Finance

Injustice and the “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (with Dwayne Betts)

Intro. [Recording date: March 9, 2024.]

Russ Roberts: Today is March 9th, 2024. My guest is poet, lawyer, and author Dwayne Betts. This is Dwayne’s fourth appearance on EconTalk. He was last here in January of 2023 talking about beauty, prison, and redaction. He was a MacArthur Fellow in 2021. He is the founder of the Freedom Reads project, which puts Great Books in prison. We’ll talk about that later or maybe earlier. Dwayne, welcome back to EconTalk.

Dwayne Betts: It’s my absolute, absolute pleasure.

Russ Roberts: Our topic for today is Martin Luther King Jr.’s [MLK’s] “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” and your introduction to a new volume of King’s work. How did this come about?

Dwayne Betts: It’s actually remarkable because in my life, all good things that I’ve gotten–and I swear this is true–have come when I tried to do something for others. And so, for the first time, the King family had okayed a collection of books, individual books to come out that were based on the speeches. And, the first book was I Have a Dream, and the introduction was written by King’s children. And, it’s cool. The book is actually paginated and laid out as King spoke, so you could actually read it and kind of embody his voice, almost like a poem, almost like really living in the words. They wanted to get the books into prison.

And my friend, Brother Yao, Hoke S. Glover, who I met when I came home from prison, less than a month out of prison, I had read all of the books on this. He was selling books on a cart and I had read, like, all of them. He said, ‘What college do you go to?’ I hadn’t finished college. He said, ‘What school you go to?’ I looked. I was like, ‘Look, man, I just got out of prison.’ And then, he asked me, ‘So, you’re a poet?’ Who asked that question after hearing the word ‘prison’?

I told him yes, and we developed a friendship; and I ended up working at this black-owned bookstore called Karibu Books. So, much of my life came from that. But, he knew the people at Harper Collins and they wanted to get the book into prisons. And, so, he introduced me to the folks and we were having a conversation. They told me about the project and I said, ‘Wait a minute. Did Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ever write anything about prison?’

And, mind you, I know he did, but I must’ve just been so overwhelmed with the moment thinking that–because I could say we are going to put 1500 copies of this book in the prisons across this country. And, it felt meaningful. Because that meant that I did it with debt[?], I did it with Primo Levi. It meant that I was doing this thing that mattered and I was doing it for the kaleidoscope of the world that I cared about. They said, ‘Yeah, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”‘ And, I said, ‘What kind of fool am I?’

And I said, ‘Wait a minute. Let me ask you something.’ Because they had people writing the introductions. I said, ‘Does anybody write the introduction for that one? Because I should write that one. I’m going to tell you why.’ But, they said, ‘Well, hold on, let us just check real quick.’ And, they was, like, ‘Strangely, we have people for all of them except that one.’

I was, like, ‘Look, let me tell you a story. Now I get locked up on December 8th, and December 9th, I go to court and I find out that I’m going to miss Christmas.’

And, I start crying uncontrollably, man, because the new PlayStation was coming out, and I just knew I was going to get one. But, also, man, I was not going to see my mom until the New Year. That’s what they told me. That lets you know that I had no understanding that I wouldn’t see my mom for a lot of New Years. But I told him, I explained that I only cried twice in prison, and it was that day; and then it was the next year, I was on the top bunk. And, it was one of these MLK days and I had heard this story time and time again, but, man, that day I heard it–Bus Boycott, Edmund Pettus Bridge, civil rights movement. And, I couldn’t stop crying.

I mean, I knew I had just wasted my life, man, for a pistol and $10. And, I tell them this story: I said, ‘Man, I got to write this introduction.’ And they, like, ‘Cool story, but family, permissions, I don’t know if this is going to happen, bro. But, I like you. We like you. We like Freedom Reads. Let us check it out. Let us see if the family will approve this.’ And, I thought to myself, ‘Why–why would they approve me?’ So, I let it go. And three, four days later, they hit me up and they said, ‘Dwayne, you wouldn’t believe this. You were on a short list of people already approved by the family to write any of these introductions.’

