World News

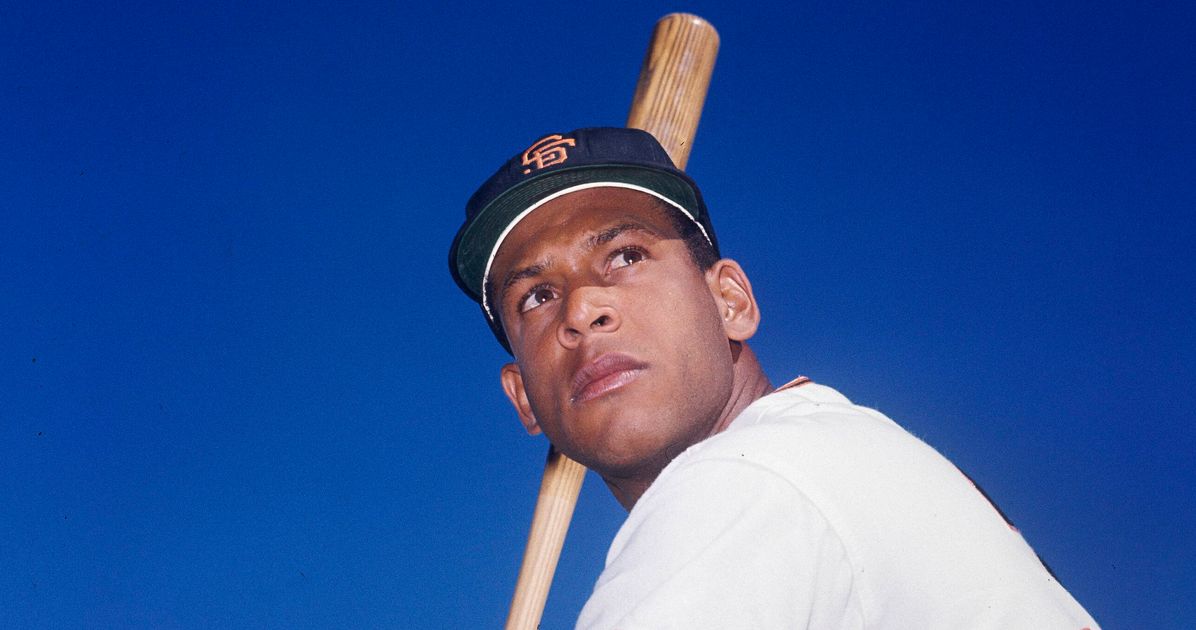

Orlando Cepeda, Hall Of Fame Slugger Nicknamed ‘Baby Bull’, Dies At 86

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — Orlando Cepeda, the lanky first baseman nicknamed “Baby Bull” who became a Hall of Famer among the early Puerto Ricans who starred in the major leagues, has died. He was 86.

The San Francisco Giants and his family announced the death Friday evening, and a moment of silence was held as his photo was displayed on the scoreboard at Oracle Park midway through a game against the Los Angeles Dodgers.

“Our beloved Orlando passed away peacefully at home tonight, listening to his favorite music and surrounded by his loved ones,” his wife Nydia said in a statement released through the team. “We take comfort in the fact that he is at peace.”

Cepeda was a regular at Giants home games throughout the 2017 season until he faced some health issues. He was hospitalized in the Bay Area in February 2018 after a cardiac event.

One of the first Puerto Rican stars in the majors but limited by knee problems, he became Boston’s first designated hitter and credits his time as a DH for inducting him into the Hall of Fame in 1999, as selected by the Veterans Committee.

“Orlando Cepeda’s unabashed love for the game of baseball shone through his extraordinary playing career, and later as one of the game’s enduring ambassadors,” said Hall of Fame Chairman Jane Forbes Clark. “We will miss his beautiful smile during Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, where his spirit will forever shine, and we extend our deepest condolences to the Cepeda family.”

When the Red Sox called Cepeda in December 1972 to inquire about becoming their first designated hitter, the unemployed player accepted on the spot.

“Boston called and asked me if I was interested in being a DH, and I said yes,” Cepeda recalled in a 2013 interview with The Associated Press in the DH’s 40th year. “The DH got me into the Hall of Fame. The line got me into the Hall of Fame.

He didn’t know what it would mean for his career, admitting, “I didn’t know anything about the DH.” The experiment turned out beautifully for Cepeda, who played in 142 games that season – the penultimate in a 17-year Major League career. The A’s had released Cepeda just months after acquiring him from Atlanta on June 29, 1972.

