Technology

How does the visual rabbit illusion fool us so reliably?

In Main tripPopSci explores the relationship between our brains, our senses and the strange things that happen between them.

Imagine this. You’re… somewhere. You have no idea where, because it is pitch black. But then out of nowhere you see three flashes of light in quick succession. They appear to happen along a straight line, each a short distance from the next: the first flash on your left, the second directly in front of you, and the third on your right.

But wait, what did you see? If you suffer from the visual saltation illusion, the second flash actually occurred in the exact same place as the first. There was no flash in the center of your vision; your brain just expected that there should be there a flash so that’s what you saw.

This illusion is also called the visual rabbit illusion, a name it owes to the closely related illusion cutaneous saltation illusion– where participants are quickly tapped on the arm instead of flashes of light. The second tap feels like it happens between the first and third, and in an early article about the illusion – even though it doesn’t. Researchers compared the feeling to a rabbit ‘hopping’ along the arm. (Another version includes a similar auditory effect.)

A recurring theme among illusions is the way many seem to manifest when there is a misalignment between the information the brain expects from the senses and the information it actually receives. For example, the stopped clock illusion is caused by a situation in which the second hand of a clock moves while the eyes are moving, and therefore do not actually see the movement. In that case, the brain intervenes to ‘fill’ the perceptual gap, based on its expectation of when the movement is likely to occur – an expectation that may be incorrect.

[ Related: Why do clock hands seem to slow down? ]

The illusion of a stopped clock involves a clear absence of information: the eyes move when the clock is ticking, thus missing the actual moment when the movement takes place. Does something similar happen with the visual saltation illusion? Yes and no, says Sheryl Anne Manaligod de Jesus, PhD candidate at Kyushu University’s Graduate School of Design and lead author of a new article on the visual saltation illusion published on May 21 in i-Perception.

