Health

How buildings influence the microbiome and human health

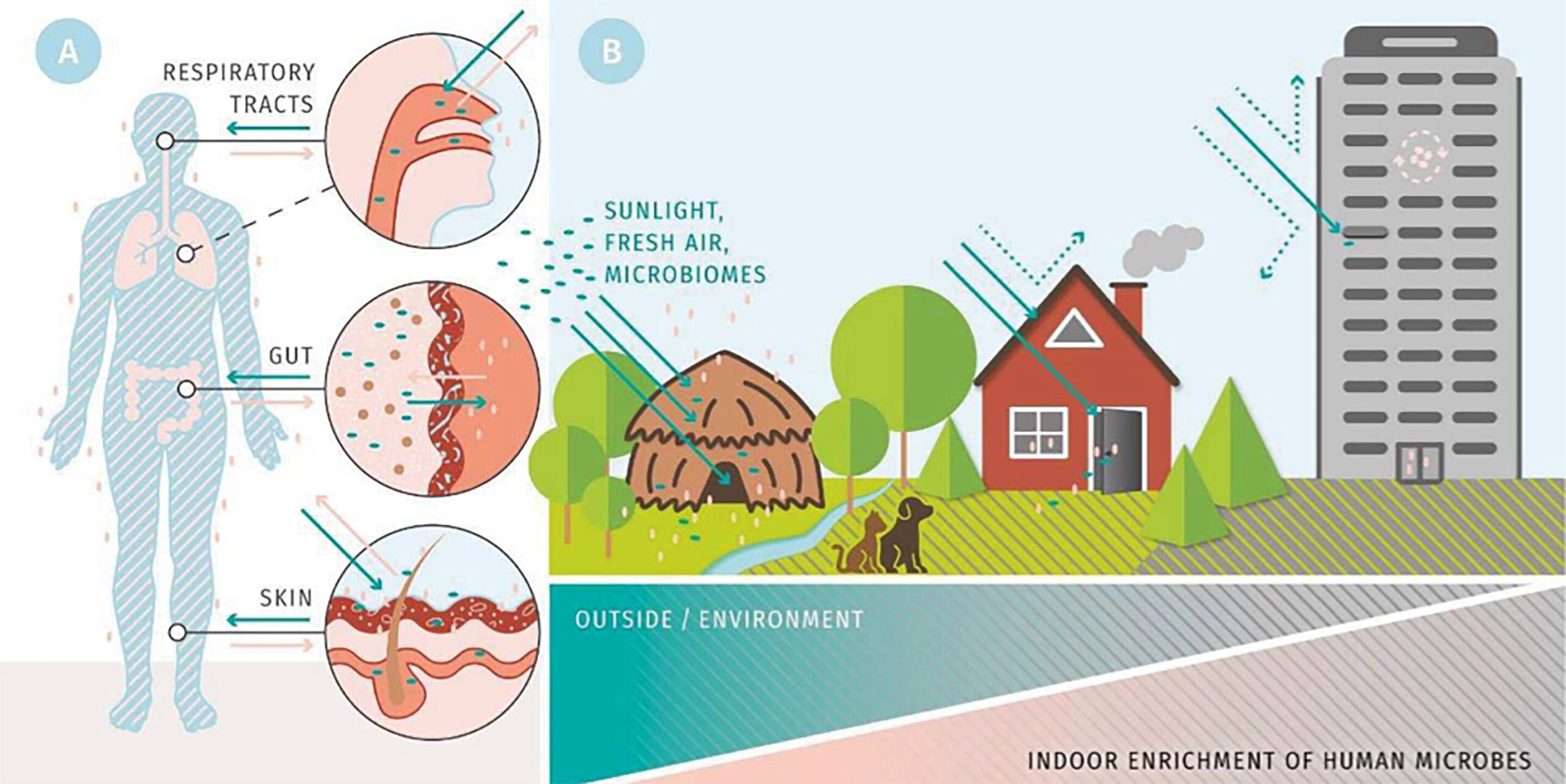

Certain features of modern buildings seem to cause more or less pronounced health disadvantages, as they prevent contact with the multitude of microbes in the natural environment and appear to have overall negative effects on microbial diversity. Credit: Katja Duwe-Schrinner

Over the past twenty years, the life sciences have come to realize that all living things – from the simplest animal and plant organisms to humans – live in close association with a large number of microorganisms. These symbiotic bacteria, viruses and fungi, which colonize on and in their tissues and form the so-called microbiome, together with the multicellular host organism form an especially useful community in the form of a meta-organism.

Many life processes, including the health and disease of the organism as a whole, can only be understood in the context of this functional cooperation between the host organism and microorganisms, for example in nutrient absorption, immune function or neuronal processes.

