Health

Is a long life without disease possible? A rare genetic syndrome may lead the way

Ecuadorian doctor Jaime Guevara Aguirre examines patients Maritza Valarezo (L) and her sister … [+]

We hear the words “genetic mutation” and tense: if it’s a mutation, it must be a bad thing, right? Not always. In some cases, a mutation can have protective or beneficial effects. These types of gene variants are a research hotspot because they hold the promise of new treatments. If we understand how the mutation works, we may be able to artificially mimic its protective effects.

Laron syndrome, technically known as growth hormone receptor deficiency (GHRD), falls into this category. Individuals with the syndrome are much less likely to suffer from age-related diseases such as cancer and diabetes. a new study suggests they may also be more resilient to heart attacks and other cardiovascular problems.

What is Laron Syndrome?

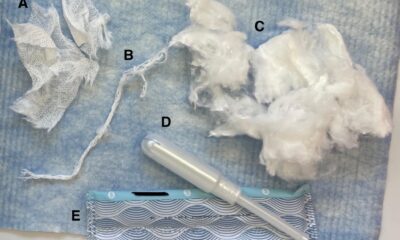

Laron syndrome is an extremely rare condition – there are fewer than 500 confirmed cases in the world – caused by mutations in the growth hormone receptor gene (GHR). As with any gene, the DNA strand that encompasses the growth hormone receptor is made up of thousands of ‘base pairs’ – the chemicals that form the basis of DNA. Just a single change in one of these base pairs can be enough to cause a difference in the function of the protein the gene encodes.

These changes in the growth hormone receptor gene interfere with the production of important proteins involved in children’s growth. As a result, people with the syndrome are almost never taller than 1.5 meters. They are also prone to developing obesity and tend to have higher levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), or “bad cholesterol.”

Despite this, people with Laron syndrome live long compared to unaffected relatives. Back in 2011a group of researchers suggested that this could be due to virtually non-existent levels of cancer and type 2 diabetes, fortunate protective byproducts of the genetic mutation that causes the syndrome. Individuals with Laron syndrome tend to produce less growth hormone called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which, while crucial for growth during childhood, has also been linked to the type of disrupted cellular proliferation that occurs leads to cancerous tumors.

The same lifespan extension has been observed in mice with Laron syndrome, which, compared to their peers, tend to live 40% longer. They also develop fewer tumors and exhibit the same smaller stature.

Another possible explanation for the longer lifespans of people with Laron syndrome is the fact that their cells are significantly more likely to self-destruct after sustaining damage than those of unaffected individuals. This prevents the cells from sustaining mutations or DNA damage over repeated generations, which is considered one of the hallmarks (and possible causes) of aging.

The same group of researchers, led by Dr. Jaime Guevara-Aguirre of San Francisco de Quito University and Dr. Valter D. Longo of the University of Southern California, followed up these initial findings with a second study from 2017. This time, their research showed that the protective effects of the syndrome were not limited to the body alone: cognitive performance also remained high with age, and there were hardly any cases of dementia. Overall, the brain function of older adults with Laron syndrome was closer to that of younger adults in the general population.

What about heart health?

But one big question mark remained. Many researchers speculated that since people with the syndrome were more likely to develop obesity, they would also be more likely to develop heart problems. These problems may outweigh the protective factors. To answer this question, Dr. Guevara-Aguirre and colleagues returned to the Ecuadorian families they had worked with in the past. They recruited 24 individuals with the syndrome and compared them with their unaffected relatives.

The results suggest that people with growth factor deficiency are no more likely to have heart problems than their unaffected counterparts. The syndrome appears to be at least somewhat protective against cardiovascular disease. Affected individuals had lower blood pressure and glucose levels. They also had fewer problems with atherosclerosis, in which plaque builds up in the arteries and begins to restrict blood flow. If left untreated, which is not uncommon because it is difficult to notice, plaque buildup can lead to heart attacks and strokes.

Same but different: Not all individuals with Laron syndrome share protective benefits

Something worth mentioning is that not all individuals with Laron syndrome experience the same protective effects. Zvi Laron, professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, was the first to recognize and define the syndrome in 1966 – which is why it bears his last name. But among the population it does he studiedconsisting of blood-related Jewish families from Yemen, was part of the patients did develop insulin intolerance and diabetes. Furthermore, only a handful of individuals showed the usual resilience to cancer seen in Ecuadorian families with Laron syndrome.

How should we understand these discrepancies? Laron syndrome is caused by mutations in the growth hormone receptor gene, but these mutations can take many different forms. More or less of the gene can be affected, in different areas. So even though all individuals in question suffer from the same syndrome, it can be caused by subtly different mutations. To date, we know of 17 different genetic mutations that cause the disease. Based on Zvi Laron’s research, it appears that the protective benefits against cancer are only present if both parents share the same mutation in the same place and pass it on to their child, known as homozygosity.

The Ecuadorian community, whose roots can be traced back to the Sephardic Jews who fled Spain during the Inquisition, all share the same mutation. It could just be that this particular mutation is the one that happens to confer longevity benefits. In that case, focusing on this community may be beneficial when it comes to developing treatments that mimic the life-extending and disease-fighting properties of the syndrome.

Implications

Although Laron syndrome presents obvious challenges, it also appears to offer certain benefits. Those with the condition, at least the Ecuadorian contingent, live longer and suffer fewer age-related diseases than their unaffected counterparts. Most of these benefits can be traced back to reduced levels of insulin-like growth factor 1.

By studying the syndrome and learning more about its effects at the molecular level, we may discover ways to transfer its protective effects to the general population. The point here is not necessarily to ensure longevity, but to increase “health span,” the number of years of your life you spend in good health. Dr. Valter D. Longo – the lead author of the study – did indeed experiment with it fasting-like diets which can reduce the levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 circulating in the body, and thus several risk factors for disease. There are also molecules that block the protein, slowing the growth of cancer. By refining these approaches, the syndrome’s protective effects could soon be available to everyone.