Health

Black vets could receive higher VA benefits if the breed is not used in the lung test

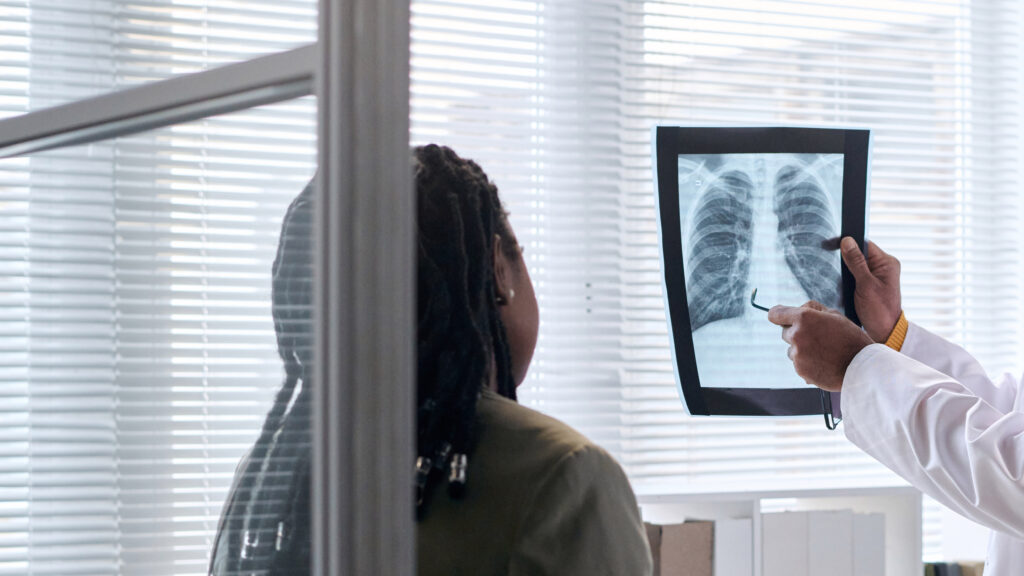

RRemoving a patient’s race from an equation used to assess lung function — a change that health equity advocates are calling for — would mean that the lung disease of nearly half a million Black Americans would be reclassified as more serious, and that black veterans could get more. than $1 billion in additional disability benefits, according to a study published Sunday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The issue of how race is used in clinical algorithms has become a topic of widespread debate and controversy in recent years, and the American Thoracic Society is one of several medical societies grappling with the issue. Last year it was said that a racial correction could contribute to health disparities in lung disease should no longer be usedbut there were calls for more research into the downstream effect of such changes.

The new paper, presented at the association’s annual meeting in San Diego, is an attempt to quantify those effects.

The study’s lead author, Raj Manrai, an assistant professor of biomedical informatics at Harvard Medical School, said he hoped the results would help prepare doctors and health care systems for the large number of patients whose lung disease status could change if result of new varieties. free comparisons. Pulmonary function laboratories in hospitals, the authors said, may need to build more capacity and be prepared for a possible increase in the number of patients as more patients require follow-up lung tests.

Nirav Bhakta, a pulmonologist at the University of California, San Francisco and lead author of the thoracic society statement, called the new study “an enormous effort” and said it paints the clearest picture yet of the changes affecting health care systems can expect as a result of using the new equations. He told STAT that other data indicated that additional testing and imaging was warranted to prevent mortality and that lung function labs could respond by adding capacity and also reducing unnecessary lung tests “which have not yet been proven to change outcomes.”

Remote home spirometry using AI-driven quality control and coaching could also ease the burden on hospital laboratories, he said.

Boston Medical Center, a safety-net hospital serving a diverse and international patient population, recently updated its spirometers to use the race-neutral equation. The change will require software updates and integration into electronic health records, but BMC was fortunate to be in the middle of an update and thus incurred few additional costs, said Michael Ieong, an assistant professor at Boston University who directs the pulmonary function testing laboratory the hospital.

Ieong said it would take some time to see how many patients are actually affected and that the mix of patients seen by a hospital system would likely play a role. He noted that Johns Hopkins physicians reported that they have been using the race-neutral equation for more than a year, with little change in patient volume.

The article makes clear, he said, that “the use of simple cutoffs by non-medical entities (such as those assessing disability claims or making hiring decisions) needs to be urgently reassessed.”

The racial correction was used to adjust the measurements of spirometers, devices used to assess lung function and diagnose and treat respiratory diseases. This adjustment – by as much as 15% in black patients – has been questioned for decades by health care equity advocates because it dates back to slavery-era science, which was used to justify slavery by suggesting that black people had to work to keep their supposedly weaker lungs healthy. The adjustments were also criticized because categorizing people as black for medical reasons is problematic, as race is not a biological category and many black Americans have significant European ancestry.

“We found profound clinical, financial, and occupational implications of the way race is operationalized in lung function testing,” the study’s lead author, fourth-year Harvard Medical School student James Diao, said in a statement. The authors used data from almost 370,000 patients in five data sets and calculated lung function using both the old and new equations. They found that the race-specific and race-neutral equations performed similarly in predicting lung disease symptoms, health care use, and death, but resulted in large differences in how lung disease was classified in terms of severity.

“Black patients previously assessed for pulmonary function impairment should strongly consider being reevaluated using the new race-free equations, especially if they have been specifically assessed for disability or workers’ compensation,” because they could qualify for substantially higher disability benefits. says Rohan Khazanchi, a co-author who is an internist and pediatrician in Boston and a research affiliate at Harvard University’s FXB Center for Health & Human Rights.

“The downstream disparities in disability and workers’ compensation reflect a unique example of racism in medicine, as it can exacerbate the enormous racial wealth gap that already exists and continues to exist in our country,” he added.

All told, the authors say, 12.5 million Americans could see reclassifications in their lung function impairment levels. For example, the study found that an additional 430,000 black people would be diagnosed with moderate to severe COPD, while 1.1 million fewer white patients would be diagnosed.

Veterans Administration disability benefits could increase by 17% overall for black veterans — with increases of nearly $2,000 to $10,000 per year for many vets — and could decrease by 1.15% for white veterans. The change could result in a total redistribution of $1.94 billion per year to more than 400,000 eligible veterans.

The study “forces us to reconsider how eligibility is determined for disability or occupational fitness. For too long, such provisions have been based on simple measures,” two pulmonologists, Meredith McCormack and David A. Kaminsky, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “We need new approaches that apply equally to everyone.”

The results, the study authors say, will lead to trade-offs. Some patients with more severe disease may qualify for new treatments, benefits and breathing support, but lose eligibility for other treatments, such as surgery to remove lung tumors.

The comparison could also influence people’s suitability for certain jobs that require healthy lungs. Under the new equation, more than 750,000 Black Americans would no longer be eligible for fire service jobs, while 1.27 million white Americans would be newly eligible.

“Ultimately, we hope that clinical decision support tools can serve all patients in an evidence-based manner,” Khazanchi said. “Our study helps reinforce this point by demonstrating no significant differences in accuracy between race-based and race-free lung function comparisons.”