Health

Delaware supports raw milk and downplays the risk of bird flu in raw milk

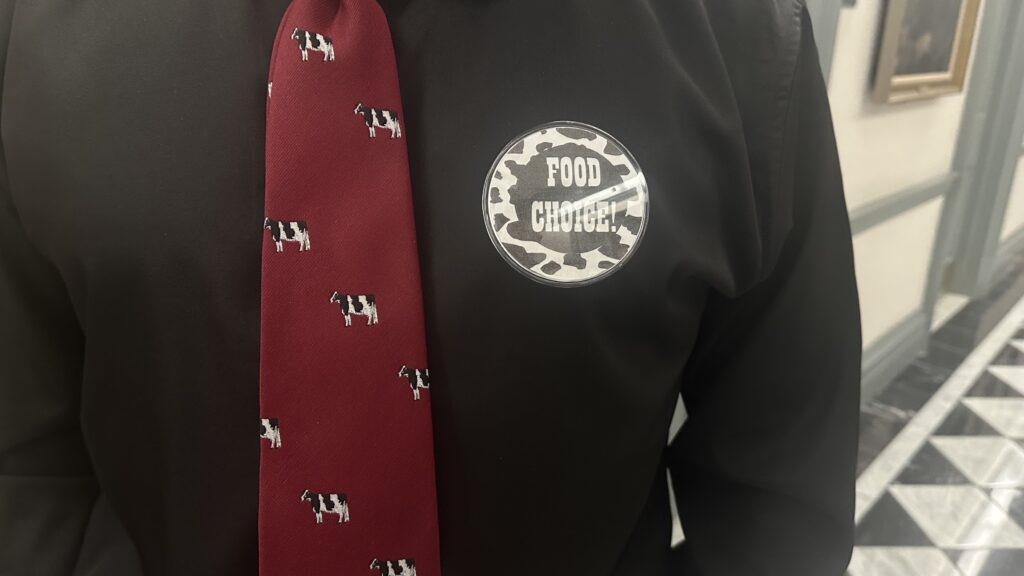

DOVER, Del. – The mood on the floor of the Delaware General Assembly was jovial last Thursday evening as lawmakers considered legislation to legalize the sale of raw milk. There were udder puns and moos. A Democratic member spoke up to ask if the Ol’ Dirty Bastard lyric “Ooh, baby, I like it raw” was written across the bill. And there was a standing ovation when the score was 39-2 after eight minutes of debate.

You wouldn’t know that raw, unpasteurized milk has exposed people to dangerous salmonella, listeria and E.coli bacteria – or that scientists are increasingly concerned that the H5N1 bird flu virus can be transmitted to humans through the product. It was never discussed.

Bird flu from raw milk is “not a problem at all,” Republican Rep. Michael Smith, the bill’s lead sponsor, told STAT before the vote.

Although there have been no confirmed cases of bird flu transmission due to the consumption of raw milk, studies have shown that animals that drank unpasteurized milk contaminated with the bird flu virus become seriously ill. Last month, the Food and Drug Administration urged state health officials to “engage regulatory authorities or, if necessary, take other action to stop the sale of raw milk, which may pose a risk to consumers.”

“You would think so [the bird flu outbreak] could slow things down a bit and perhaps at least encourage the legislature to wait and see what happens with H5N1,” said Marcus Plescia, the chief medical officer of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

Delaware’s embrace of raw milk reflects a broader nationwide skepticism toward public health warnings about its risks. Since particles of H5N1 were identified in milk earlier this year, the Louisiana legislature has also voted to legalize the drink. On-farm or retail sales are now legal in more than half the country. Sales of raw milk are reportedly increasing. Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and his vice presidential candidate have also begun publicly promoting raw milk in recent weeks.

In Delaware, that skepticism came from the highest levels of government. While Louisiana’s Secretary of Agriculture raised concerns about the health risks of raw milk during the recent legislative debate, Delaware Agriculture Secretary Michael Scuse, who was on the House floor Thursday, vocally supported the bill.

Scuse, a former U.S. Department of Agriculture official in the Obama White House, downplayed the risks of raw milk in a brief interview.

“I drank raw milk from birth until I was 11 years old, and our farms today are much better prepared – doing a much better job of milking the cattle and ensuring sanitary conditions – than they were when they were 50. 60 years ago when I was a kid,” Scuse said.

