Health

Regular mammograms should start at age 40, the national group says

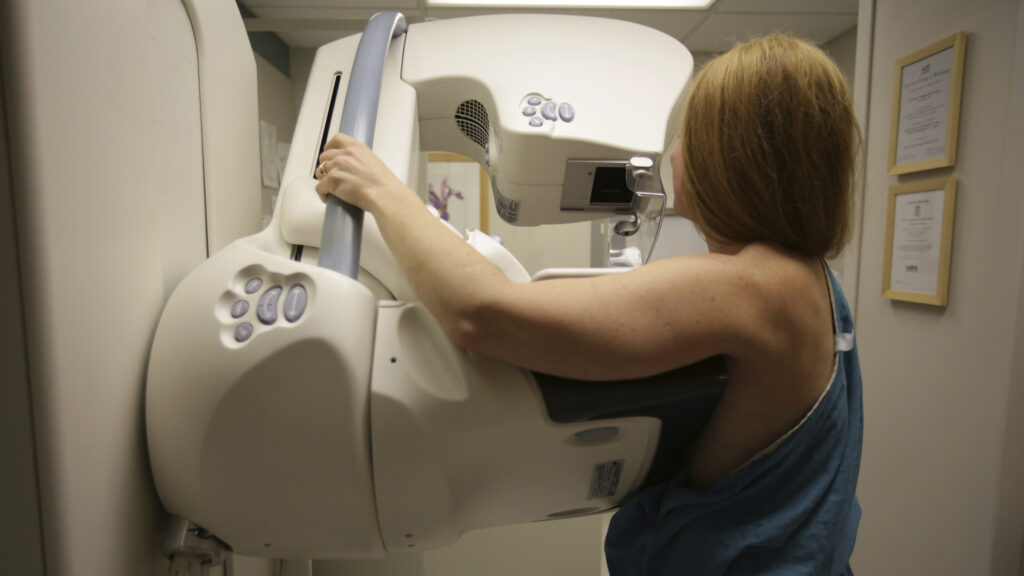

a The national advisory panel on Tuesday significantly lowered age recommendations for screening mammography, saying all women should begin breast cancer screening at age 40 instead of age 50, and continue every two years until age 74.

The panel’s previous recommendations, the United States Preventive Services Task Force, suggested that women between the ages of 40 and 49 should make an individual choice about having mammograms.

The new guidelines, first published last year as a draft open to public comment, are prompted in part by concerns about rising rates of breast cancer among younger women.

“More and more women in their 40s are developing breast cancer,” said John Wong, one of the task force members and a professor of medicine at Tufts University. “That is an increase of 2% per year between 2015 and 2019. This means that screening provides more benefits because the risk of developing breast cancer is greater.”

The changes, published Tuesday in JAMA, also to better align the task force with the guidelines of other health organizations. The American Cancer Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and others have published guidelines suggesting that average-risk women consider starting screening at age 40 or 45. But the task force’s recommendations generally carry more weight, in part because the Affordable Care Act requires health insurers to fully cover the task force’s recommendations with a grade of B or higher.

For breast cancer experts, the bottom line is that organizations that issue screening guidelines come to a consensus that starting breast cancer screening before age 50 is reasonable and will hopefully lead to “less confusion among women about breast cancer screening,” says Janie Lee, one of the researchers. breast imaging radiologist at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. “The scientific evidence is clear that mammography saves lives.”

Cancer screening recommendations generally weigh the benefits of detecting cancer early against the potential harms. Such harms include unnecessary biopsies for false-positive cases and overdiagnoses – diagnoses of tumors that grow so slowly that they would not have harmed or killed the patient before they died of something else. More screening, such as expanding the age range eligible for screening, often helps save lives, but comes at the cost of additional harm.

In this case, the task force, a rotating group of volunteer experts, believed that lowering the screening age to 40 instead of 50 was well worth the trade-off. Overall, starting screening at age 40 should translate into roughly doubling the years of life gained by catching cancer earlier, because these individuals are younger to begin with, Wong said. It should also save another 1.3 lives per 1,000 individuals, according to the statistical modeling the task force used to inform the recommendations, Wong said.

Particularly for black women, who are more likely to develop breast cancer at a younger age and be diagnosed with more aggressive tumors, that rises to 1.8 lives saved for every 1,000. That offers some hope that lowering the screening age will help reduce health disparities for racial groups that have long disproportionately suffered from breast cancer mortality and morbidity.

“This is an important step in reducing mortality and helping Black women live longer, but it is not enough to address the health inequities Black women face,” Wong said. “We recognize that it is not necessarily the screening, but perhaps also what happens after the screening. We ask health professionals to ensure that follow-up tests are performed appropriately and in a timely manner after a positive mammogram and if breast cancer is discovered.”

But one cost of lowering the screening age is 500 additional false-positive findings per 1,000 from mammography, Wong said. “In the context of the 1.3 women who were saved, we felt comfortable with that balance of benefits and harms.”

For the most part, breast cancer researchers and doctors seem to agree that it’s a good idea to start screening earlier than age 50. “I think it’s a good thing that the task force has embraced the values of screening women under 50,” said Robert Smith, vice president of early cancer detection science at the American Cancer Society.

Experts disagree on the exact details. For example, the ACS suggests that women begin screening at age 45 and make a shared decision with their trusted health care provider before then. Smith also said screening could benefit people over 75, depending on their health status, although the task force found there wasn’t enough evidence to recommend that. The task force also wasn’t convinced it was worth recommending annual screening, even though that’s what the American College of Radiology suggests.

These recommendations are generally intended for people at “medium risk.” Specifically, this concerns people who have been assigned female from the age of 40 and who do not have very high-risk mutations such as BRCA 1 or 2, who have no history of cancer, or who have had a biopsy or biopsy in the past had. lesion that showed high risk. But even among the group targeted for screening recommendations, each person’s individual risk of cancer can still be variable.

Whether you have a family history of cancer, dense breasts, certain genetic mutations, smoke or drink alcohol, or even work a certain profession, all of these factors can influence your personal risk of cancer. Scientists hope that these factors will one day help formulate personalized recommendations for when and how often each individual should be screened. Studies are underway to better understand this – although they are not yet at the point where they can be included in broad population guidelines.

“We are definitely moving away from ‘one size fits all’ recommendations,” said Lee of the University of Washington. “Breast cancer screening recommendations that are tailored to an individual’s characteristics, as well as their own preferences about weighing benefits and harms, are important. The most difficult part is the time it takes to design, conduct and report clinical trials that provide new evidence needed to update the guidelines.”

There are calculators available from organizations such as the National Cancer Institute that already provide some estimate of people’s individual breast cancer risk, added Douglas Marks, a medical oncologist at NYU Perlmutter Cancer Center. Patients are free to use such calculators, Marks said, and he feels comfortable talking to their doctors about the results.

“These guidelines should be taken to increase our global understanding of how some women at normal risk should be monitored. But individual patients must be assessed individually,” he said.