Health

Research shows that more black Americans are dying from the effects of air pollution

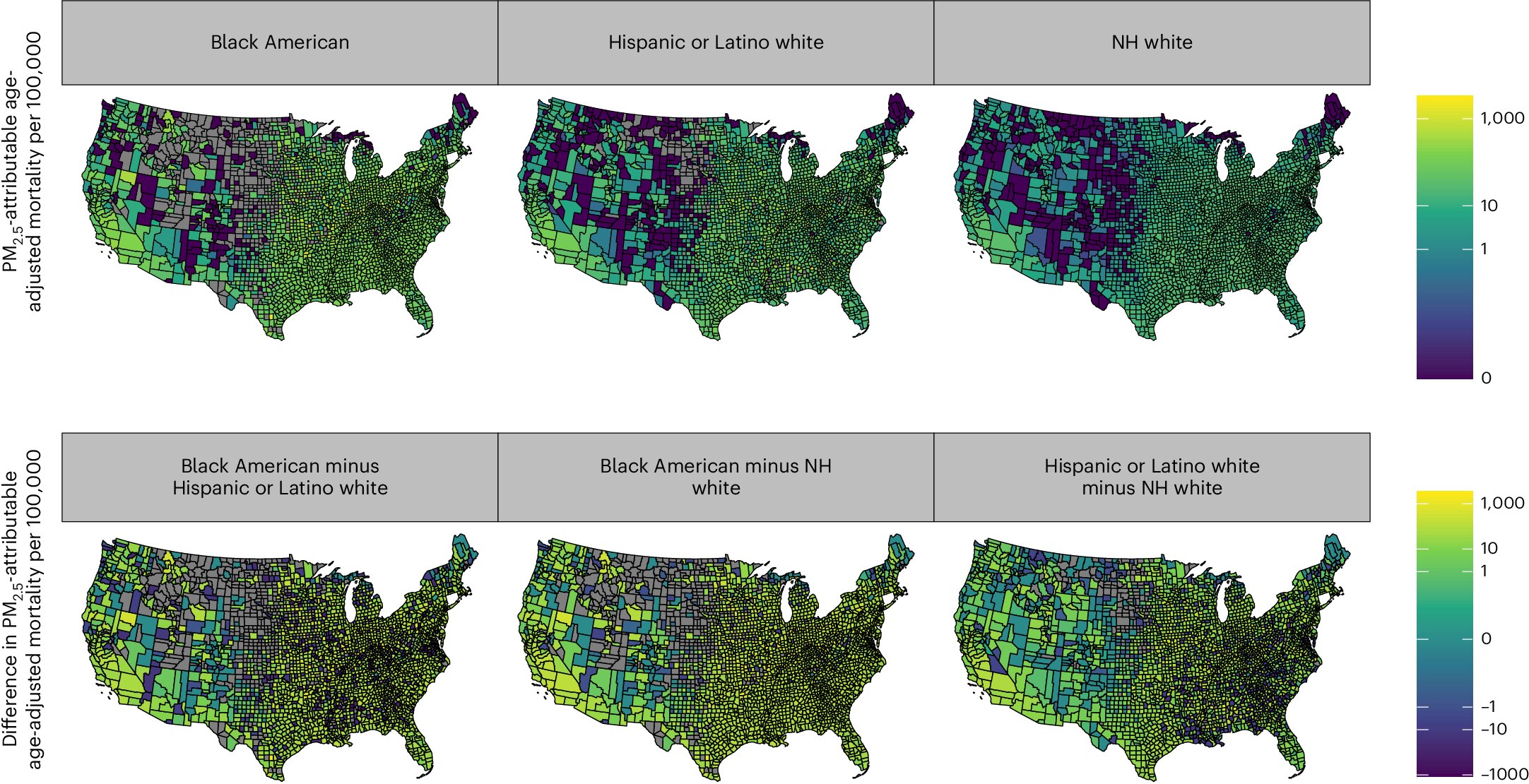

Differences in age-adjusted PM2.5-attributable mortality rate by race/ethnicity at the county level for the period 2000 to 2016. Credit: Naturopathy (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03117-0

Everyone knows that air pollution is bad for your health, but how bad depends a lot on who you are. People of different races and ethnicities, education levels, locations and socio-economic situations are often exposed to varying degrees of air pollution. Even at the same exposure levels, people’s ability to cope with their effects (for example, by accessing timely healthcare) varies.

A new study from Stanford Medicine researchers and collaborators, which takes into account both exposure to air pollution and susceptibility to its harms, has found that Black Americans are significantly more likely to die from causes related to air pollution , compared to other racial and ethnic groups.

They face a double jeopardy: increased exposure to polluted air and greater susceptibility to adverse health consequences due to social disadvantages.

