Health

Do you have good health insurance? Shame. You could still get a bill for $250,000

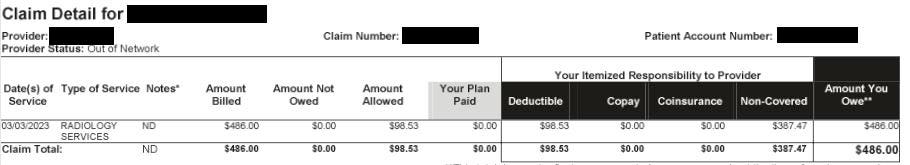

General claim for ‘radiology services’ from Jack’s insurance claim, without any other description. … [+]

Former United States Surgeon General Jerome Adams recently tweeted his disbelief that he had to pay $4,896 for an emergency room visit for dehydration after a hike — and that’s after his insurance had paid his share. If he’s struggling to understand why health care bills are so high, it doesn’t bode well for the rest of us.

As a professor of emergency medicine and health policy at the University of California, San Francisco, I have spent more than a decade researching our health care system and documenting the Wild West of hospital billing. It started when a friend in my neighborhood was hospitalized for appendicitis and received a bill for more than $53,000. He asked me what a typical charge for appendicitis was, and after doing some research, I discovered that the charges for uncomplicated appendicitis cases ranged from $1,500 to $180,000.

Such ranges are not limited to operations; even routine cases such as a normal vaginal delivery can be as low as $3,296 to as high as $37,227. These variations are common even in the most routine blood laboratories, with one hospital charging more than 100 euros $10,000 and another that charged $10 for the same cholesterol blood test.

Most of us who are fortunate enough to have insurance hope and feel protected against these absurdities. However, that is unfortunately not the case. None of us – even if we have insurance – are immune from the financially devastating consequences of the administrative monstrosity of the American health care system.

My friend Jack Emerson is an example of an educated, working, dually insured American who finds himself in exactly this situation. He has been paying into Medicare for more than forty years his entire working life, and he and his employer also pay monthly premiums for private insurance.

Post-pandemic work for him and his company had been on the back burner for years, and last March they decided to host a company-wide gathering in anticipation of the upcoming 50th anniversary celebration. While Jack was on stage preparing for a presentation, he suddenly went into cardiac arrest. Fortunately for him, the very public nature of his medical event meant he was given CPR almost immediately, and 911 took him to the Emergency Room at Kaiser Redwood City, California, where he was hospitalized for six days and amazingly survived to tell his story. Unfortunately, his release from the hospital would be the beginning of what has been ten months (and counting) of significant mental anguish and stress for him due to the financial consequences of a lack of communication between the hospital and its insurance companies.

Jack is fortunate to be covered by both Medicare Part A and employer health insurance through United Healthcare. The cost of his total hospitalization was more than $250,000. Despite repeated inquiries to Kaiser, United Healthcare and Medicare, it appears there are more than 30 outstanding claims that have not been submitted or processed in some way. As many of us who have dealt with the healthcare industry know, multiple calls from Jack to each of these entities have yielded conflicting information without any definitive action being taken.

When we take a closer look at Jack’s hospital bills, we see only the date of service, a general description such as “hospital visit,” and an even less descriptive mention of the provider (e.g., “Permanent Medical Care”). In some cases, there is a name of an actual provider, but again, no description of the service it provided other than something like “Diagnostic Services.” This is similar to us going to Safeway to buy bread, milk, and eggs, and the coupon we receive as “food.” Only in this case the costs are astronomical.

When reviewing his claim summaries, I created an Excel spreadsheet so I could view them in one place. There are 55 of these esoteric and poorly described services in categories such as “inpatient visits,” “inpatient services,” “medical services,” and “diagnostic services.” Within “inpatient services,” three of the same services are listed with the same claim number and dates of service, but billed separately as $18,323, $58,408, and $99,508. There is no further description of what these “inpatient services” entail.

Amount billed for generically labeled “inpatient services” with the same dates and claim number, but … [+]

Is this a billing error? Or costs for different services? There’s no way to know. Unfortunately, this lack of information about the statements is not specific to Kaiser; it’s just how things are done and accepted in healthcare in the United States. While the next step will be to ask for itemized bills so we can clarify what he’s actually being billed for, the entire process is exhausting, even for me as a healthcare researcher who has dedicated her career to studying these issues. Imagine the burden it would place on someone who almost died and is now recovering.

There is no other industry in the United States where we as Americans would tolerate such opacity in charges and the incompetence in dealing with them from service providers, whether hospitals or insurance companies.

How can we ensure that we, as powerless patients, do not become entangled in this administrative web of complexity? On an individual level, each of us, when receiving medical attention, could undertake an emotionally draining and time-consuming effort to obtain our itemized bills and negotiate with the hospital and insurance company (or in some cases, several). But unfortunately the chance of any success is small.

It’s time we put our collective energy into changing healthcare’s referee-free zone.

The recent policy is aimed at price transparency 90% of Americans are in favor, with examples like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Price Transparency rule and other pending bills in Congress, such as S.3548 HR 4822 and HR 410, which require cost transparency, including from insurers. There are legitimate concerns about the potential unintended consequences of price disclosure, including price gouging (of hospitals raising their prices to match competition rather than lowering them because patients cannot act as true consumers) . But while we don’t have all the answers, it is clear that the current status quo of “mystery prizes” does not serve the public.

At a larger level, more fundamental reforms are needed that address the fragmented delivery and financing of health care. This is happening across the country in numerous states. California SB770for example, was signed by Governor Gavin Newsom to begin the process of creating a single-payer financing system across the state. There are also more incremental approaches to a “public option” that allows individuals to choose a government-run plan that competes with private plans. Washington and Colorado are operational public option style programs (although using a non-traditional private insurer model), and From Nevada program will start in 2026.

While no program is perfect, we need to change the system so that we do not remain victims of an expensive and inefficient system. Additional billing and insurance costs will apply 15% of US health care spending. These costs do not translate into the delivery of health care services.

Revising our system would mean that the $350 billion We spend every year on excess billing and the insurance administration could easily take care of this $195 billion of the collective healthcare debt 41% faced by Americans.

As it stands, if Jerome and Jack can’t manage their medical bills and get them paid, we’re all screwed.