However, in recent decades, lifestyles in industrialized societies have led to a gradual depletion of the diversity of the human microbiome and this has contributed to the development of so-called environmental diseases, for example inflammatory bowel disease, type 2 diabetes or neurodegenerative disorders.

At the University of Kiel, host-microbe interactions and their effects on health and disease are investigated in detail in the Collaborative Research Center (CRC) 1182 “Origin and Function of Metaorgans.”

A group of scientists involved in the ‘Humans and the Microbiome’ research program at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) in Toronto have published a study perspective paperin Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesproposing a new dimension for the study of the human microbiome and a paradigm shift in urban and building planning.

They discuss the influence of the so-called built environment on the composition and diversity of the microbiome. They put forward the hypothesis that modern buildings have a significant impact on human microbial colonization, depending on their nature and degree of protection from the environment, and that this aspect should be taken into account in future architecture in terms of healthy and microbiome-friendly to build. conditions.

The researchers include Professor Beatriz Colomina of Columbia University, Professor Brendan Bohannan of the University of Oregon, Professor Margaret McFall-Ngai of the California Institute of Technology and board member of CRC 1182 and Kiel Life Science spokesperson Professor Thomas Bosch of the University of Kiel .

Buildings interrupt contact with micro-organisms from the environment

The human search for shelter and protection from the elements is as old as humanity itself; For thousands of years, people around the world have created and developed a wide variety of homes, up to and including the architecture of today; in the near future, more than two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities. Overall, the urban lifestyle, in combination with many other factors, has significantly improved life expectancy and quality of life for the majority of humanity.

“However, buildings as such and the triumph of urban life have also had negative effects by protecting people to a greater or lesser extent from contact with their microbial environment. The extent of these likely adverse consequences for the composition and diversity of the human microbiome can hardly be estimated,” explains CIFAR Fellow Bosch.

The researchers see the main reason for this in the fact that our modern life in the built environment increasingly prevents contact with the multitude of microbes in the natural environment. Furthermore, buildings themselves should be viewed as complex organic systems in the sense of numerous interdependent microbial communities, which also impact the human meta-organism.

Taken together, this has negative consequences, for example by creating new niches for disease hosts and vectors in buildings, concentrating waste and toxic substances or reducing ventilation and sunlight penetration.

All this in turn affects the human microbiome in several ways: for example, the built environment creates new reservoirs of harmful microbes adapted to humans, reduces individuals’ exposure to beneficial microbes, or alters human behavior to prevent natural and beneficial transmission brakes. of microorganisms between people.

“If human health is defined as dependent on a high diversity of the microbiome, then a large proportion of today’s buildings must be considered not conducive to health in terms of construction and design, materials or type of use – because in total their The effects appear to reduce microbial diversity, which could lead to poorer overall health of residents,” Bosch emphasizes.

Future architecture should restore permeability to microorganisms

Since their invention, buildings have often unintentionally caused health problems, even though people have always tried to make them healthier and safer. The research into the links between architecture and health is therefore certainly not new, and a crucial question today is: how can buildings be designed for better health and constructed so that a complex and diverse microbiome can survive?

“By looking at the impact of building features on the human microbiome, we add a completely new and important dimension to this complex. Our urban way of life ignores the fact that the body has adapted to its environment and its microbes over thousands of years. and that it is only fit and healthy in contact with these partner organisms,” says Bosch.

‘Only by accepting this multi-organism complexity will we achieve a deep understanding of health and thus an understanding of common diseases. The completely revolutionary view of living organisms and microbes as a functional unit will also push the boundaries of urban planning in the future. future We offer innovative scientific and applied perspectives for the development of a future, microbiome-friendly architecture that once again enables natural and healthy human contact with microorganisms in the built environment.”

A prerequisite for this is that buildings are developed in the future with the additional aim of dosed and controlled exposure of people, especially to micro-organisms – and no longer see them exclusively as a barrier to ward off environmental influences, as was previously the case.

According to the researchers, one goal could therefore be to plan and construct the built environment in the future in such a way that the focus is not on complete isolation from the natural, microbial environment. On the contrary: buildings can be opened up to nature again and made more nature-friendly.

This can be achieved, for example, by using less toxic building materials and by creating an overall greater structural permeability to external, especially microbial, influences.

“With this perspective, we fundamentally expand our view of the human microbiome and establish a direct link to the built environment through modern urban planning. This results in fascinating new approaches that address microbiome-friendly architecture and construction and may have the potential in the future also reflected in a significantly improved built environment that will be beneficial to human health,” says Bosch.

More information:

Thomas CG Bosch et al., The potential importance of the microbiome of the built environment and its impact on human health, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2313971121

Quote: How Buildings Affect the Microbiome and Human Health (2024, April 26) retrieved April 26, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-microbiome-human-health.html

This document is copyrighted. Except for fair dealing purposes for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.