Sports

How the F1 GP’s food surplus in Miami feeds the city and fights climate change

MIAMI GARDENS, Fla. — A Formula 1 Grand Prix weekend is a lot like a Super Bowl event in Miami, especially when it comes to the food.

Extravagant hospitality packages are created, award-winning chefs cater the weekend to bring the taste of South Florida to F1, and VIPs flood the paddock. Over the years, artists such as the Williams sisters, David Beckham, Ed Sheeran, Michael Jordan and Paris Hilton have walked through the Hard Rock Stadium campus. About 242,000 people attended the first Miami Grand Prix, but the restaurant chef teams working on the event weren’t sure what to expect when preparing the meals on campus.

During the three-day weekend, thousands of pounds of food are prepared, ranging from simple ingredients like regular produce to filet mignon. By the end of the 2022 weekend, approximately 90,000 pounds of food remained, amounting to approximately 75,000 meals – a significant amount of food that needed to be rescued.

Food insecurity is increasing in the United States, especially in South Florida. The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion defines the term as ‘an economic and social condition at the household level with limited or insecure access to sufficient food’. In Broward, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach and Monroe counties, nonprofit organization Feeding South Florida found that more than 1.2 million people faced food insecurity on Thanksgiving 2023.

Enter Food Rescue US – the middleman and solution to F1’s food surplus in Miami. The nonprofit has volunteers who pick up viable leftover food (such as food not used for buffets) and deliver the surplus to local agencies, such as homeless shelters and food banks. But if the food wasn’t rescued, it would likely end up in landfills. The South Florida office has worked with Hard Rock Stadium for several years, delivering leftover food from college and professional football games to local organizations.

When F1 came to town, it was only natural that the Food Rescue US – South Florida branch would partner with Hard Rock Stadium again.

“I remember them calling me and saying, ‘So Ellen, we just got F1,’” says Ellen Bowen, site director. “Think of the Super Bowl times three.”

How it works

The food rescue mission won’t begin until after the Grand Prix weekend is over.

During the first year of the race, volunteers spent three days collecting and delivering surplus food, which they defined as food that can be sold or served but doesn’t leave the kitchen. In 2022, this varied from pulled pork to vegetables and pastries. “It was staggering,” Bowen said. “It took us three days to do this, with a total of around 125 volunteers working in four-hour shifts.”

It is impossible to save 100 percent of the extra food; for example, the media catering is in buffet form. But saving 90,000 pounds a year requires significant effort, not only in providing meals but also in keeping food out of the landfill.

“Miami and Broward County are running out of landfills. The incinerators we used burned down last year. So we’re really trying as an organization, and I think as a province, to find a way to reduce the actual waste,” Bowen said. “The organizations that we feed, they’re homeless shelters, they’re community organizations that serve underserved communities. Whether it’s through a church or community center, we put food in community refrigerators. So all the food we rescue goes to people who may have never had a filet mignon, or certainly to people who really need this good, healthy, nutritious food.”

In the second year, fewer volunteers were involved as the existing kitchen staff brought in more employees to help store the food, leaving Food Rescue US – South Florida to coordinate transportation. With one Grand Prix weekend behind them, the kitchen crews knew what to expect, and the food surplus decreased – but it “was quite comparable in quantity to the Super Bowl.”

Bowen estimated that the second year yielded 60,000 pounds of food, which equates to 50,000 meals; in 2024 this number was 65,000 pounds, approximately 55,000 meals. (Tom Garfinkel, managing partner of Miami GP, estimated that the 2024 race brought in 275,000 fans last weekend.) According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a meal weighs about 1.2 pounds, so you divide the weight of the food by 1.2 to estimate the number of meals.

Over the years, the process has remained essentially the same (but this year it was one day shorter): prepared food on the first day, leftover prepared food, salads and produce, as well as unused items such as plates and cups on day two, and herbs and bread on day three. In 2024, the operation took just two days and seven trucks to the six different shelters in Miami-Dade and Broward counties. Bowen said: “If there’s a giant can of tomato sauce that they haven’t used, like large quantities, we’ll take that too, because if you think about it, what happens when the Grand Prix is over, that site gets shut down. , and they don’t want to store things that might be past their expiration date.”

Food Rescue US – South Florida does the same thing during football season, such as when the Dolphins don’t have a home game for two weeks. Bowen said: “It really depends on: can they use it soon? Can they freeze it and then use it? Or is it something they don’t expect to use enough to maintain in the near future?”

The food needs

They also can’t save all the food on campus.

Food Rescue US does not accept hot food, Bowen said. It needs to be cooled and refrigerated so that they only start their F1 activities on the Monday after the race weekend. The food should also be stored in sealed containers and labeled with the food item and the date it was packaged.

However, the organization and chefs also adhere to other guidelines, such as ServSafe (which provides alcohol and food safety training) and the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act. This federal law Bowen essentially ensures that all food donated in good faith is liability free.

When it comes to who will receive the surplus food first, Bowen says she will “try to support the homeless shelters first because they have the capacity to store and freeze bins and bins and bins of food.” She primarily works with four larger shelters, all of which can heat food and handle large quantities of food safely.

The remaining food will be distributed to smaller food banks, which typically do not have full kitchens, like homeless shelters, or the ability to heat the food. They often receive produce and non-perishables because they are “a little more stable and can simply be distributed as groceries.”

A look at the bigger picture

Food insecurity remains a global problem, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. In Florida, affordable housing is limited and gas and grocery prices continue to rise, Bowen said.

“I think people who identify as food insecure now may be people who never identified as food insecure before COVID,” she added. “The statistics are staggering. Forty percent of all food is wasted. Yet I know that in the state of Florida, one in ten people go to bed hungry, and one in five of those are children. So we’re not really doing a good job of feeding our own population, and part of that is feeding them nutritious food as well.”

