Finance

Professor Hugh H. Macaulay: a tribute to his centenary

Click-a-clack, click-a-clack. . ., click-a-clack.

Those were the sounds that regularly echoed through the second-floor hallway of Clemson University’s Sirrine Hall in the 1980s and before. These sounds of metal on metal could have been expected by the economists on the floor at 10:00 in the morning, with a clear message: “Time for coffee!”

The sounds came unmistakably from Professor Hugh Macaulay’s steel leg brace, which he has been wearing since he suffered a gunshot wound in France during the Second World War. He had proudly signed up for the service.

The “clickities,” combined with Hugh’s knocking on office doors, would wake up eight or more economists in the department for the treat of the day: a lively policy debate in the campus coffee shop about the latest market-control ruling from Washington. Our debates usually began when we left Sirrine for the three hundred meter walk to the ‘canteen’, so called when the students of the university were all men and all cadets.

The life of Professor Hugh H. Macaulay, professor of economics at Clemson University, would have celebrated its centennial today. Those of us who were his colleagues and friends celebrate his life as an economist and moral force in the lives of all of us, as well as in the lives of his students. Hugh remains one of the most “unforgettable characters we’ve ever met,” to paraphrase one Reader’s Digests most popular series. He is also remembered as one of the profession’s staunchest defenders of the market, always ready to criticize proposals to restrict the market process.

Professor Macaulay died of kidney cancer on October 5, 2005 at the age of 81.

* * * * *

Hugh always wore a bow tie… Always! And they were made by his wife Frances – or rather, “Pinky” to anyone who knew the Macaulay’s. She was the love of Hugh’s life, his partner, colleague and soulmate. She made the bow ties from old ties. Nothing was wasted in the Macaulay household.

Hugh had his own dress code. A while ago it might have been called “Sunday-to-meeting” attire. His hair was cut short. His face, lively. His dark eyes danced as he talked and laughed with others. If you didn’t know the significance of Victorian ways of speaking and behaving before, you would after spending time with Hugh.

The style of that time meant nothing to him. Presenting a good model to his students meant everything. In my 35 years of close observation, including occasions that might have tested Job’s patience, I can tell you that Hugh never uttered a word that would not have passed the test for My Weekly Reader.

* * * * *

Hugh Macaulay knew it well and followed Adam Smith’s words in his text Theory of moral sentiments: “You should think a lot about others and little about yourself.” He told me early in my career, when I wasn’t done with my PhD. “Bruce,” he said, “everyone you ever meet, even the janitor, will know things you don’t know. We must treat them all with great respect.”

Hugh had a sharp intellect, a never-satisfied thirst for knowledge and opportunities to discuss ideas. But there was one set of ideas that mattered above all others: Economy. At this point Hugh had, in the words of JM Clark, “an irrational passion for dispassionate rationality.”

Hugh was an economist through and through. Economics was in his DNA. And Hugh’s economics wasn’t just any old economics either. It was the Adam Smith economics of markets, price theory, trade and monetary policy. It was what we in the industry call the Old Time Religion. Hugh was an unapologetic lover of market competition and individual freedom. No, more than a lover he was an evangelist.

And was he ever any good? Whenever I had trouble with an international financial problem, which happened quite often, I went to Hugh. He started by laying out principles, then moved on to their application, and before you knew it, the answer was clearly revealed, sprinkled with that familiar Macaulay humor.

