Health

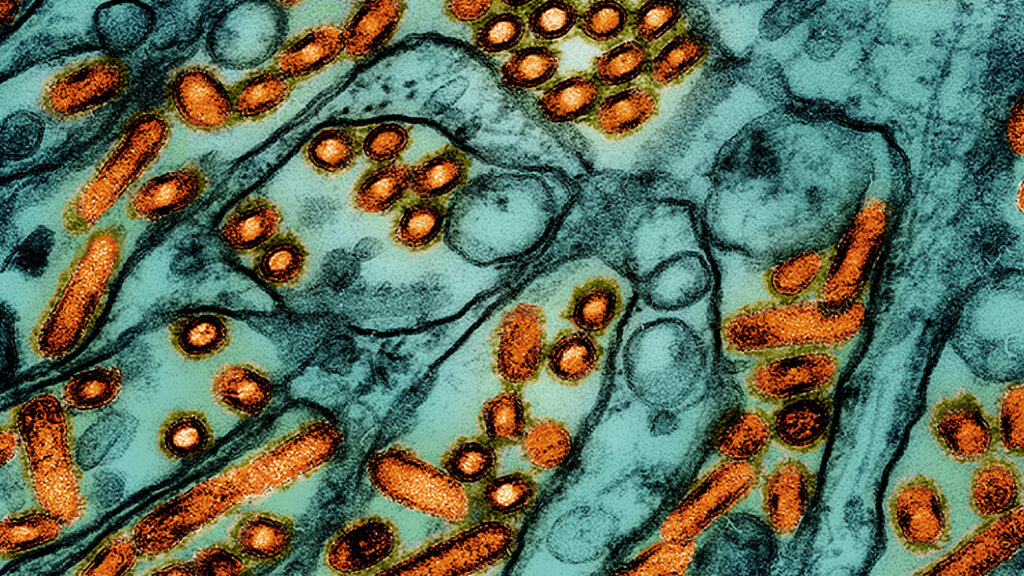

H5N1 bird flu outbreak: Second human case reported, in Michigan

a A second case of bird flu infection linked to the current H5N1 outbreak in dairy cows was discovered Wednesday in a farm worker exposed to infected cows. Michigan state health authorities announced this on Wednesday.

In a statementHealth officials said the individual had mild symptoms and has recovered. Evidence so far suggests this is a sporadic infection, with no signs of ongoing spread, the statement said.

“Farm workers exposed to affected animals have been asked to report even mild symptoms, and testing for the virus has been made available,” Natasha Bagdasarian, the state’s chief medical director, said in the statement.

“The current health risk to the general public remains low,” she added. “This virus is being closely monitored and we have not seen any signs of ongoing human-to-human transmission at this time. This is exactly how public health should work, in early detection and monitoring of new and emerging diseases.”

This is only the third human case of H5N1 ever reported in the United States. A man in Texas who worked on a dairy farm was infected there earlier in this outbreak. The nation’s first case, in spring 2022, occurred in a man in Colorado who was involved in the culling of H5N1-infected birds in a poultry outbreak there.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said a nasal swab from the Michigan farmworker came back negative for influenza. But a swab from the person’s eye was sent to the CDC, where it tested positive for the H5 flu virus, although final confirmation that it is the H5N1 subtype is pending genetic sequencing. This was the only symptom the individual had, the CDC said.

In the Texas case in late March, the only reported symptom was conjunctivitis, also known as pink eye.

“We found this case because we were looking for this case. And we looked for it because we were prepared. And in particular, the state of Michigan was prepared,” CDC’s Deputy Director Nirav Shah said at a news conference hosted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University’s School of Public Health, said she wished other states would search for H5N1 cases as aggressively as Michigan.

“If there is any conclusion to be drawn from this finding, it is that this is probably the tip of the iceberg, as this is the one state that we know of that has done the most in terms of on-farm testing of both cows and also monitoring workers who are on the farm. farms where they found infections in livestock,” she told STAT.

Nuzzo said she took no comfort in the fact that only two human cases have been discovered so far in this outbreak, and worries that people may be reading too much into that low number.

