Health

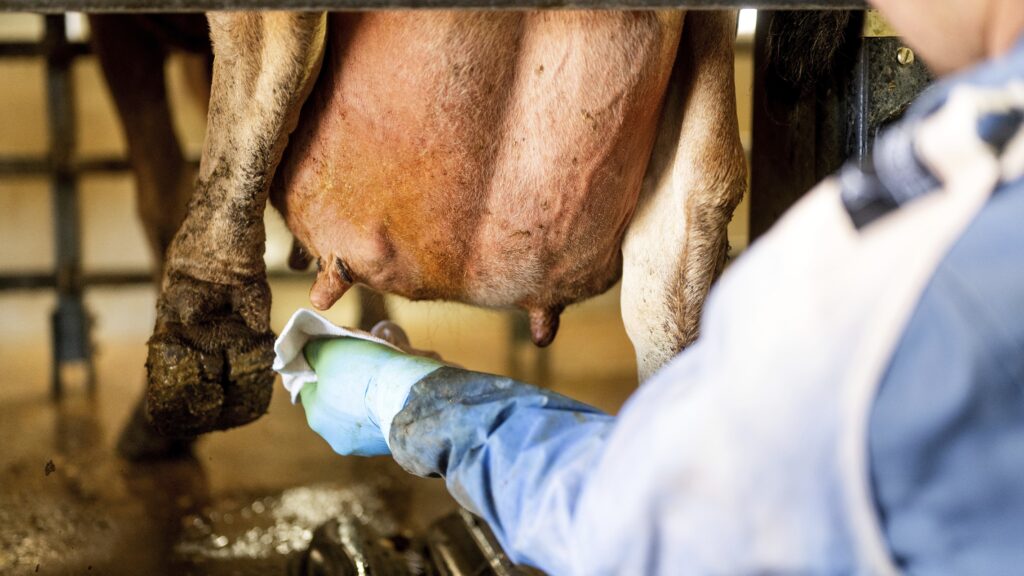

California, the country’s largest milk producer, will test three herds for the H5N1 bird flu

On Thursday, the California Department of Food and Agriculture announced it is investigating the possible introduction of H5N1 bird flu into cattle at three Central Valley dairy farms. If confirmed, these would be the first known cases in that state.

In a statement, Officials said testing of samples from the three farms is currently underway at the state veterinary diagnostic laboratory. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has not yet confirmed the outbreaks. If confirmed, California would become the 14th state to report an infection of H5N1 in dairy cows.

California, the nation’s largest milk producer, is home to approximately 1.7 million dairy cows. Nearly 90% of them live in the San Joaquin Valley, a vast tract of fertile farmland that stretches more than 250 miles from Stockton to Bakersfield. Dairy farms there often have large holdings separated by significant distances, and farmers have been for months take extra precautions such as bleaching cow trailers to reduce cross-contamination.

Workers there typically handle only one flock, unlike Colorado and Michigan, where workers sometimes work shifts both on dairy farms and nearby poultry farms, creating additional biosecurity challenges. In both states, where outbreaks have reached double digits, infections on dairy farms have spread to poultry farms, genetic analyzes of the virus show.

But despite these measures, many feared that, given the lackluster national response to the outbreak, the H5N1 virus would sooner or later strike California. “It seemed like it was only a matter of time,” said Terry Lehenbauer, a bovine disease epidemiologist and professor emeritus at the University of California, Davis.

If confirmed, California would become the first new state since Wyoming announced on June 7 that the virus had been found in one herd. Last month, Oklahoma confirmed the presence of the virus in two herds, but samples from those animals were collected as early as April. and were only put up for testing after the USDA began offering farmers financial compensation for lost milk production in early July.

The program is part of an $824 million USDA effort to strengthen broader testing and surveillance for avian flu on dairy farms, which also includes a voluntary pilot program for farms to proactively test samples from bulk milk tanks on a weekly basis. If herds show no sign of H5N1 for three weeks, farmers participating in the pilots can freely transport their livestock across state lines without having to test individual animals.

But both programs have seen limited adoption by the dairy industry. Only from Wednesday 33 herds were regularly monitored nationally as part of the USDA pilot program, including one herd in California.

A CDFA spokesperson did not respond to STAT’s questions about how many tests California has conducted since the U.S. outbreak began in late March, or how the three farms were identified.

“Ultimately it all comes down to the number of herds tested,” says Lehenbauer. “Not as many tests have been done as we would like from a scientific or medical perspective.”

Colorado, which currently leads the nation in most reported herds, is also the only state to do so has mandated all dairy farms submit milk samples from their bulk tanks for testing on a weekly basis. In the weeks after that order went into effect on July 22, another 11 infected herds were discovered through bulk milk tank testing. The program allowed officials there to get a more accurate picture of how the virus is spreading and give farmers early warning so they can isolate animals before the infection spreads through their entire herd.

In unpublished research, scientists from Colorado State University and Iowa State University who tested samples from bulk milk tanks found that the virus is detectable for 14 to 16 days before farms saw a significant increase in symptoms, such as low appetite, lethargy, fever and a drop in milk production . production.

Therefore, the most important time for testing is the two to three weeks before clinical signs appear, says Keith Poulsen, professor of large animal internal medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. “By the time you see them, there’s nothing you can do about them.”

But so far, no other state has followed Colorado’s lead. Since June, Iowa has implemented a more limited surveillance protocol, requiring dairy farms within 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) of an infected poultry farm to submit samples from bulk tanks and sick animals for testing on a weekly basis. Along with Minnesota and Wisconsin, Iowa also requires testing of lactating cattle before showing them at state and county fairs.

Elsewhere, and outside of these circumstances, states largely leave the decision to test up to farmers. And a coordinated effort to implement mandatory surveillance at the national level has yet to materialize.

“We have been told that we have had to carry out large-scale surveillance by testing bulk milk tanks several times since May.” Poulsen said. “For some reason it never happened.”

A USDA spokesperson told STAT via email that the network of veterinary diagnostic laboratories authorized to test for H5N1 was being evaluated to ensure there was sufficient capacity to handle an increase in voluntary surveillance testing , but that there is currently no plan for government-mandated bulk milk. tank testing at national level.

Decisions on whether to require bulk milk testing “ultimately rest with each individual state,” the spokesperson said, adding that the agency appreciates Colorado’s order because it allows the USDA to better understand where the virus is and “to take additional steps to protect animal health. as well as farmers, farm workers and their communities.”

But Poulsen said the lack of a coordinated effort to expand that type of testing nationwide is a missed public health opportunity, for both animal and human health. “We’ve built a system that can respond to these types of contagious outbreaks, but we’re not really using it,” he said. “It’s mind-boggling.”