Health

An outdated Medicare rule is harming dementia patients with anxiety

MMemory loss is the most obvious symptom of Alzheimer’s disease. But for the more than 6.5 million Americans who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease—and the people who support them—memory problems are often the least of their problems. Many people with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia also experience mood and behavioral symptoms ranging from anxiety and depression to violent outbursts and psychosis.

Family members, caregivers, and even some medical providers often dismiss these so-called neuropsychiatric symptoms as manifestations of behavior over which the individual has control. While these symptoms can be very disruptive and overwhelming, they are not the individual’s fault or an extension of their personality; they are another manifestation of the disease.

The assumption that people with dementia can control these behaviors has led to a widespread misunderstanding that often results in social stigma, such as that associated with other mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety. And that stigma keeps many people with Alzheimer’s disease and their families from seeking professional help. For those who do seek help, red tape often prevents doctors from prescribing medications that can effectively treat their neuropsychiatric symptoms.

As a nurse and director of a comprehensive dementia care practice, I work every day to help people with dementia and their families cope not only with memory loss, but also the neuropsychiatric symptoms that come with it.

Far too many of them suffer in silence. That’s a shame, because these symptoms can often be alleviated with the right approach.

When physicians have the opportunity to evaluate their patients’ symptoms, they can identify appropriate treatment strategies and help healthcare providers implement them. For example, many people with dementia and their families can manage symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and inappropriate behavior by establishing a predictable daily schedule, engaging the person in meaningful activities, and creating a calm and comforting living environment.

In other situations, an individual’s neuropsychiatric symptoms are severe enough to warrant medication. In 2023, the FDA approved the first drug specifically for people with Alzheimer’s disease who need help controlling agitation. Other antipsychotic medications, such as olanzapine, can also help relieve these symptoms.

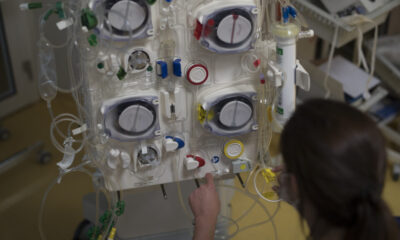

Yet outdated regulations often prevent these drugs from reaching the people who need them. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which determines coverage for their beneficiaries and influences other insurance plans, has created policies that make it more difficult for providers to prescribe antipsychotics when necessary. These restrictions make it particularly difficult for individuals moving into long-term care facilities, where providers may find that they are no longer allowed to administer the medications the person needed while living at home.

It is a widespread and growing problem, especially because people with dementia who experience mood swings, violent behavior, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms are four times more likely to be sent to a long-term care facility or institutionalized—and feel to be in the place that is least likely. to treat their symptoms.

CMS’s restrictions are based on good intentions: wanting to monitor how physicians use certain medications in institutional settings. But policies should never prevent a healthcare professional from providing the most appropriate care for their patient’s unique symptoms and medical needs.

A medical provider would never leave a tumor or broken bone untreated, so why do we leave dementia patients’ symptoms untreated? Everyone deserves high-quality, effective and judgment-free care. It is time for CMS to eliminate policies that undermine this goal.

Carolyn Clevenger, a gerontological nurse, is the founder and director of the Integrated Memory Care practice at Emory University.