Finance

Human costs, animal costs and economic costs

People who distinguish between “human costs” and “economic costs” are either making an ideological statement or do not understand what economic theory calls a cost. To give just an example: a Financial times columnist mentioned, as if it were self-evident, the “economic, military and human costs” of further confrontation with Iran’s rulers (“Israel has no good choices regarding Iran”, April 16, 2024).

In economic theory, cost is the sacrifice of something that is scarce (as long as it is one’s time) to pursue a desired outcome or avoid an undesirable outcome. (Note that in both cases the cost is an opportunity cost: avoiding an undesirable outcome implies a more desirable alternative; and what is sacrificed for a desired outcome is scarce because it, or the means to produce it, would be for some other purpose can be used. purpose.) Desired and undesirable outcomes relate only to human individuals and are evaluated in the individual mind. Economic theory is the result of several centuries of scientific effort, by some of humanity’s most brilliant minds, to understand costs, benefits and value in a logically consistent way, and to understand what is going on in society is in hand.

The ideological reason for distinguishing between ‘human costs’ and ‘economic costs’ may be virtue signaling. It amounts to saying, “Look, I’m concerned about the human cost, while my opponents are only concerned about the cost to Sirius, nine light years away from humans”; or “Here is my badge of honor for membership in the bien-pensant society.”

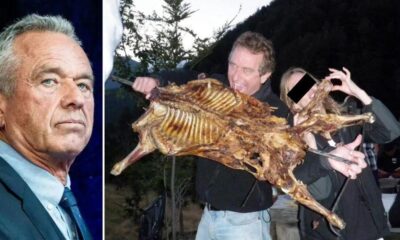

A Mars landing on Earth might think that naming “human costs” (as if there were anything other than human costs) is necessary to distinguish them from animal costs. To lighten the mood, we can think of the costs a bear has to incur for its beer consumption. (See the featured image of this post.)

Back to humans: there is no epistemological objection to labeling a cat as a dog, and a dog as a cat, provided everyone understands which animal is meant. There is no deep epistemological objection to calling “human costs” only those costs that are not borne by shunned or hated individuals – social pariahs, bad capitalists, or individuals whose pension funds are invested in capitalist enterprises. But such a distinction is at best moral, at worst morally arbitrary, and is useless for understanding how society (interindividual relations) works. The distinction between human and economic costs reflects subliminal advertising for highly questionable ideologies.

One objection to my statement is that “economic and human costs” is just a standard language that everyone understands. But my point is precisely that “everyone” wrongly takes it to imply that economic costs are not all human costs. And there are ways in which an economically literate newspaper could adapt the standard expression without losing rhetorical advantage. For example, you could say ‘economic costs, including the costs of life and limb’ or ‘economic costs, including of course all kinds of human costs’. In the Financial times quote at the beginning of this message: the ‘military’ is redundant, except in constructions such as ‘economic costs, including, of course, military costs and the cost of life and limb.’ My fear is that most writers of the Financial timesthink, as in other media, that there are two types of costs: the costs for bad or unpopular people, and the human costs.

******************************

The featured image of this post, a collaboration between your humble blogger and DALL-E, shows a bear paying for his beer, suggesting there are more costs than human costs. That’s news to the checkout girl.