Health

Bone marrow donors don’t have to be a perfect match in cancer care: study

aAs a hematologist-oncologist in Miami, Mikkael Sekeres always hopes his patients will find the perfect match for the bone marrow transplant they need to save their lives — but he doesn’t expect that. Most of his patients are Latino or African American, and the number of perfect matches is much lower among racial or ethnic minorities.

That bleak picture could soon change. This is evident from a study published on Wednesday in the Journal of Clinical Oncology found that certain unmatched donors, or people whose bone marrow is not as similar to the patient’s, produced similar results as matched donors, as long as patients received a key drug called cyclophosphamide to prevent dangerous complications. That suggests that patients in need of a transplant can safely consider both matched and single matched donors, vastly expanding the pool of potentially acceptable donors for all patients, but especially for those of African, Latino or Asian descent.

“For most of my patients it is much more difficult to find a match. It has become the norm to look at people who are not donors and who are not a perfect match for my patients,” said Sekeres, chief of hematology at the University of Miami Sylvester Cancer Center and who did not participate in the study. “That is why this study really appealed to me. The classic teaching is that you want a perfect match, as opposed to less than perfect. What this study suggests is that if you take the right medications after transplant, it may not be that big of a problem.”

If so, up to about 84% of African American patients could have a potential donor on the national registry. Currently, less than 30% of African American patients have a potential match in the NMDP registry, formerly called the National Marrow Donor Program.

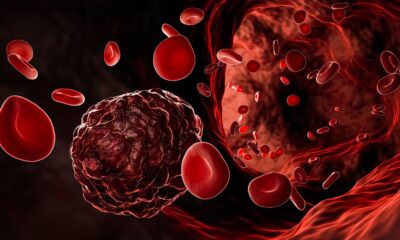

Bone marrow transplants, also called hematopoietic cell or blood stem cell transplants, are essentially transplants of the immune system and often represent a patient’s last chance at a cure for blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma. Oncologists first give chemotherapy to put the cancer into remission, but the chemotherapy also causes significant damage to the healthy bone marrow, where the stem cells that give rise to blood and immune cells are located. The transplanted immune system would then replenish the lost stem cells and attack any remaining cancer in the patient.

The problem is that the transplanted immune system can also reject its new home and attack healthy tissues in a potentially fatal complication known as graft versus host disease. Your own immune system avoids this by using a system of proteins called HLAs, or human leukocyte antigens. Each cell carries these proteins like a security badge, identifying itself as part of your own body to patrolling immune cells. A matched donor would therefore carry the same eight key HLA markers as the recipient – or be an eight-of-eight match – making it more likely that the transplanted immune system will settle into the new host without much fuss.

“For years it was known that having a donor whose immune system is matched to yours provided a better outcome. When I was a fellow, the results were dismal when patients received an unmatched donor,” said Brian Shaffer, a bone marrow transplant physician at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the study’s lead author.

Several years ago, scientists at Johns Hopkins University showed that cyclophosphamide could reduce the risk of these complications in half-matched first-degree relative donors. Blood stem cells are resistant to this specific chemotherapy, but not so much immune cells such as T and B cells that cause graft-versus-host disease. These immune cells are particularly vulnerable to the toxin when they are activated and in the process of multiplying, Shaffer said.

This means that when the transplanted immune system invades the patient, some of these T and B cells will recognize that they are in the wrong body and lash out against the recipient, but in doing so make themselves more vulnerable to cyclophosphamide. That means the drug can selectively remove the immune cells most likely to cause dangerous complications.

“Other T cells will remain silent because they are happy with the host,” Shaffer said. “These angry T cells start dividing and become more exposed to cyclophosphamide.”

Some of the first indications that this strategy would work to alleviate even unrelated and unmatched immune systems in patients came in 2021. A team of researchers saw no significant difference in the overall survival of about 80 patients who received a matched or a matched, unrelated transplant after one year. This study extends these findings with data collected from approximately 10,000 patients treated for acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

The study was possible in part because so many patients, especially those of non-European ancestry, cannot find an 8/8 match in the registry. So their only option is to go to a mismatched donor of 7/8 or lower. Some centers were already using cyclophosphamide to prevent graft-versus-host disease, while others are using a different drug, a calcineurin inhibitor. Shaffer and colleagues collected data from 153 centers comparing patients who received an 8/8 or 7/8 match and cyclophosphamide or a calcineurin inhibitor.

“The key finding is that patients who received post-transplant cyclophosphamide had no differences in survival or any other major clinical outcome, freedom from graft-versus-host disease and other complications, from matched or unmatched donors,” Shaffer said . This did not apply to patients who received calcineurin inhibitors. These patients also had worse survival, relapse, and graft-versus-host disease compared with those who received cyclophosphamide.

“I was happy to read this article,” said Warren Fingrut, a transplant and cell therapy physician and MD Anderson Cancer Center who did not participate in the study. “By increasing access to seven of eight mismatched, unrelated donors, many more patients, especially those from racial, ethnic minority groups, will receive a transplant.”

Although the study focused specifically on patients with acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes, the findings are of “great importance for patients with other hematological malignancies and non-malignant conditions who are also undergoing transplants,” Fingrut said. Although, he added, it may still be important to replicate the work in other indications.

According to the analysis, broadening the pool of bone marrow donors by 7/8 mismatched transplants increases the potential match rate for Asians and Hispanics from less than 50% to nearly 90%. The potential match rate for African Americans increases to 84%. The potential match rate for white Americans also increases from about 79% to 99%.

Those are huge gains and would likely help substantially reduce health disparities in these cancers, Fingrut said, although it wouldn’t solve all the disparities in access to transplants. One problem is that even if there is a potential donor on the registry for a patient, many of these donors are present can’t actually donate. This may be because their contact information has changed and is unreachable, because they have new health conditions that prevent them from donating, or because they may no longer be interested.

“About half of the donors in total are not available for confirmatory typing. If you zoom in on African descent, less than a third is available,” says Fingrut. “That is not improving over time, and it is not solely due to the Covid-19 pandemic.”

This study opens a way around that problem, Fingrut said. Transplant physicians might consider 7/8 unmatched donors in addition to matched donors for patients who have a poorer chance of finding a match in the registry. “If you look for the few unrelated donors who never show up, and only then switch to mismatched donors or alternatives like cord blood donors, it actually impacts overall survival,” Fingrut said. “These patients cannot wait months for a donor who never comes.”

Moving back to a match of four, five, or six out of eight would further increase the match rate for all patients to nearly 100%, although it is still unclear whether using more highly mismatched donors would worsen outcomes. “Everyone is eagerly awaiting that data,” says Fingrut.

But there is also another way to improve the match rate without resorting to donors who are no longer a match, he pointed out. More people could do that join the donor register.