So Food Rescue US – South Florida focuses on bringing the surplus food to underserved communities, especially food deserts. These areas have no or limited access to healthy and affordable food. Bowen said, “They’re shopping at the local bodega on the corner. They don’t have a Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods in their backyard. They have a cheap supermarket or a bodega where they shop, and many of them who are on welfare have to come up with those dollars.”

Miami neighborhoods categorized as food deserts include Little Haiti, Little Havana, Liberty City, Overtown and Miami Gardens, where Hard Rock Stadium is located and where the Grand Prix is held.

Saving surplus food doesn’t just help feed underserved communities. It also helps reduce the amount of food waste in landfills, ultimately mitigating the long-term effects of climate change.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has found that food waste contributes significantly to climate change. According to a recent report In quantifying methane emissions from U.S. landfills, researchers found that “an estimated 58 percent of fugitive methane emissions (released into the atmosphere) from municipal solid waste landfills come from landfilled food waste.” When organic waste (including food waste) breaks down, it turns into methane, which is created NASA has labeled it “a potent greenhouse gas” that “is the second largest contributor to global warming after carbon dioxide (CO2).” Methane also comes from other sources, such as fossil fuels and agriculture, but diverting food from landfills can help reduce its impact on the climate, the EPA’s study found.

Formula 1 continues to say sustainability is a high priority for the sport and aims to be carbon neutral by 2030. Last month, the company published its Impact Report, reporting that it reduced its carbon footprint by 13 percent between 2018 and 2022. and other charities is a common practice at most F1 circuits, including the Las Vegas Grand Prix, where rescued surplus food is donated to help local communities.

“Anything we can do, and anyone can do,” Bowen said, “will help actually reverse climate change by keeping food out of the landfills.”

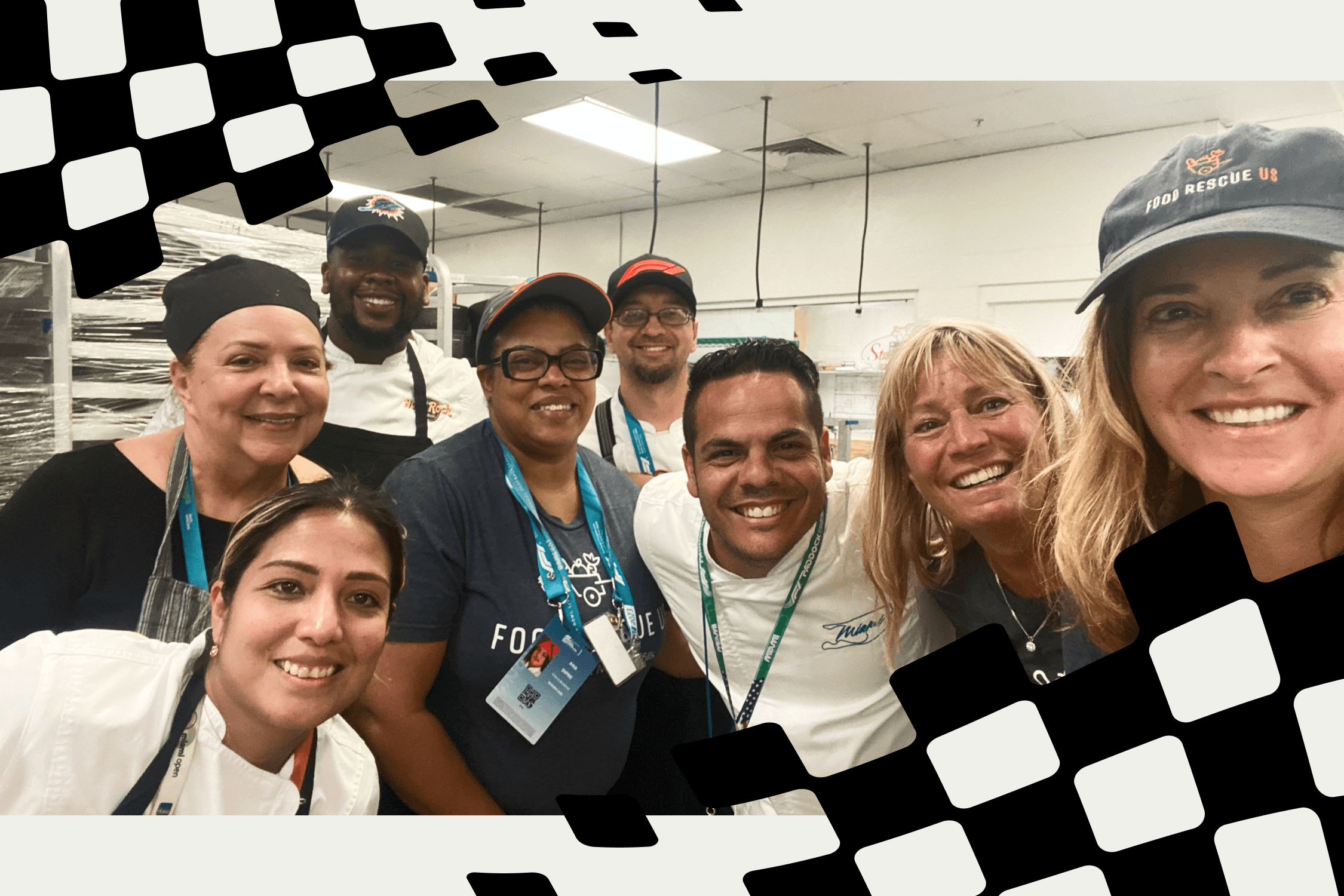

Top photos: Ellen Bowen/Food Rescue USA-South Florida