I have a hard time believing that. In prison, you got to have faith especially when you’re the most vulnerable person in prison. And, that’s where I was at least amongst the top 2% of most vulnerable people in the penitentiary–120 pounds, 16 years old in a state that I wasn’t from. No friends, no cousins, no family. You got to have faith, you know. But, you come home and you think everything you do on the outside is governed by your own hands.

And every once in a while, it’s just remarkable the way I get reminded that, man, who would have thought this would have happened? And that’s the story.

Russ Roberts: Amazing. We’ve talked about this in previous episodes, but you were in prison–you said for a pistol and $10. You had carjacked someone. You were 16, I think. And, how long did you spend in prison?

Dwayne Betts: Yeah, I was 16. Carjacked this guy. And, I carjacked two women. I hate saying that because it’s like doubling down on ignorance. But, I was sentenced–I pled guilty and I didn’t know how much time I would be sentenced to. And, I stood in front of the judge facing life and he sentenced me to nine years in prison. He told me, ‘I’m under no illusion that sending you to prison will help, but you could get something out of it if you want.’ I never forgot that and I hope I got something out of it. But I spent about eight years and three months inside.

And, I came home on the most poetic day on the calendar. I came home on March 4th, which is the only date that is both a date and a command. I swear, man: I’m telling you, God has a sense of humor. Yeah.

Russ Roberts: Let’s talk about King’s letter. I have to say, reading it in 2024 feels like time travel. It was written, I think, in 1963, which is not so long ago. I was nine years old. I remember Martin Luther King Jr. as a figure, as a person in the news. But that letter reads from such a different time. He’s fighting segregation in Alabama, and elsewhere, of course. He’s fighting the mistreatment of blacks and the humiliation of blacks in segregated water fountains, segregated restaurants, segregated hotels–you name it.

That’s the first part that’s time travel. Again, I’m old enough to remember. I had been in the South as a boy and I remember water fountains that were for whites only.

But, the other part that’s time-travel-y for me in that essay, his letter, is he writes a lot about the Church and religion as a vibrant part of American life. And, it is much less so, both the Church and religion.

But, let’s begin with a little bit of history. King is in jail. Why is he in jail and why is he writing this letter?

Dwayne Betts: He’s in jail for being a part of a nonviolent demonstration against segregation. And what’s interesting, though, is that, for me, the reminder is that the most acceptable way to really torture somebody and make them suffer has always been incarceration. But, what’s telling in this case is that the imprisonment was really also meant to shame. And, I think that everybody who was a civil right protester at that time had to accept the idea that they would face an experience that they had lived their whole life finding abhorrent. And, it’s kind of interesting in that way.

