Health

People of West African descent are at greater risk for cardiac amyloidosis

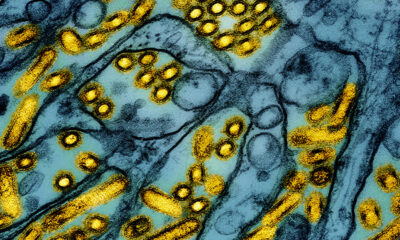

among Cardiologists know that transthyretin causes cardiac amyloidosis, a type of heart disease, by the misfolding of a protein called transthyretin, which builds up in the walls of the heart, causing the muscle to thicken and stiffen. One reason this can happen is because of a genetic mutation caused by the V142I gene variant, which is common in people of West African descent. In a new study published Sunday in the Journal of the American Medical Associationresearchers found that the 3%-4% of self-identified black individuals who carried this variant had an increased risk of heart failure and death.

Heart failure affects African Americans almost double the rate that it affects white people in the US – and the reason may be partly due to ancestry, not race. But while the link between V142I and heart failure is well known, researchers did not know how the variant affects the risk of heart failure in humans and its association with preserved heart function. Previously, researchers studied patients who already had the disease and came for treatment. In this study, researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Duke University School of Medicine looked at the natural history of the disease using data from four US National Institutes of Health-funded studies. Their findings suggest an opportunity to provide more genetic counseling. and screening for African Americans.

Notably, these studies were not designed to look specifically at amyloid heart disease, but to obtain genotyping data in healthy women and individuals with various risk factors, such as stroke and atherosclerosis.

“It would inform us, doctors and patients, of the likelihood that an individual with this genetic mutation could develop this disease at some point in their life. And the reason this is becoming increasingly important is that there are now a number of therapies available that have been available for the first time, really only in the last few years, that are available for amyloid heart disease,” said Scott Solomon, senior author of the paper and professor. in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Using this large data set, the researchers analyzed data from 23,338 self-reported black individuals, 754 of whom, or just over 3% of them, carried the V142I variant. They found that the genetic variant increased the risk of hospitalization for heart failure at age 63 and the risk of death at age 72.

“That’s sooner than we thought,” said Senthil Selvaraj, the paper’s first author and an advanced physician-scientist in heart failure at Duke University School of Medicine. Previously, researchers thought the risk of hospitalization occurred in the 1970s.

He added that they found that men and women also have a similar risk of disease, suggesting that women are quite likely to be underdiagnosed with this form of amyloid heart disease. Women generally have less thick walls, meaning that even though amyloid heart disease makes the walls thicker, it can still be missed. The researchers were also unable to determine among people who had the variant whether they had been hospitalized because of the condition or another risk factor or combination of risk factors, such as high blood pressure or diabetes.

The researchers also looked at the burden this mutation has on a person’s lifespan. On average, people who are carriers of the variant live two to two and a half years shorter than people who are not carriers. About 13 million Black Americans are over the age of 50, and researchers estimate that nearly half a million people over 50 carry the variant. “This means that today’s population of Black Americans will live about a million years less because of the variant,” Selvaraj said. According to the newspaper, that could even be a conservative estimate editorial published with the study authored by Clyde Yancy, professor and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University Feinberg School and Medicine and deputy editor for JAMA Cardiology.

Yet the implications for screening and genetic counseling are not clear. Although this variant is found in people with West African ancestry, the increased risk of heart failure and death doesn’t just affect people who identify as black.

“This kind of work is incredibly important because we must accept the clear truth that we as scientists understand: race does not lead to biology. Period of time. Difficult to stop. No modifiers, no adjectives. Race is a social variable, related to culture, to experiences, but not to biology. Period,” Yancy told STAT. The color of your skin does not protect you against this variant. He gave an example of a “delightful” white patient in his care who is currently being treated for amyloid heart disease and has the V1421 gene.

Selvaraj acknowledged that since the variant is found in people of West African descent, this is a global disease and people from different ethnic backgrounds can also carry the variant.

It’s impossible to know the global burden of disease, “but in some ways this is kind of the tip of the iceberg,” Selvaraj said.

“I think it was a well-done study,” said Evan Kransdorf, assistant professor of cardiology and member of the cardiogenetics team at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles, who was not part of the study. In addition to increasing screening, he said there is also an opportunity to pursue other areas of research. “We would like to know how the treatment would influence and change the outcome, but that is obviously a completely different study and may be difficult as there have been many rapid advances in the treatment of amyloidosis in recent years. ” One treatment is the drug tafamidis, which prevents the misfolding of the protein transthyretin. A gene editing therapy is currently in clinical trials.

Yancy, who wrote An of the two editorials said in this investigation it is the presence of the V1421 gene itself that “gives reason to increase surveillance – not because of race, but because of detectable genetic risk variables.” Screening for the mutations should be made available to all people with an appropriate disease phenotype, he argued in his editorial. This would be a similar practice to the ‘race-agnostic’ screening for APOL1 in kidney disease.

“We need to figure out how do we get a reluctant patient cohort to agree to this kind of advanced genetic screening? First of all, it’s counseling, and then it’s genetic testing, and how do we pay for that? he said. According to Yancy’s editorial, outside of commercial payers, patients on Medicare can only get cancer screenings, and Medicaid does not cover genetic testing in most states. “It could be that these types of conversations prompt CMS to reconsider coverage decisions, wouldn’t that be a really wonderful outcome?” Yancy said.

To convince a reluctant patient, Kransdorf said education is important. “I say, ‘Hey, there’s an 80% chance that I’m not going to give you any useful information, but there’s a 20% chance that I’m going to give you very useful information.’” Keeping that information in mind can help a patient decide whether it is worth potentially confirming a genetic link to his or her disease.

As science moves toward race-agnostic research, Kransdorf believes a focus on genetics will be a big part of the development of individualized or precision medicine. “Of course we’re not quite there yet, but I think that’s true Maybe in five or 10 years we’ll start to get there.” He added that robust genetic testing should pave the way. “Actual testing will give us much more precise options to diagnose and possibly treat people. … I think we can use genetic information to get past these kinds of rough estimates.”