Health

Coercive Sterilizations Revealed by STAT Provocative Outrage

FFederal officials, medical organizations and reproductive health advocacy groups have expressed outrage in response to STAT’s recent survey, which found that women with sickle cell disease felt pressured into sterilizations as recently as 2017 and 2022.

Some said they were aware of other contemporary cases of tubal ligations with questionable consent – in people with severe disabilities, for example, or in situations where patients did not understand that the procedure should be considered permanent – and said the reporting of STAT revealed a new dimension. this disturbing pattern. For many, it also demonstrated the need for improvements in access to care, reproductive counseling, physician and patient education, and federal sterilization policies.

“For too long, racial inequality and underrepresentation in our health care system have contributed to adverse health outcomes for Black women in the United States. Before making important life decisions, every woman deserves to be fully informed about her reproductive health options – anything less is unacceptable,” said U.S. Rep. Robin Kelly (D-Ill.), chair of the Congressional Black Caucus Health Braintrust.

In a statement, the American Medical Association said it “strongly opposes the practice of non-consensual medical procedures, including forced sterilizations of any kind, and has established clear guidelines and policies to protect and ensure the rights of patients ensuring that clear communication promotes informed patient decisions about their needs.” concern.”

Of the 50 women with sickle cell disease interviewed so far for STAT’s Coercive Care study, seven described feeling pushed toward tubal ligations or hysterectomies that they weren’t sure they wanted or about. they weren’t given enough information — and patient advocates and doctors said they had heard directly about dozens of other cases. The pattern extends to at least seven states, with surgeries performed by several gynecologists, who often view it as a way to protect mothers from the increased risks of pregnancy complications associated with sickle cell disease, patients said. About 100,00 Americans live with the disease, about 90% of whom are black.

Some of the sterilizations in STAT’s reporting were covered by Medicaid, which entailed reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which is under the umbrella of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. An HHS spokesperson said, “Every woman should have the right to make fully informed choices about their own bodies, medical decisions and families,” adding that “CMS is committed to ensuring that facilities certified as Medicare and Medicaid provider compliance with quality standards and acts when it receives information that a facility may not be in compliance.”

The agency declined to comment further on whether it is considering any policy changes to prevent such situations from occurring in the future.

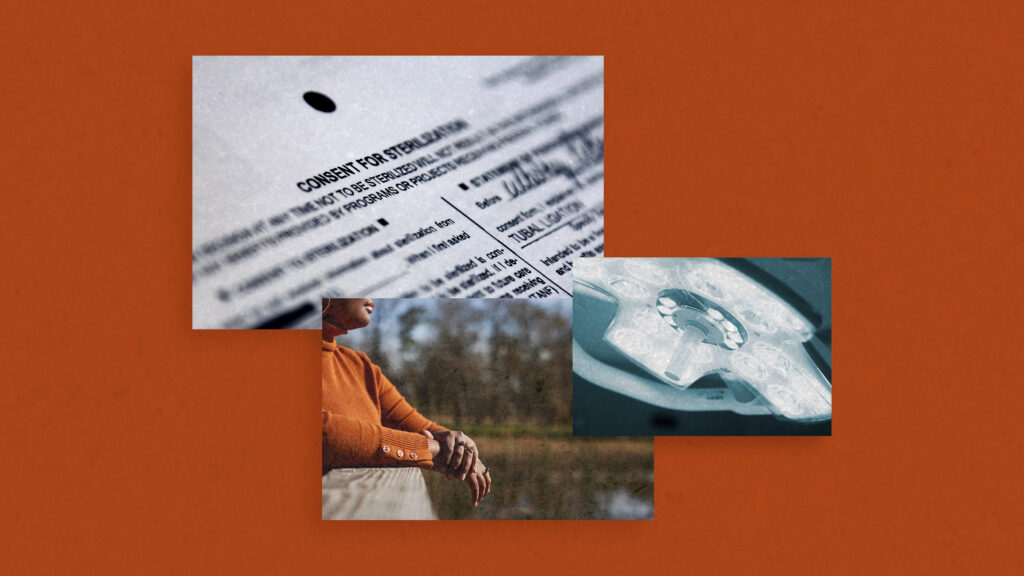

Kate McEvoy, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, suggested that this “could be a matter of standard practice, as opposed to a matter of policy,” and pointed out that there are federal rules designed to protect public insurance recipients against forced sterilization, including a specific consent form that must be signed at least 30 days before the procedure and a provision that the patient must be at least 21 years old and competent.