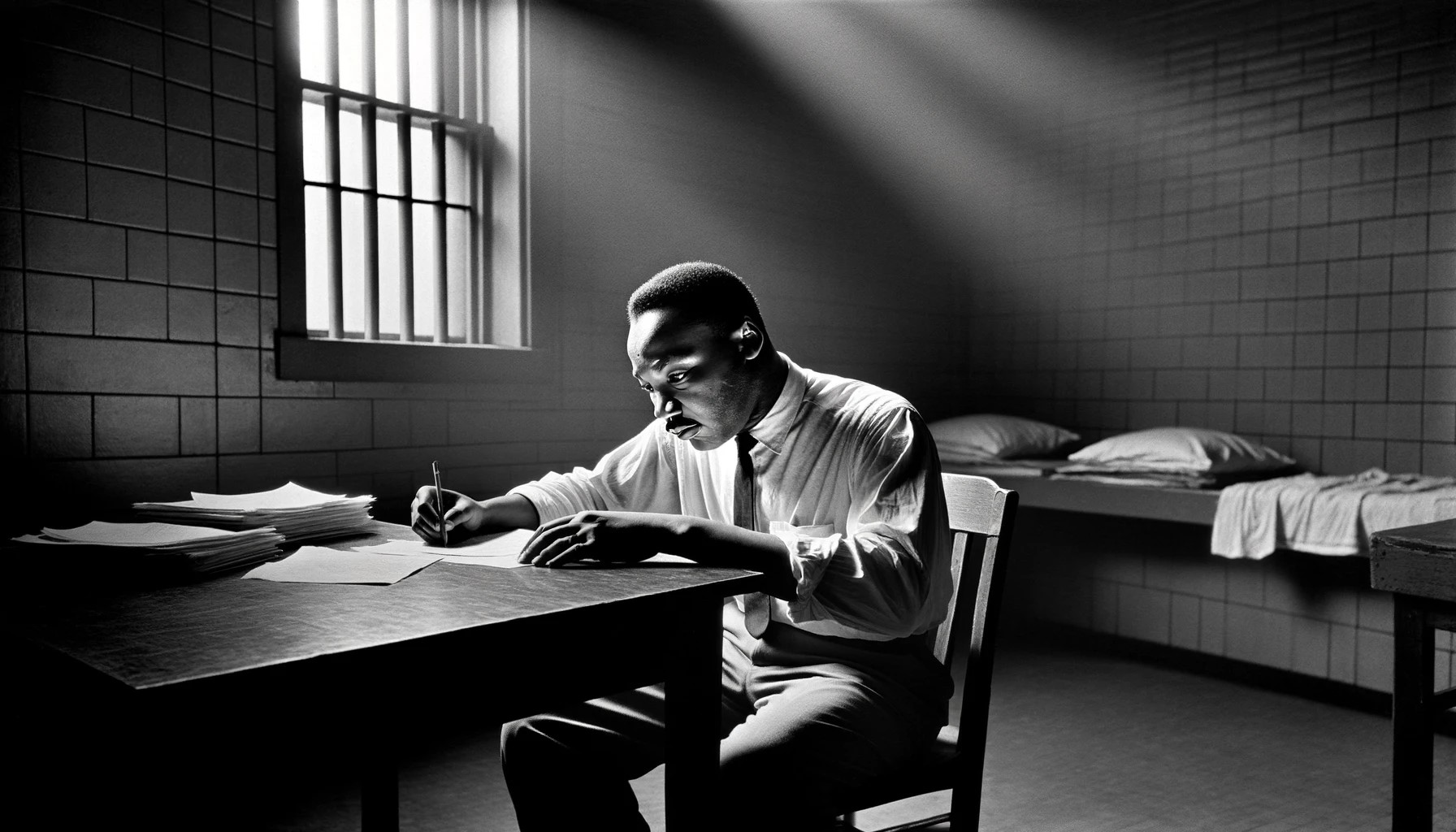

But, he’s in a Birmingham jail; and he’s being criticized. They wrote an op-ed. It was eight clergyman, and it was moderate clergy. They were white religious leaders of the South who made a public statement of concern and caution; and was telling about King’s responses that–it’s time travel but it’s not. Because, once you understand how it was written, you realize that this is in some ways Navalny. This is in some ways some kid in solitary confinement. This is in some ways Guantanamo Bay. Which is to say that he is writing it on scraps of paper and anything he can find; and the urgency in it is the same urgency that we have whenever we want to communicate.

And actually, I find that he honored those eight men in writing a letter. He says: ‘If I were to pause and answer every criticism’–that’s so tongue-in-cheek. It’s so beautifully rhetorical, right? He says, like, ‘I don’t have enough time to talk to people about this work. But, if I talk to you, then I know I’m not just talking to you. I am talking to history. I am talking to the world.’ He said, ‘I take you serious enough to respond.’

And, I do think the greatest care we can pay is attention. And to pay that kind of attention in a longhand letter written without the aid of books, without the aid of his secretaries, without the aid of dictation, I find completely remarkable.

But even more than that, I find it remarkable that–now, we live in a world that is so angry, right? And he was able to write this letter with, I think, deep compassion; and not just deep compassion for the black folks in the South, but I think deep compassion for this country. Which, you say that religion has kind of–it’s not as vibrant today as before. It’s true.

