Health

H5N1 testing of some dairy cows ordered to limit the spread of bird flu

Tthe US Department of Agriculture moved to try to limit the spread of the H5N1 bird flu virus among dairy cattle on Wednesday, issuing a federal order that requires an animal to test negative for the virus before it can be moved across state lines. It also requires laboratories and state veterinarians to report to the USDA any animals that have tested positive for H5N1 or another influenza A virus.

In addition, farms that transport livestock across state lines and have animals that test positive for H5N1 or another influenza A virus will be required to open their books to investigators so they can trace movements of livestock from infected herds.

“A negative test is required before they can move. If they test positive, they will have a 30-day waiting period before they can move, and they will need to be retested,” Mike Watson, administrator of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, told a news conference with senior USDA officials. Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The order currently applies to lactating dairy cows, but could be expanded if necessary, Watson said.

FDA representative Don Prater, acting director of the Center of Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, reiterated that although trace amounts of H5N1 RNA have been found in commercially purchased milk products, the agency believes that pasteurization kills the viruses that these findings indicate they were once in the milk. . The FDA announced late Tuesday that it had found evidence of the virus in commercially purchased milk samples.

He sidestepped questions about where the positive milk samples were purchased and what percentage of the samples contained traces of the virus when tested with PCR — polymerase chain reaction tests — by saying the agency has an analysis of its work that “will be made public very soon.” ”

Some support was offered for the oft-repeated claim that pasteurization would kill the virus in milk by Jeanne Marrazzo, the new NIAID director. She said some NIAID-funded researchers had also found PCR-positive milk in samples purchased from stores, but when researchers tried to grow virus from those samples, they were unable to do so.

“The results these researchers got indicated that the PCR-positive material was not alive,” Marrazzo said, although she cautioned that a small number of samples had been worked on and that this will need to be confirmed by the FDA’s larger efforts.

“While this is welcome news, the effort studied a small number of samples that are not necessarily representative of all retail milk,” she said. “So to really understand the scope here, we’ll have to wait for the FDA’s efforts.”

So far, the USDA has reported that 33 herds in eight states have tested positive for H5N1, although a recent analysis of genetic sequences released by the USDA on Sunday suggests the virus is more widespread than previously recognized. Given the size of the U.S. milk supply, the finding of evidence of viruses in dairy products on store shelves also suggests that there have been more infections than have been discovered or at least reported.

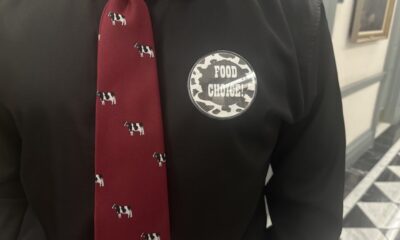

Watson confirmed that USDA has encountered some resistance from farmers they suspected of having infected cows. Farmers have been told to throw away all milk produced by cows infected with the H5N1 virus, although it is not clear if or how that recommendation will be enforced. And evidence that milk containing viruses has entered milk production suggests that some farmers have ignored the advice, or that asymptomatically infected cows may be shedding viruses in their milk.

“There was some reluctance among some producers to let us collect information from their farms. That has been improving here lately,” he said, suggesting the federal decision should also increase USDA access.

“As the federal order goes into effect, this will really help us address any gaps that might exist in terms of … knowing what’s happening to the livestock,” Watson said.

Similarly, Nirav Shah, the CDC’s principal deputy director, acknowledged that there have been some challenges in investigating the health of workers at some farms where H5N1 has been detected.

“We’ve had different levels of involvement with farms,” Shah said. “These situations are challenging. There may be owners who are reluctant to work with public health, not to mention individual employees who may be reluctant to sit down with someone who identifies themselves in some way as a member of the government. ”

He said CDC is working with trusted local sources where outbreaks have been identified, including veterinarians, who have regular access to farms and can serve as “eyes and ears” for public health.

Shah was asked whether wastewater surveillance, which has proven useful in measuring Covid-19 transmission levels in communities, could be useful in detecting H5N1 outbreaks in livestock.

The CDC is looking into the idea, he said, but noted that farms may not be connected to municipal wastewater systems, and that sampling water around farms could lead to false positives if infected wild birds are clustered in an area.