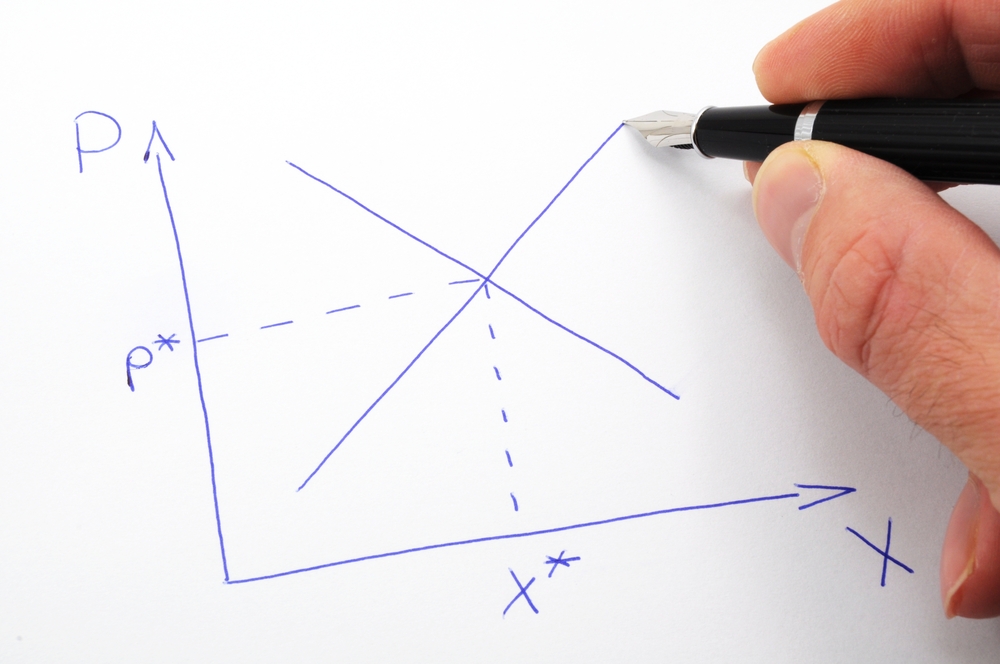

Having coffee with Hugh was great fun and could be hilarious, but the coffee discussions were serious business. Always, alwaysHugh brought a pen and notepad. If no one else came up with a question, Hugh would ask his own question, followed by drawing supply and demand curves. Our discussions could be boisterous, but were always good-natured and peppered with laughter. We all learned from the master and tried to imitate him.

Those who enjoyed Hugh’s company in our book club discussions knew what to expect if anyone even suggested that a government solution to an economic problem would be more effective than the market. Hugh then asked in a disappointed tone, “Haven’t you been listening?” And just to make sure we remembered, he persisted, often citing his favorite authorities, starting with Adam Smith, moving on to Milton Friedman, then to Ronald Coase, and finally ending with Will and Arial Durant – with he incorporated their works into a fully integrated whole. classical liberal thinking.

* * * * *

Hugh was an economist, but not just any economist. At heart, Hugh was a teacher. A research teacher. A life teacher. He was born to be in the classroom… and he knew it.

Are students? They were the joy of his life. His door was always open…, just like his house. The number of times Hugh and Pinky had students in their home were countless, and even though he was a demanding evaluator, he left his students captivated by his lectures and his thoughtfulness in helping them understand why and how he thought as he did. . Understandably, a large number of his students left his classes saying with conviction, “I would rather take another Macaulay course and get a D than take someone else’s course and get an A.”

For many, Hugh was the one who set them on a new path by writing personal and detailed letters nominating them for college or a job, and who later left a note of congratulations when they were honored in their work. Long after Hugh’s retirement in 1980, his Clemson colleagues were often asked, “And how is Professor Macaulay doing”?

In the words of one of Hugh’s former students: ‘You know, there’s really no need now to say good things about Professor Hugh Macaulay to those who followed in his footsteps and were helped by the time he gave to them and to their spent papers. . His goodness was self-evident in the way he lived his life and in the way he treated others with respect and courtesy.” At the same time, those of us who knew him feel compelled to announce forcefully on this day of celebration that every economic department needs a Hugh Macaulay, someone who will commit himself in word and deed to the essential wisdom that Adam Smith possessed in both his interdependent masterpieces, The welfare of nations, And The theory of moral sentiments.

* * * * *

I came by to see Hugh while he was in the hospital and during his last days, if not hours. Still sedated from the surgery, Hugh didn’t appear to be fully awake. Still, Pinky insisted that I come in and talk to him.

“Hugh,” I said, “I’m here to tell you that markets work.” This completely excited him. “Thanks for telling me, Bruce,” he replied. “I thought that might be the case. Now that I know for sure, I can just go ahead and die in peace. With that he burst out with that famous Macaulay laugh. Pinky and I laughed too.

Hugh Macaulay was a wonderful person.

Bruce Yandle is co-founder of the Clemson Institute for the Study of Capitalism

and Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Department of Economics and distinguished Mercatus Center adjunct professor of economics at George Mason University. He specializes in public choice, regulation and free market environmentalism.