“We see differences across all the factors we examine, such as education, geography and social vulnerability, but what is striking is that the differences between racial-ethnic groups – partly as a result of our methodology – are substantially greater than for any of these other factors. ,” said Pascal Geldsetzer, MD, Ph.D., assistant professor of medicine and lead author of the study published July 1st Naturopathy.

The results show how air pollution can cause health inequalities and contribute significantly to the difference in mortality rates between different groups.

But for the same reason, the researchers say that reducing air pollution could be a powerful and achievable way to tackle these inequities.

Fine particles

Air quality in the U.S. has improved dramatically in recent decades, thanks in large part to regulations such as the Clean Air Act, which places limits on air pollutants emitted by industries and other sources.

One of the pollutants most closely linked to health, and the focus of the new study, is particulate matter, also called PM.2.5 because it contains particles with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers. These particles are small enough to enter the bloodstream and affect vital organs.

‘It is very well known that Prime Minister2.5 is the biggest environmental killer worldwide,” said Tarik Benmarhnia, Ph.D., associate professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego and senior author of the study.

Exposure to these fine particles can worsen asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the short term, and contribute to heart disease, dementia, stroke and cancer in the long term.

In 1990, 85.9% of the US population was exposed to average PM2.5 levels above 12 micrograms per cubic meter – the threshold set by the Environmental Protection Agency. In 2016, only 0.9% of the population was exposed to average levels above the threshold. (In February, the agency lowered the limit to 9 micrograms per cubic meter.)

Despite these significant improvements, not all communities have benefited equally.

The benefits may vary

In the new study, the researchers wanted to see how much PM2.5 levels contributed to mortality among people of different races and ethnicities, education level, location (metropolitan or rural), and socioeconomic status.

They used existing data on county-level mortality, along with census-level data on PM2.5 air pollution and population density from 1990 to 2016. They used models derived from previous epidemiological studies, known as concentration-response functions, which linked certain deaths to air pollution levels. They chose a model that took into account differences in sensitivity between racial and ethnic groups.

“Concentration response functions essentially say that if you are exposed to that much more air pollution, you would expect, on average, a much greater risk of death,” Geldsetzer said.

Although deaths were related to PM2.5 Levels fell overall, with some groups remaining more affected than others. The researchers found higher PM rates2.5-attributable mortality among low-educated people; those who live in large urban areas; and those who were more socially vulnerable due to housing, poverty and other factors. People in the Mountain West states were less likely to die from PM2.5 pollution than people in other regions.

But the biggest differences emerged when researchers sorted the data by race and ethnicity.

In 1990, the Prime Minister2.5The attributable mortality rate for black Americans was roughly 350 deaths per 100,000 people, compared to less than 100 deaths per 100,000 people for each of the other races. By 2016, PM2.5-attributable mortality had decreased for all groups. Black Americans experienced the largest decline, to about 50 deaths per 100,000 people, but were still the highest of any group.

These relative trends were consistent across the country. In 96.6% of counties, Black Americans had the highest PM2.5-attributable mortality.

Of all the factors the researchers considered, race was the most influential in determining the risk of mortality from air pollution. They found that Black Americans are more exposed to air pollution, and its effects on mortality are compounded by factors such as poverty, pre-existing medical conditions, more dangerous jobs, and lack of access to housing and health care.

Race and racism play a role in many of these reinforcing factors, the researchers noted.

“Racism is an upstream driver of all these components of social inequality,” Benmarhnia said.

Take action

“Air pollution is increasingly recognized in public health as a cause of adverse health consequences that are greater than people initially thought,” Geldsetzer said.

Harmful levels of PM2.5 may be unnoticeable, but experienced day after day, year after year, they contribute to disease. And climate change means more wildfires (which produce particularly toxic fine particles) combined with extreme heat, increasing health risks.

“Even today, there is a lot of resistance to efforts to reduce air pollution,” Benmarhnia said, citing the recent Supreme Court ruling against a plan to limit air pollution drifting across state lines.

Environmental policies should reduce air pollutants as much as possible, the researchers said, but should also take into account that some communities are more sensitive – something major environmental organizations are not yet doing.

The silver lining is that the groups that suffer more from increasing air pollution would also benefit more from decreasing air pollution.

For each unit of reduction of PM2.5For example, the associated mortality risk would decrease more for black Americans than for other groups, closing the racial gap.

“We want to emphasize that air pollution is a very good way to reduce health inequalities because it can be acted upon,” Benmarhnia said. “We know we can do something about air pollution.”

More information:

Pascal Geldsetzer et al., Disparities in air pollution-related mortality in the US population by race/ethnicity and sociodemographic factors, Naturopathy (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03117-0

Quote: More Black Americans Die From Effects of Air Pollution, Study Shows (2024, July 17) Retrieved July 17, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-07-black-americans-die-effects-air.html

This document is copyrighted. Except for fair dealing purposes for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.