Health

Living at higher altitudes in India is associated with an increased risk of stunting in children

Credit: Pixabay/CC0 public domain

Living at higher altitudes in India is linked to an increased risk of stunting, with children living in homes 2,000 meters or more above sea level at 40% higher risk than children living 1,000 meters lower, according to research published in BMJ Nutrition prevention and health.

Children living in rural areas appear to be the most vulnerable, prompting researchers to call for prioritizing nutrition programs in hilly and mountainous regions of the country.

Despite several initiatives, stunted growth in children caused by chronic malnutrition remains a major public health problem in India, affecting more than a third of five-year-olds, the researchers noted.

Although research from other countries shows a link between residential height and stunted growth, it is not clear whether this could also apply in India, where a substantial number of people live more than 2,500 meters above sea level.

To investigate this further, the researchers used data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015-2016, a nationally representative household survey in India. About 167,555 children under the age of 5 from across the country were included in the analysis. GPS data was used to categorize height level, while the World Health Organization (WHO) standard was used to define stunting.

Most (98%; 164,874) children lived less than 1,000 m above sea level; 1.4% (2,346) lived between 1,000 and 1,999 meters above sea level; and 0.2% (335) lived at or above 2,000 meters altitude. Seven in ten lived in the countryside.

The overall prevalence of stunting among these children was 36%, with a higher prevalence among children aged 18-59 months (41%) than among children younger than 18 months (27%).

Stunting was more common among children of the third or higher birth class (44%) than among first-borns (30%). The rate of stunting was even higher among children who were small or very small at birth (45%).

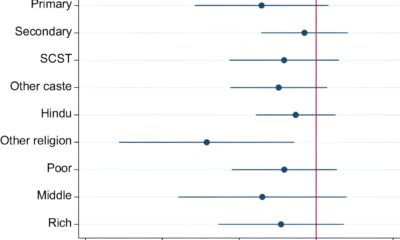

Mothers’ education emerged as an influential factor: the prevalence of stunting decreased as maternal education level increased. The proportion of children whose mothers had no education was more than double that of children whose mothers had higher education: 48% vs. 21%.

Other protective factors included elements of prenatal care such as clinic visits, tetanus vaccination, and iron and folic acid supplements; proximity to health facilities; and not belonging to any particular caste or tribe.

This is an observational study that captured a snapshot of the population at a specific point in time, making it difficult to confirm that height is a cause of stunting, the researchers acknowledge. But there are plausible explanations for their findings, they suggest. For example, chronic exposure to high altitude can reduce appetite, limit oxygen supply to tissues, and limit nutrient absorption.

Food insecurity also tends to be greater at higher elevations, where crop yields are lower and the climate is harsher. Similarly, health care facilities, including implementing nutrition programs, and access to health care are also more challenging, they suggest.

“In summary, concerted efforts are needed across the health and nutrition sectors to address stunting, focusing on children at higher risk in vulnerable areas,” they conclude.

“A multifaceted approach should combine reproductive health initiatives, women’s nutrition programs, infant and young child feeding interventions, and food safety measures. Continued research, monitoring and evaluation will be critical to drive evidence-based policy and targeted action to ensure that every Indian child has the opportunity for healthy growth and development.”

Professor Sumantra Ray, Executive Director of the NNEdPro Global Institute for Food, Nutrition and Health, which co-owns BMJ Nutrition prevention and health of BMJ, adds, “Over the past decades, public health interventions in India have effectively addressed previously prevalent nutritional problems, such as iodine deficiency, associated with living at higher altitudes.

“But this study highlights the complexity of malnutrition in hilly regions where broader determinants of malnutrition among children under 5 years require further research to elucidate the relative contributions of heredity, environment, lifestyle and socio-economic factors.”

More information:

Geographical height and stunting among children under 5 years in India, BMJ Nutrition prevention and health (2024). DOI: 10.1136/bmjnph-2024-000895

Quote: Living at higher altitudes in India linked to increased risk of stunting in children (2024, April 25) retrieved on April 25, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-higher-altitudes-india-linked-childhood .html

This document is copyrighted. Except for fair dealing purposes for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.