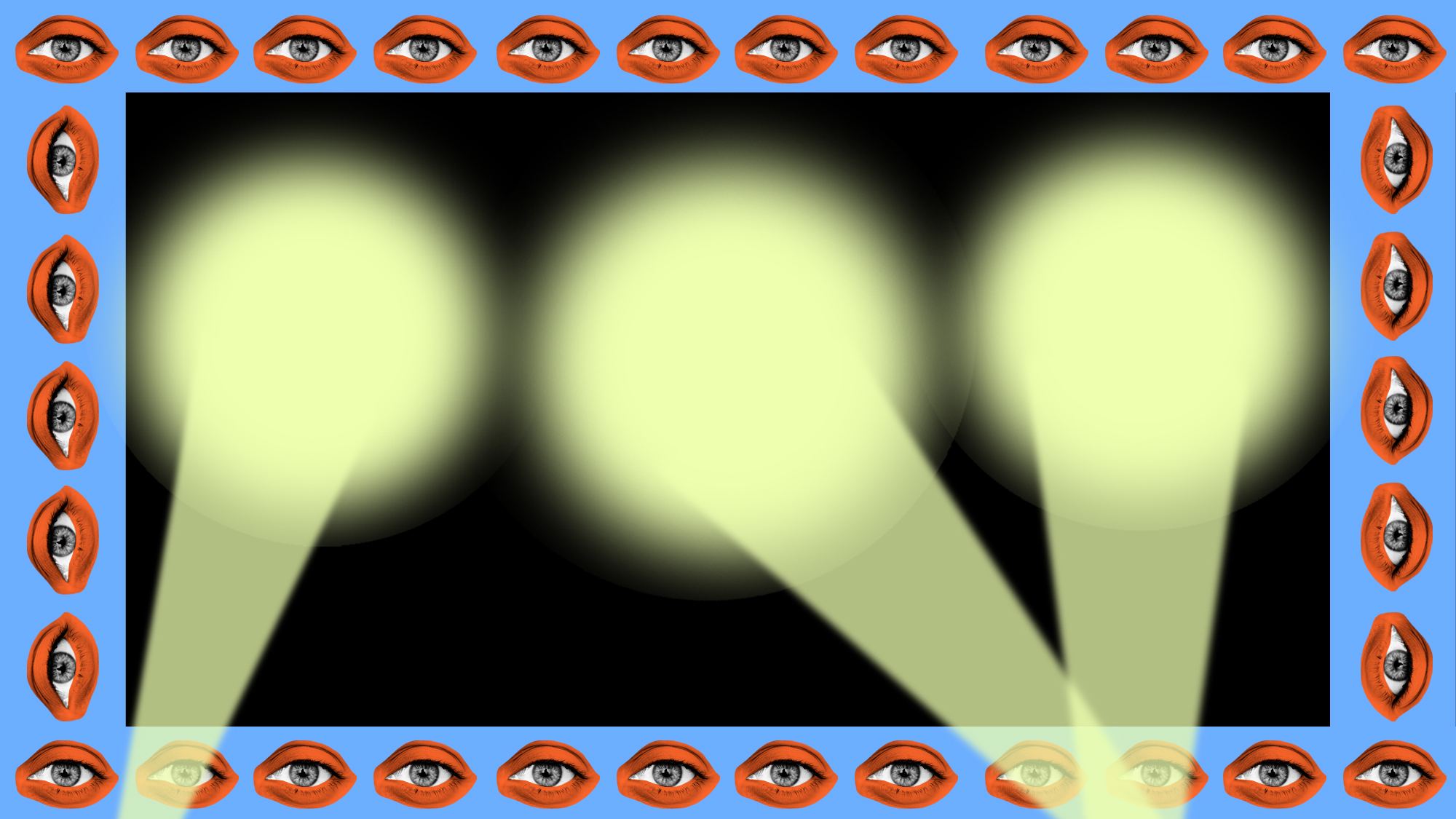

IN THIS IMAGE FROM 2024: Researchers from Kyushu University have further investigated the visual rabbit illusion. The three rabbits represent the actual flashes, while the dots above show where people perceive the points of light. The second dot is usually observed near the center.

“In [this illusion]”, she explains, “The subject ‘sees’ all three flashes, but [they] mislocating the second flash. How does mislocalization happen? De Jesus explains that “the brain misinterprets the information it receives into a pattern that makes the most sense.”

Why however, the brain does this relatively mysteriously. The new research by de Jesus and her colleagues at Kyushu University aimed to further explore the subtleties of the illusion. This was done by making small variations in the design of the experiment, and by examining whether these variations affected the participants’ perception of the illusion. The team’s results suggest that the brain’s desire to place the second flash between the first and third – the location that “makes the most sense” – is remarkably strong.

In the classic experiment, the second flash occurs in the same place as the first. The first change the team made in that experiment was moving the second flash to the same location as the third, an arrangement called the “backward” configuration. The second change increased the number of potential locations for the second flash: in some cases it was placed outside the space between the first and the third. The idea of both these changes, De Jesus explains, was “to test the power of illusion… would ‘going beyond the limits’ still have the same effect?”

In both cases the answer seems to be ‘yes’. Even when the second flash was outside the space bounded by the first and third, participants perceived it in the center of that space. A third change caused the second flash to no longer align linearly with the first and third. Again, participants saw the second flash halfway between the first and third flashes.

There are two main hypotheses to explain this illusion. One is that the brain’s tendency to mislocalize the second flash is based on so-called ‘motion-based position shifts’, while the other is that it is due to ‘perceptual grouping’. As De Jesus explains, the former describes the phenomenon whereby “the position of an object or stimulus… is influenced by movement in the background;” in these cases, participants would “perceive the target object being moved in the direction of motion.”

According to this explanation, the sequential nature of the flashes creates the feeling that the flashes are a single object moving through a participant’s visual field. The new research – and especially the backward configuration – seems to raise questions about this idea: “If [it] If this were true,” De Jesus muses, “the second flash would have been observed to appear after the position of the third flash, and the third flash might also have been perceived incorrectly.”

Perceptual grouping, meanwhile, is a more philosophical explanation: it is based on Gestalt psychology and the idea that “the sum of the parts equals the whole.” This, De Jesus explains, is how we can “see a face in certain works of art, rather than just a bunch of random dots or brushstrokes.” (Another example is Kanisza shapes.)

[ Relate: The mystery of cats and their love of imaginary boxes ]

De Jesus explains that this idea demystifies the visual saltation illusion by suggesting that while the eye sees the three flashes as separate events, the brain interprets that visual information as a description of three parts of a straight line. In other words, as De Jesus puts it, the brain interprets visual data in a way it deems “most appropriate.”

IN THIS 2018 VIDEO: This video, taken from a paper by a team at Caltech, demonstrates a similar phenomenon to the visual saltation effect. In this case, the perception of a second flash between the first and third is triggered by the accompanying beeps, but in both cases the illusion arises from the brain’s expectation of a second flash in a location that ‘makes the most sense’ .‘ to the brain.

In any case, De Jesus warns that the answer to why the brain makes mistakes in this case is not as simple as either/or: “Based on the overall results, we cannot discredit any of them. [theory] or the other.” Instead, she says, more research is needed: “[Using] other devices to measure brain and eye activity would be interesting,” she says, as well as investigating multiple salt illusions simultaneously: “I think it would be interesting to test the same parameters through sound and touch or even a combination of both.”

There are also tantalizing clues for links to other, similar illusions: the Kappa effect, for example, which uses a similar setup to the visual saltation illusion, but moves the flashes in time instead of space. “There is certainly a connection,” De Jesus agrees, “although I cannot say explicitly what [it is]. Both [illusions] are attributed to movement signals and cognitive priors, and perhaps they are linked to the same neural mechanism manifesting in different effects.”