Health

Groups are urging the Biden administration to push for addiction medications

TThe Biden administration is not doing enough to ensure that people living in recovery homes have access to addiction medications like the gold standard methadone and buprenorphineaccording to a coalition of health care, harm reduction and addiction recovery groups.

The discrimination that people often face when seeking treatment with methadone or buprenorphine is especially pronounced within recovery homes, which typically provide shelter along with counseling and other social services, according to the groups. Many facilities have historically refused to admit people using addiction medications, effectively treating their use like the use of heroin or fentanyl. Although attitudes have evolved and outright bans on methadone or buprenorphine have become less common, the practice persists.

Not offering all forms of medication-assisted treatment violates both federal guidelines and the Americans with Disabilities Act, the groups wrote in a letter to Miriam Delphin-Rittmon, the director of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. They urged the agency to update its compliance practices and use all available enforcement tools to ensure beneficiaries are provided with evidence-based care.

“If you get federal funding, you have to follow federal law,” said Sally Friedman, senior vice president of legal advocacy at the Legal Action Center, a New York-based nonprofit participating in the initiative. “Prohibiting people from taking life-saving medications for opioid use disorder is discrimination – it’s that simple.”

Decades after America’s drug crisis, lawmakers, public health officials, and much of the addiction recovery community themselves have come to recognize the value of methadone and buprenorphine, medications that suppress craving and withdrawal by binding to the opioid receptors in the brain.

The drugs are highly effective: A frequently cited study from the National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that the overdose death rate among people taking methadone and buprenorphine is 59% and 38% lower, respectively, than among people not receiving the drugs.

But because methadone and buprenorphine are themselves opioids, they have long faced intense stigma from people who view them as simply trading one addictive substance for another. Although the U.S. currently experiences more than 80,000 deaths annually from opioid-related overdoses, recent data suggests that barely 1 in 5 Americans with an opioid use disorder receive treatment that includes medication.

In recent years, advocates have done just that urged to relax restrictions on both medications. Community groups ranging from churches to syringe exchange services have worked to reduce the stigma surrounding medications for opioid use disorder, as they are known, and civil rights groups and federal prosecutors have filed lawsuits to ensure incarcerated people have access to addiction medications.

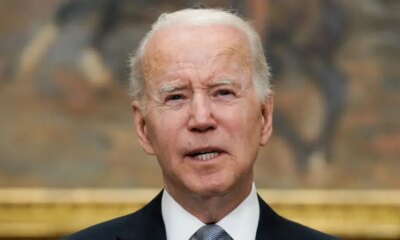

The Biden administration has also identified MOUD as a key pillar of its response to the ongoing drug crisis. In 2022, President Biden signed a new law that administrative burden removed for prescribers of buprenorphine, and earlier this year SAMHSA finalized a significant liberalization of methadone clinic regulations – the first major update to the methadone treatment system in more than twenty years.

Efforts to force recovery housing systems to comply involve major nonprofits focused on the drug crisis, such as the Legal Action Center, Vital Strategies and the Drug Policy Alliance. It also includes researchers and health care providers such as the Mayo Clinic and the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine, as well as smaller local harm reduction groups such as Philadelphia’s Savage Sisters Recovery, the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and Prevention Point Pittsburgh.

“We need to ensure that the recovery community keeps pace with the ADA,” said Toni Young, executive director of the Community Education Group, an Appalachia-based nonprofit that led the advocacy campaign. “We want SAMHSA to educate its beneficiaries. That’s the goal – not necessarily to blame them all.”

SAMHSA guidelines already require recovery housing organizations that receive grants from certain agencies to specify how they facilitate access to addiction medications. More broadly, the Department of Justice issued guidance in 2022 emphasizing that the Americans with Disabilities Act combats discrimination against people taking medications for opioid use disorder.

Much of the recovery housing community is already on board – at least in name. The National Association of Recovery Residences also warned in 2018 that categorical bans against people using MOUD would violate federal law.

However, even though the policy is on the books, the coalition behind the letter says little is being done to enforce it: As the letter states, organizations receiving SAMHSA funding can ignore the agency’s guidelines with “few repercussions” .

“Recovery housing is intended to help people recover,” said Friedman, an attorney with the Legal Action Center. ‘It should not hinder their recovery. As a federal agency, it is SAMHSA’s job to ensure this happens.”

Amid a crisis of fentanyl use, along with stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine, Young argued that banning recovery home residents from using methadone or buprenorphine is akin to encouraging relapse.

“If you’re going to say, ‘You don’t have a right to housing, and you don’t have a right to work,’ then you’re going to drive people to actively use again,” she said. “That’s a banana philosophy.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health conditions is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Us financial supporters are not involved in decisions about our journalism.