Cepeda was feted at Fenway Park on May 8, 2013, for a ceremony honoring his role as designated hitter. The Red Sox invited him to their first home series of the season, but his former Giants franchise honored the reigning World Series champion at the same time.

“It means a lot,” Cepeda said at the time. “Amazing. When you think everything is done, it’s just the beginning.”

He said that Charlie Finley, A’s owner at the time, sent him a telegram to call him within 24 hours or he would be released. Cepeda failed to meet the deadline and was fired in December 1972. He played in just three games for Oakland after the A’s acquired him from pitcher Denny McLain. Cepeda was placed on the disabled list with a left knee injury. He underwent a total of ten knee surgeries, which kept him sidelined for four different years.

Cepeda had been a first baseman and outfielder before joining baseball’s first class of designated hitters under the new American League rule.

“They talked about only doing it for three years,” he said. “And people are still not happy with the idea of the DH. They said it wouldn’t last.”

The addition of the DH opened up new opportunities for players like Cepeda and others of his era, who could still perform at the plate late in their careers, but were no longer playing the field with the perfect defense of their firsts.

Cepeda was happy that he got another chance.

He hit .289 with 20 home runs and 86 RBIs in 1973, and started strong with a .333 average and five home runs in April. He drove in 23 runs en route to DH of the Year honors in August. On August 8 in Kansas City, Cepeda hit four doubles.

“That was one of the best years,” Cepeda remembers, “because I played on one leg and hit .289. And I hit four doubles in one game. Both my knees hurt and I was named batsman of the year.”

Cepeda led Baltimore’s Tommy Davis (.306, seven home runs, 89 RBIs) and Minnesota’s Tony Oliva (.291, 16 HRs, 92 RBIs) for top DH honors.

“It wasn’t easy for me to win the award,” Cepeda said. “They had great years.”

Cepeda also knew little English when he arrived in the minor leagues in the mid-1950s, making him one of the first wave of Spanish-speaking players who found themselves in a different culture to play professional baseball, build new lives and send money home.

It was an opportunity to succeed in the sport he loved, as long as the big challenges off the field could be overcome.

Early on, Cepeda was told by a manager to go home to Puerto Rico and learn English before returning to his career in the US.

“When I came here my first year, everything was new to me, a surprise,” Cepeda recalled in a 2014 interview with the AP. “When I came to Virginia, I was there a month and my father died. My dad said, ‘I want to see my son play pro ball,’ and he died the day before I played my first game in Virginia.

“From there I went to Puerto Rico and when I came back here I had to come back because we had no money and my mother said, ‘You have to go back and send me money, we don’t have any. have money to eat,” he said.

Cepeda continued to be encouraged to see so many young players from Latin America arrive in the United States with better English skills, thanks in large part to the fact that all thirty Major League organizations were placing greater emphasis on such training through academies in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela.

English classes are also offered to young players during spring training and beyond, plus through the various levels of the minor leagues.

He also had his problems.

Cepeda was arrested in May 2007 after being stopped for speeding when officers discovered drugs in the car.

The California Highway Patrol officer arrested Cepeda after finding a “usable” amount of a white powder substance believed to be methamphetamine or cocaine, while marijuana and a syringe were also discovered.

After his playing career ended, Cepeda was convicted of marijuana smuggling in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1976 and sentenced to five years in prison.

That conviction was likely one of the reasons he was not elected to the Hall of Fame by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. Cepeda was finally elected by the Veterans Committee in 1999.

Cepeda played first base during his 17 seasons in the Majors, starting with the Giants. He also spent time in St. Louis, Atlanta, Oakland, Boston and Kansas City. In the spring of 1969, Cepeda was traded by the Cardinals to the Braves for Joe Torre.

A seven-time All-Star who played in three World Series, Cepeda was NL Rookie of the Year with San Francisco in 1958 and NL MVP in 1967 with St. Louis, a city sad to see him leave in that trade that brought Torre to village. In 1961, Cepeda led the NL with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs. Cepeda was a career .297 hitter with 379 home runs.

It wasn’t until after that season as a DH in 1973 that Cepeda was able to look back and appreciate what he accomplished that year – along with the huge role he played in the history and change in the sport.

“I just did it,” he said of learning the DH. “Every day I say to myself: how lucky I am to have been born with the skills to play with the ball.”

APMLB: https://apnews.com/hub/mlb