% through evidence-based interventions such as naloxone distribution and providing access to addiction medications.

But communities that implemented the public health strategies did not see a statistically significant reduction in opioid overdose deaths, according to data published Sunday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Given the simple premise of the study – that helping communities use proven strategies can help prevent deaths – the results came as a surprise. But leaders are warning against making too much of the disappointing data, citing the rapidly changing drug supply and, crucially, the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“We started this investigation in January 2020, and guess what happened in March 2020?” Redonna Chandler, National Institute on Drug Abuse official who led the research project. “And while our communities continued to work in the background, we couldn’t reach the hospitals. We couldn’t get into jail. We weren’t able to get to many of the places and spaces where we wanted to implement our evidence-based practices.”

According to the NEJM analysis, of the hundreds of individual interventions that communities had planned as part of the study, only 38% had been implemented by the beginning of the year in which the data was analyzed.

The National Institutes of Health launched the initiative, known as the HEALing Communities Study — short for Helping End Addiction Long-term — in April 2018. It awarded $344 million to participating communities, using funds appropriated by Congress the year before assigned for substance use research. .

“Now is the time to channel the efforts of the scientific community to find effective – and sustainable – solutions to this formidable public health challenge,” said several top NIH officials, including then-Director Francis Collins and NIDA -director Nora Volkow, wrote in 2018 when the project started.

The study focused on 67 communities in Massachusetts, New York, Kentucky and Ohio. About half were chosen to implement their overdose prevention strategies starting in 2020; the rest implemented their strategies from 2022, after the comparison period between the two groups.

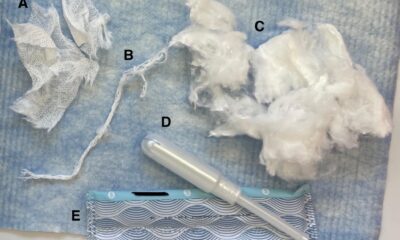

Interventions include increasing access to medications such as methadone and buprenorphine by reducing restrictions, supporting health care providers, and working with jails and prisons. It also included education about opioid prescribing and increasing distribution of naloxone, a drug used to reverse opioid overdoses.

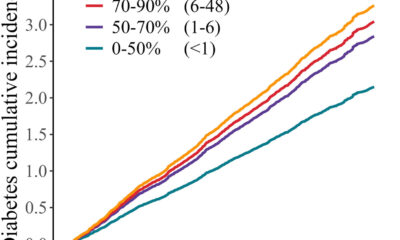

During the comparison period, communities that previously implemented their strategies experienced 47.2 opioid-related overdose deaths per 100,000 people; communities that had not yet started experienced 51.7. However, despite an almost 10% lower mortality rate in communities that had implemented their strategies, the results were not statistically significant.

In statements, federal health officials called the study at least a partial victory. While the interventions have not meaningfully reduced overdose deaths, officials argued, they have paved the way for future action and created a framework to help hard-hit communities adopt and begin implementing new policy approaches, in the hope that with more time and without Covid-19, the number of deaths would drop.

Volkow, the director of NIDA, said the increasing use of stimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine, and the proliferation of fentanyl, mean society must “continue to develop new tools and approaches” to prevent overdose deaths. Miriam Delphin-Rittmon, the administrator of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, said the investigation “recognizes that there is no quick fix.”

And in an interview, Chandler, the study’s director, emphasized that the results should not call into question what research has long shown: There is a “mountain of evidence,” she said, supporting the belief that drugs like naloxone , medications for opioid use disorder and safer prescribing techniques save lives. According to Chandler, the challenge lies in the implementation – not in the strategies themselves.

The study published Sunday, she said, “in no way negates the evidence suggesting the strengths of these interventions.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health conditions is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Us financial supporters are not involved in decisions about our journalism.