For many, however, these cases of sterilization with questionable consent raise questions about how well that policy works. As Megan Kavanaugh, a principal investigator at the Guttmacher Institute, put it: “These types of coercive practices run counter to reproductive justice and are an example of why systems like the Medicaid form of sterilization must be rebuilt and reimagined through the lens of sexual and reproductive health equity.”

For example, researchers have pointed out that the form can be difficult for patients to understand, among other criticisms. HHS declined to comment when asked about these issues.

“It is so unfortunate that any health care provider would impose their beliefs and discriminatory attitudes on a patient and take away someone’s reproductive capabilities,” said Yolanda Lawson, a gynecologist in an independent practice in Dallas and president of the National Medical Medical Association. Association, representing African American physicians.

She added that patients came to her who did not understand that the tubal ligation they received from another doctor should have been considered permanent, and they asked for her help in conceiving. On the other hand, Lawson also pointed out that post-sterilization regret is common and can play an important role in some cases where a doctor’s words seem coercive in retrospect. That’s part of the reason she checks in with her patients on three separate occasions, to make sure sterilization is what they actually want and that they fully understand the procedure.

“If you have even the slightest doubt, I wouldn’t recommend going ahead with sterilization,” she said.

Ma’ayan Anafi, senior advisor for health equity and justice at the National Women’s Law Center, said these stories from the sickle cell community are “horrifying and disturbing, but unfortunately not surprising.” Although eugenics has seemingly become less popular, the stories on which it was based never really disappeared; they just evolved.”

Between the 1920s and 1970s, some 70,000 Americans, many of whom were poor, disabled, or people of color, were forcibly sterilized because they were considered “unfit” and their reproduction was seen as a threat to society. According to Anafi, 31 states, plus Washington DC, still legally allow the forced sterilization of people with certain types of disabilities. Those laws are not old: some were only passed in 2019. It is difficult to know how often these cases occur, Anafi continued, because they usually require a court order and the cases in question are often closed.

Part of the solution, advocates say, is education: better sex education, so people have a better understanding of the variety of contraceptive options; better medical education so that doctors are better trained to conduct these consent conversations; and better history education so that people understand the medical abuses of the past and how they continue to shape the present.

“I had never heard of this,” Miroslava Chavez-Garcia, a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said of forced sterilizations of sickle cell patients. Chavez-Garcia heads the California Eugenics Legacies Project, which aims to increase public awareness of these issues. “It certainly reflects long-standing practices and beliefs about who is fit to reproduce.”

Alison Whelan, chief academic officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, said doctors in training are learning the skills involved in discussing informed consent. “Pressing patients into unwanted sterilizations is unacceptable,” she said, emphasizing that communication between doctor and patient is critical to good care. “Medical students learn the critical competencies of communication and bedside manners in medical school, and each school designs its own curriculum to teach these core skills.”

Another important element is improving access to good care and information. “Patients could be better informed that pregnancy with sickle cell disease carries significant risks for mother and baby, even with good medical care,” said Lewis Hsu, director of the pediatric sickle cell program at the University of Illinois at Chicago. These decisions can be difficult, he continued, and for him the best solution is to have time to make a “Reproductive life plan,” come up with strategies on how best to ensure a safe pregnancy if one is desired, and how to avoid it if it is not.

Some point out that new gene therapies for sickle cell disease may bring the sterilization debate into question, but such therapies bring their own questions about reproductive freedom: Because they involve drugs that can harm a person’s ability to have a child, some patients must choose between a possible cure and fulfilling their reproductive dreams, because fertility preservation is not always covered by insurance.

“It is unacceptable that reproductive health choices are being taken away from women with sickle cell disease (SCD). SCD is a complex and serious disease that requires coordinated and comprehensive treatment, especially during pregnancy – from prenatal care and management of complications to birth. No woman should ever be denied a voice in her own health care decisions,” said Mohandas Narla, president of the American Society of Hematology.

“Equality in healthcare is not a buzzword. It is a promise that cannot be fulfilled without also paying attention to patient autonomy, including reproductive autonomy. Whether patients are considering abortion care, breast cancer screening, gender-affirming care, or any form of contraception – including sterilization – they should be able to do so freely and of their own volition,” said Kersha Deibel, senior advisor for Black health equity. at the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.