I also think probably when our struggles were so obvious that it was just much easier to pick winners and losers. And, nowadays, I feel like it’s much more challenging to name what the side of justice looks like.

Sometimes we just perform our opinions as if they come from–I do it, too, though; so I won’t begrudge anybody else. But, it doesn’t feel like it when I read this letter. When I had to go back and read it again, it felt like somebody writing from a deep, deep sense of conviction. And, somebody who spent so many words–he’s, like, ‘I don’t have enough time.’ And, this is, like, the most thorough letter that one could imagine. It’s actually like a tutorial about what it means to engage in nonviolent protest. It’s a beautiful thing because it seems like he says: ‘I don’t think you know what we’re doing or why. And, so, let me tell you both.’

And, I guess it becomes a challenge. I wonder what the eight men–those religious leaders who he wrote to–did in the face of such clear and unrelenting both argument, but also just that gut-wrenching ‘let me tell you why I’m here.’

Russ Roberts: The eloquence is astounding, and as you point out, he’s entitled to a rant. But it’s not a rant. It’s a–it’s really a love letter to–not a love letter to the clergy, but it is a love letter to justice in his country. And, it is filled with compassion for those two things, and it’s quite beautiful. Of course, we’ll link to it. You can read it–it’s spectacular–if you’ve not read it before.

It’s not long but it’s not short, right? As you say, the thoroughness is astounding in terms of rhetoric and themes to explain and justify why he has done what he has done and why he will continue to do what he will do.

But, what are some of the themes of his argument, his defense of what he’s been doing?

Dwayne Betts: I think the biggest theme is time. You know: When is it time to protest?

And, it’s interesting because, like, see, the beauty of it is when you say, when he says a line that says something like we know through–I’ll read it directly.

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.

And, what’s really interesting here is that it was easy to name the oppressed and the oppressor. My mom was three years old in 1963, and I was born in 1980, which means from 1963 to 1980, this world, this country changed radically. It changed so much so that you can’t even use those words in the same way anymore. You can’t say in the same way–you cannot say that black Americans are the oppressed. You cannot say that white Americans are the oppressor.

So, for me, it’s just humbling to say that we changed the world. We changed this country.

And, what he says, though, is that I have never been a part of a movement to change the world that happened on a timeline that the oppressor set.

And, I think that is the first point, because I do think that we are thinking about dignity and we are thinking about what people have the right to do.

And, those eight clergy was saying: ‘Well, you have the right to freedom. You have the right to justice. But, you don’t have the right to disruption.’

And I think that he just found that insulting. Because, to tell somebody who is not oppressed, who is clearly–and is also not the oppressor, but they standing around watching. And, I think he’s, like, ‘Wait a minute, you don’t get to say it.’ And to me, that theme there is the one that gets you that notion: Justice too long-delayed is justice denied.

And, so, for me, that is one of the dominant themes.

I think the other theme, though, that I go back to, really, is I ask myself what am I doing in the world? It is when he says, ‘Well, you want to know why we do this?’ Now, I came out of prison and I remember going to church one day. Right? And, it was on an MLK day. I was 27 years old. And he said, ‘Stand up if you’re over 26.’ And, you know, it’s the first time that I felt like a man amongst men. And I was proud. I stand up with everybody else.

And, he said, ‘By the time Dr. Martin Luther King was 27 years old, he had already led the Bus Boycotts. He had already faced death.’ And, I thought to myself, ‘Wow. What have I done with my life, again?’ And so, when he says, ‘Why sit-insurance? Why marches? Why all of these things? Why not just negotiate?’ And then, he frames out what it means to take direct action, what it means to take those steps–from study, from purification, from being prepared to understand why you are going to break a law and knowing you are going to break a law–I feel like that’s one of the major themes, too. Because, if you weren’t there, it’s hard to even understand. I think for me, it was hard to understand the work that went into this. It was hard to know that this was a thing that wasn’t just developed overnight.

