Health

Brain-Machine interfaces lead to discussions about ethics. 4 areas of focus

Philosophy study as learning about the moral and ethical concept of small persons. Traditionally historical … [+]

As we move into a new era of technology integration, questions will arise about privacy and ethics surrounding certain technologies. For months I have been discussing the rapidly advancing field of brain-machine interfaces. Rapidly growing technology allows integration between our minds and external technological devices, theoretically enabling a more accessible world for those who could benefit from such technologies.

However, many of these devices rely on a direct or indirect electrical connection to the brain. The natural implication is that a number of questions arise. Is my brain data being stored and shared without my knowledge? Will my brain data be used against me in a future situation? Or more dystopian? How do I know my thoughts are my own when I’m connected to a computer?

The study of the ethics of the brain-machine interface will emerge soon after the technology itself takes over, similar to the way sociologists now study the impact of social media, smartphone use, and so on. We need to express these concerns head-on and be prepared for these conversations when they arise, rather than ignoring them until they become a problem.

There are at least four concerns regarding the ethics of the brain-machine interface, but there are likely many more.

First, there is the sensitive nature of the data collected by brain-machine interfaces. These gadgets have access to a person’s innermost thoughts, emotional state and mental health. Due to the sensitive nature of this personal information, it should be transmitted and handled with caution to avoid the possibility of unauthorized access or misuse.

Many large companies appear to collect and store personal data without the express consent of the users of their products. It seems likely that such a situation could arise in a future where brain-machine interfaces are widely adopted, although the personal data could be much more intimate.

In particular, the state of Colorado has taken an important step by introducing privacy regulations for the use of commercial neurotechnology devices.

Second, there is the possibility of discrimination and exploitation. Brain-machine interface data can reveal information about a person’s truthfulness, psychological traits, and attitudes, which can lead to workplace discrimination or other unethical practices.

Imagine going into a job interview fully prepared and confident in your chances. Yet the employer reveals that they did a background check, which revealed that personal information had been collected through your brain machine interface device. Privacy quickly disappears when your private thoughts are no longer private.

Third, there are concerns about hacking and third-party audit risks. The risk of brain-machine interfaces being hacked and controlled by malicious actors is increased due to wireless communications. If this were to happen, it could result in the retrieval of private information or tampering with the device, which could harm the user.

In the United States alone, there are more than 800,000 cyber attacks every year. Typically, hackers break into private accounts, such as emails, gain access to more sensitive information, such as banking passwords, and extort the individual or steal their money. Similar attacks could occur with brain-machine interfaces.

Fourth, there is a need for more legal protection. While existing laws such as HIPAA and GDPR provide some privacy safeguards, it is still being determined whether they will adequately address the unique privacy challenges posed by the volume and sensitivity of data generated by advanced brain-machine interfaces. It will be necessary to update these laws to include specific workplace and personal protections for when data breaches between the brain and the machine interface inevitably occur.

These are questions that we will have to answer sooner or later. These technologies are becoming increasingly sophisticated in the United States and could quickly reach public markets on a large scale on the global stage. Recent reports suggest that the Chinese government is working with biotech companies in the country to rapidly promote the production of brain-machine interfaces to integrate cognitive improvements into its vast population.

The report notes that China is more interested in non-invasive brain-machine interfaces than invasive versions, which may be a reasonable guide to mitigating some of the potential ethical concerns.

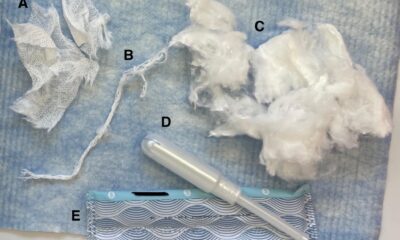

Wearable technologies could be equipped with more hardware and software protection than an implant placed directly on the skull. While implants create more robust brain data, wearable technology is developing rapidly. For example, ultrasound and electrography technologies are viable candidates for accurate brain imaging.

You can divide users of brain-machine interfaces into two main groups: those with serious conditions or physical disabilities who require invasive brain-machine interfaces, and those without who are likely to use non-invasive versions.

We implore those developing these machines to ensure that both groups are as protected as possible from potential ethical exploitation. It is imperative that the general public trusts that their personal information is just that: personal for the long-term adoption of these technologies.

This story is part of a series about current advances in regenerative medicine. This piece reviews advances in brain-machine interfaces.

In 1999, I defined regenerative medicine as the set of interventions that restore normal function to tissues and organs damaged by disease, injured by trauma, or worn down by time. I include a full spectrum of chemical, gene and protein-based medicines, cell-based therapies and biomechanical interventions that achieve that goal.

If you would like to read more of this series, please visit www.williamhaseltine.com.