Asked about the potential for H5N1 transmission through raw milk, he said: “There is no evidence that raw milk can transmit any type of avian virus to anyone currently consuming it.” He cited a recent letter from the FDA to states to support his claim. In reality, the letter stated that regulators “do not currently know whether the HPAI H5N1 virus can be transmitted to humans through the consumption of raw milk and products made from raw milk from infected cows.” However, Scuse added that if H5N1 were found on a Delaware dairy farm “we would stop selling that milk.”

The bill’s approval by the General Assembly followed its approval by the Senate in late May. The bill now heads to the governor’s desk for final approval.

DAt first glance, elaware seems like the last place where raw milk mania would strike.

The legalization of raw milk has been branded as a conservative issue, and Delaware has not been represented by a Republican in Washington since 2011. Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state legislature by nearly 2-1. The state hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1988 — it’s home to Joe Biden, after all.

But a confluence of economic and geopolitical factors allowed raw milk to gain a foothold in the traditionally blue state.

There are only 12 dairy farms left in Delaware, according to the Department of Agriculture. Farms in the nation’s second-smallest state cannot compete with mega-farms that have sprung up in larger states like California and Texas, which now dominate dairy production.

Raw milk is, rightly or not, seen as a solution to that problem. While a small percentage of the population drinks raw milk – an estimated 4% have tried it in a recent year — those that do are willing to pay a premium. A gallon of raw milk can fetch between $10 and $12, while a pasteurized gallon costs about $4.

“It has the power to save dairy,” said Stephanie Knutson, a dairy farmer in the state who has advocated for the bill. “It has given us the opportunity to dream about a future in dairy for our children.”

Raw milk is also on store shelves in neighboring Pennsylvania, and supporters of the bill argued that legalizing it would allow Delaware to protect consumers.

“We have a percentage of people in this state that we know for sure are consuming raw milk, but it’s coming from other states, not Delaware, and we don’t know the precautions those states have in place,” Scuse said. “Let’s leave it up to Delaware to make sure it’s as safe as possible.”

Scuse and the bill’s sponsors have indicated they will require daily testing of on-farm milk for contaminants, although the bill itself — just four pages — does not spell out these requirements.

Several food safety experts told STAT that no barrage of testing will protect consumers from potentially unsafe milk — or justify passage of the bill.

“There is nothing in this bill that speaks to public health, safety and science,” said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “Actually, it’s quite the opposite.”

Nicole Martin, assistant research professor of dairy microbiology at Cornell University, said many tests that can be used often take several days to report results, which could limit their usefulness for everyday testing.

“They’re not supposed to necessarily succeed or fail,” Martin said. “They are more of a monitoring tool to detect gross contamination.”

She also noted that testing milk for pathogens typically relies on a small milk sample, meaning it cannot guarantee that the milk that ends up in consumers’ refrigerators is actually free of contaminants.

That kind of safety guarantee, according to Susan Mayne, former head of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, can only be achieved through the bogeyman in this entire debate: pasteurization.

“The beauty of pasteurization is that it can reduce/eliminate numerous pathogens at the same time,” Mayne wrote to STAT. “You can’t test your way to safe food.”

With poll after poll showing low trust in public health professionals nationally, such messages are falling apart. While raw milk advocates in Delaware say they are listening to public health officials, they argue they can safely sell the product and point to another set of numbers: The number of people who have reported getting sick from raw milk is quite low — and it number of deaths is even smaller. Between 1998 and 2018, there have been only 228 hospital admissions attributed to raw milk.

“When I looked at the CDC database … and looked at the numbers, it doesn’t support the stigma that is still there,” said Knutson, the farmer.

These statistics are almost certainly an underestimate of the actual number of people who would become ill if raw milk were widely available nationwide, since milk is currently consumed by such a small percentage of the population and it remains illegal in many states, says Marie Helweg. -Larsen, a professor at Dickinson College who is an expert on people’s perception of risk.

“These numbers seem to be a bit irrelevant,” she said. “Isn’t that like saying that very few people have died on spaceships? We haven’t really been on that many spaceships.”

Yet warnings about bird flu and raw milk are seen by many as hypothetical. Although science seems to suggest that bird flu can be transmitted through raw milk, no cases have been documented.

Don Clifton, executive director of the Delaware Farm Bureau, which supported the bill, was quick to note that the small numbers of human cases of H5N1 linked to the dairy cattle outbreak occurred in workers who came into contact with sick animals, and not among consumers of raw milk.

“I think it’s a diversion,” Clifton said. “But I’m certainly not an expert.”