“The failure to find cases is interpreted as reassuring [outbreak] may be something that is waning,” she said. “And I absolutely cannot tell you that this is happening, in part because I think the testing that we do could very well be qualitatively… misleading.”

During the press conference, Dawn O’Connell, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at HHS, revealed that 4.8 million doses of H5N1 vaccine stored in bulk are being put into vials — a process called “fill and finish.” This is just under half of the vaccine believed to be effective against the current H5N1 strain stockpiled in the national pre-pandemic flu vaccine stockpile.

O’Connell said the decision to make the vaccine easier to deploy was made a few weeks ago. “It will take a few months for us to fill and finish the vaccine doses… so I thought it made sense given what we were seeing,” she said.

O’Connell said no decision has been made yet to use the vaccine.

Almost until now 900 people in 24 countries They have been confirmed to be infected with H5N1 since 2003, with most cases linked to exposure to infected poultry. On rare occasions, small clusters of cases have occurred, raising questions about whether there is limited person-to-person spread – something that is difficult to prove when multiple people have the same exposure to infected animals. Continued spread among humans has not been observed, and it is believed that the virus must continue to evolve to spread easily to and among humans.

The outbreak in cattle, known to have occurred for the first time with this virus, was confirmed in late March, although evidence suggests it had been going on for several months before testing identified the cause of a drop in milk production in cows pale.

Since then, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has confirmed outbreaks in 52 herds in nine states, including Michigan. 19 infected herds – more than any other state. (The most recent USDA count does not include the four that Michigan has reported since May 17.)

Post-outbreak experts believe the national number of herds affected significantly underestimates the scale of the problem. Both the USDA and CDC have admitted that farmers have been reluctant to allow testing of their cows or their workers for fear of the stigma attached to the association with the outbreak.

But that has been less the case in Michigan, where state officials have taken a uniquely aggressive stance in their public health response, informed in part by the devastating impact H5N1 has had on the state’s poultry flocks in recent years.

On May 1, Tim Boring, director of the state Department of Agriculture, declared an “extraordinary animal health emergency,” signing an order requiring Michigan farmers to increase biosecurity measures. “Most farms have cooperated well with this,” Boring told STAT in an interview last week.

Farmers were also open to working with local health authorities to fill out questionnaires that could help researchers track how the virus is spreading between dairy herds across the state. “Hundreds and hundreds of farmworkers here in Michigan have been interviewed,” Boring said. “They understand how important it is to understand how this is developing so that we can limit the spread of this.”

Local health authorities have also been monitoring workers at farms with infected herds for symptoms – through regular phone calls to farm supervisors or through automated text messages asking if they have experienced conjunctivitis or flu-like symptoms, even mild ones. Testing is offered to all symptomatic workers who have been exposed to animals on affected farms or who live in a congregate setting with people who have been exposed.

In an interview Wednesday afternoon, Bagdasarian, Michigan’s health official, described the discovery of a human case as a sign that these efforts to find new infections are paying off. “Michigan has really been one of the leading states in testing, so it’s not surprising that we picked up this sporadic case,” she said. At least 35 people have been tested so far, she said. This case is the first to come back positive.

Bagdasarian said officials have seen no evidence of secondary infections. But the state is not yet conducting serological testing — looking for antibodies to H5N1 in the blood of farmworkers and those they have come into contact with — to determine whether there have been unreported cases and possibly even spreading from those individuals to others have spread.

“We have always talked about the need to do additional studies to create more engagement, and to thoroughly investigate serology, especially for people who may have remained asymptomatic the entire time,” Bagdasarian said. “That would be the next step.”

Shah said the CDC would very much like to conduct serological surveys of dairy farm workers, including those, like the Michigan individual, who test positive. “We are not there yet,” he says.

Eric Deeble, the USDA’s acting senior advisor for H5N1, announced at the press conference that additional financial incentives are being planned to try to entice dairy farmers to report infections in their herds and take steps to reduce the risks to cows and farm workers to decrease. Compensation for lost milk – a substantial drop in milk production is the most noticeable sign of infection in a herd – is planned, but will take a few more weeks to complete, he said.

This story has been continuously updated with commentary from the HHS news conference and interviews with Bagdasarian and Nuzzo.