Sports

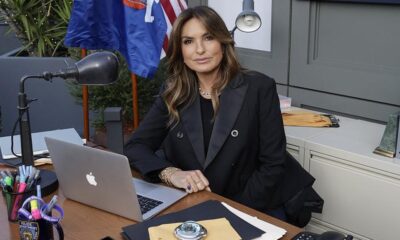

Darryl Strawberry wanted to quit baseball at the age of 19. These two Mets brought him back

To this day, 43 years later, Darryl Strawberry still has a nickname for his 1981 season with the Class A Lynchburg Mets.

“I call it,” Strawberry said on the phone last week, “suck season.”

At the time, suckling season was the most challenging of Strawberry’s life. It was the season he faced his first failures on the baseball diamond. It was the season in which he first heard racist comments from the stands. It was the season he came so close to quitting baseball and hanging up his jersey for good.

And so when Strawberry’s No. 18 is retired on June 1 at Citi Field, it’s only fitting that among his honored guests will be the two people who helped him through the down season: manager Gene Dusan and teammate Lloyd McClendon.

“Everyone looks at the success, but I look at the people who have had a big impact on me,” Strawberry said. “There is no way I would be on the field with my number retired if it wasn’t for people like them who helped me through the most challenging and difficult times at a young age.”

The first month of Strawberry’s first full season in professional ball had not gone well. Failing on the field for the first time is hard enough for any player. Strawberry had several additional spotlights on him.

The summer before, he had been the No. 1 pick out of Crenshaw High School in Los Angeles, where his coach had dubbed him “the black Ted Williams” in Sports Illustrated. His signing bonus, while not a record, was more than double that of the previous No. 1 pick.

And he was a black man playing in a southern town in Virginia. So when he was struggling on the field, he heard it from the Carolina League crowd. Home games, road games, any games – Strawberry heard the worst of it.

“They called me all kinds of names and said negative things,” Strawberry said. “You’re talking about the Deep South. I thought, ‘This is crazy.’ I grew up in Southern California and we never had to experience that growing up.

“Listen, it was 1981. Society as a whole didn’t fully embrace us – black people,” McClendon said. “They used to pass the hat to anyone who hit a home run. We hit home runs and got nothing.”

In early May, Strawberry wanted to take his bat to the stands, he said. Instead, he took his bat home.

“I just checked out,” he said. “I have indeed gone AWOL.”

“He left for a few days,” Dusan said. “It was worrying that he left. I had a feeling he would come back. I knew he would come back.”

Instead of chasing Strawberry, Dusan gave him space. He didn’t even tell Mets front office executives.

“If I did that today, they’d fire me,” he chuckled. “Everything was different in the early eighties.”

Two days later, Strawberry returned to the park, largely due to his relationship with Dusan and McClendon. Strawberry and McClendon had bonded the year before at rookie ball in Kingsport, Tennessee, when they roomed together and turned their backs on each other during their first summer in the South.

“I think we had to protect each other,” McClendon said.

Lloyd McClendon, pictured coaching the Tigers in 2019, was an important figure in Darryl Strawberry’s early professional years. (Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire via Associated Press)

And McClendon had been absent from Lynchburg at the start of the ’81 season due to a broken hand suffered in spring training. But when Strawberry left the team, that rehab period for McClendon got a lot shorter.

“When I saw him in the park I was happy,” Strawberry said, “to see a face and someone of color just like me.”

Dusan arranged for the two to room together again, even though McClendon was married.

“You have to take care of him,” McClendon recalled Dusan saying, “because he’s not going to make it if you don’t.”

“I don’t know if I was old enough to be a mentor at the time,” said McClendon, who was 22 that season, “but I was certainly a friend and a voice he could talk to. I tried to pass on the little bit of wisdom I had.”

And Dusan’s tough approach as a manager was what Strawberry needed at that moment. The day Strawberry returned to the club, Dusan was less than happy.

“I’m glad you’re back. I’m glad you’re healthy,” he told the player. “We have to get to work.”

From that day on, Dusan recalled, Strawberry became the best player he ever coached.

“He was there every day for extra strokes,” Dusan said. “Once he signed up, he was the man.”

There was a reason why Strawberry was always there for extra strokes.

“Let me put it this way: In a very good way, Gene was a pain in the ass for Darryl and me,” McClendon said. “When we were on the road, he would wake us up every morning at 8 o’clock and we would have to go to the baseball field. I think he saw something special in both of us. He certainly saw it in Darryl.

“Gene Dusan was a father figure for me that I didn’t have. He hugged me to get through some adversity early,” Strawberry said. “I became part of his family. It was just very personal to me.”

To what extent part of the family? Strawberry helped babysit Dusan’s children.

“Geno kept me going, kept me focused on not looking up and interacting with the people up there (in the stands),” Strawberry said. “That helped me a lot, because I really didn’t feel like playing there for a minute anymore.”

“He taught us so much, not just about baseball, but about life in general and how to do business,” said McClendon, who went on to officiate more than 1,100 Major League games. “You stand up, live your word and learn to be a man of honor. It was pretty cool.”

For Strawberry, suckling season remains an important part of his story. That first experience of adversity helped him through many later difficult periods, whether self-inflicted or not. It was a teaching moment, he said, one that occurred when his children wanted to give up something during a difficult time.

In ’82, playing for Dusan in Double-A Jackson, Miss., Strawberry broke through with 34 home runs, 45 stolen bases and an OPS over 1.000. Two years after the sucker season, Strawberry was the National League’s Rookie of the Year.

“I made the right decision to fight through the adversity and start believing,” Strawberry said. “I am forever grateful for that and for real people. These are real people. These aren’t people who sugar coat everything about you. But the people who showed me how to overcome.”

“It’s hard to believe,” Dusan said as he watched the teenager he managed retire his number. “I appreciate how he thinks about me. I’m proud of him.”

(Photo of Darryl Strawberry batting for the