And so, I think one of the other themes is that: and this is work, and you should respect my work.

I do think that he was saying to these clergy, ‘You don’t know my work. And, the fact that you don’t know it and would criticize it and not respect it, that’s actually worse than standing on the sideline.’ That’s like standing on the sideline and then pulling out your trumpet as if you were invited to get on the stage with Miles Davis. It’s like, you weren’t invited to this party. Right?

And, I think that–that’s that other theme in there.

And then, finally, for me, I should just say you’re talking about six pages, single spaced, written from a prison. One could argue that every single paragraph has 50 themes that we could spend the entire day discussing. But it’s this thing that I come back to: when he’s, like, ‘But, let me also tell you the obligation and duty of the contemporary church to act. Let me say that there was a time when the church was powerful, and the church was powerful because the church was a mover in the lives of people.’

And, you could substitute church for government. You could substitute church for family. You could substitute church for your mother, your father. But, I think the point is that he was calling all of us to account for the ways in which we had allowed ourselves to not be accountable for what happens tomorrow, and all of the excuses we had for not being accountable.

Russ Roberts: I want to talk about a couple of those themes. The first, the theme of time, which is basically that–the white clergymen, in their piece, it essentially said, ‘Just wait. Just wait.’ And, King’s answer is: Waiting often means never.

And, I think about the Civil War–500,000, 600,000 people dead. And people have said–and I think they’ve said it on this program over the 18 years; and, I know people have said it elsewhere–that slavery’s end was inevitable. And, rather than the North forcing the Union and ending slavery, they could have just waited and it would have died a natural death.

Well, it’s easy to say.

And, of course, there are untold suffering and death in the meanwhile. I’m not suggesting there’s a calculus that would help us assess the deaths of 600,000 people on the other side of that.

But certainly it’s easy to say, after the fact: ‘Well, it would have ended anyway.’

But, we don’t know that in any real sense. And, King says in the following way, he says, quote–and this, by the way is you could call it social science, applied history, whatever you want to call it; it’s really beautiful. He says:

Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be coworkers with God. And, without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right. Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy and transform our pending national elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood. Now is the time to lift our national policy from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of human dignity.

Dwayne Betts: He can write.

Russ Roberts: Yeah. The rhythm–and, like you say, it’s a poem. It’s got a cadence, a beautiful cadence to it.

I want to read another excerpt about the church, but do you want to react to that at all? Besides he can write? Yes, he can.

Dwayne Betts: Yeah. But, also, I think that you hear it, man, and it takes you to a destination.

And, he was sayin’, ‘You know, he could name this thing, even if other folks don’t expect us to name it.’

And, I should just say, also, in that naming, right? He also doesn’t–it’s not just, it’s not an indictment of white people. He names the names of people who were on that journey with him. He names the names of the white clergy who were marching with them, who were tossed in the roach-infested cells with them in [?].

And so, the beautiful thing about that is when you take it out of context, you might imagine that we were talking about something that didn’t look like what he wanted America to look like. But in fact, it was.

And, it is beautiful because he says, ‘Let me give you this beautiful image.’ And, then, he’ll come back and give you the names. He’d be like, ‘Ralph McGill, Lillian Smith, Harry Golden, James Dobbs, these people who I’ve never heard of, who I don’t know exist. But, when you read it again and again, you realize, ‘Oh, nah. He’s making a point. I am disappointed in you, eight. I am not disappointed in everybody.

Russ Roberts: And, he does not name them.

Dwayne Betts: Nope. Which is so–that is, like, the mark of humility. But also it is the mark of: ‘I will not turn this into something that is actually about you. Thank you for being in my vehicle, my vessel, the catalyst’–I was about to say the Cadillac, ‘that’s driving me to the urgency of this message; but thank you for being the catalyst.’

That’s actually really beautiful. Because most of us–I know I would–I’d be naming the names of everybody that’s offended me. Especially these days. [More to come, 24:43]