Health

Richard Slayman had an episode of rejection of his pig kidney before leaving the hospital

TThe world’s first recipient of a kidney transplant from a genetically modified pig suffered a rejection episode last week before recovering and leaving the hospital, a doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital told STAT. But in his first few days at home in Weymouth, Massachusetts, the patient – 62-year-old Richard Slayman – showed no further signs of organ problems.

Instead, he did things he hadn’t done in over a year, like eating whatever he wanted and taking a long, hot shower.

“We couldn’t have hoped for a better outcome,” Leonardo Riella, medical director of kidney transplantation at MGH, said in an interview Friday.

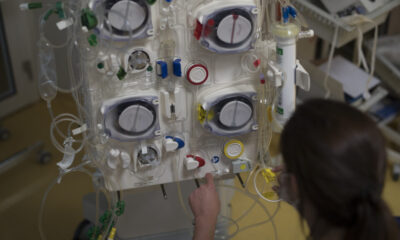

Slayman had previously undergone a human kidney transplant, but it failed after five years, forcing him to resume kidney dialysis in 2023. For the past year, he had been connected to a kidney filter machine three times a week for four hours. and was hospitalized every few weeks for complications with blood clots and other vascular problems. A catheter in his chest, intended to help alleviate these problems, made it impossible to shower.

“He was really struggling,” Riella said. “To see him leave the hospital without dialysis was one of those moments you remember for a lifetime.”

The groundbreaking procedure, performed on March 16, involved a transplant from an engineered pig kidney produced by Cambridge, Massachusetts-based eGenesis. The company is using CRISPR gene editing technology to make dozens of changes to the pig genome to produce organs that are more compatible with the human body, in an effort to solve the urgent organ shortage. This is the first test of the technology in humans, after encouraging studies in primates were published last year, and the positive outcome so far is an encouraging sign that formal trials of cross-species transplantation may not be far behind.

The pig kidney began producing urine as soon as it was surgically connected to Slayman’s circulatory system and continued to function during his first week in the hospital. Urinalysis showed that the organ filtered toxins from his blood and kept the minerals in his blood, especially potassium, in the right balance.

But on the eighth day, the kidney started showing signs of struggling. Doctors performed a biopsy and found that white blood cells began to infiltrate the transplanted organ, causing swelling and inflammation – classic signs of the most common form of acute transplant rejection, known as cellular rejection. It’s something that transplant nephrologists like Riella see in about 20% of patients who receive kidneys from human donors, and it’s treatable with high doses of steroids and a drug that depletes the body’s T cells.

Slayman’s doctors gave him these medications, and after three tense days, his body began to respond to the treatment and the function of his new kidney improved. They have also increased the immunosuppressive regimen he will be on for the foreseeable future as a precaution against future rejection episodes.

Cellular rejection can occur at any time, but especially within the first year after an organ transplant. Riella said it might actually be a good thing if it happened so quickly. “I would rather get a rejection very early and have it addressed and adjusted, than see the rejection much later, where it could go unnoticed for a few weeks, and at that point it could be too late,” he said . “It’s a bit like wildfire; you want to put it out quickly before it gets out of hand.”

MGH’s transplant team will continue to monitor Slayman with blood and urine tests three times a week and twice a week with doctor visits. They’ll look for signs of rejection and for infections – which he’s more likely to get if he’s on medications that suppress his immune system.

For the first two months, they recommend that he not return to his job as a manager at the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. And during that time, they also screen his blood weekly metagenomic sequencing technologythat picks up DNA fragments from any pathogens that may be in circulation.

“We do this passive surveillance to look for things that he might be picking up from the outside world, or transmission coming from the donor,” Riella said. The genomes of eGenesis pigs have been modified to eliminate the risk that they could pass on pig viruses to humans, a concern that has kept the xenotransplantation field frozen for most of the 2000s.

But regulators in the US remain concerned about the possibility, especially after a genetically modified pig heart made by another company, Revivicor, was discovered. discovers to have been unknowingly infected with a swine virus, which may have contributed to the death of a xenotransplant patient in 2022, two months after surgery at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

So far, Slayman is doing better than the two patients who received Revivicor pig hearts at the University of Maryland – the only two other people in the world who had a genetically modified pig organ choked into them. A second patient, who underwent the procedure last September, began showing signs of organ rejection a month after surgery and died two weeks later.

Despite his patient’s progress, Riella said it is too early to begin discussions with the Food and Drug Administration about conducting a new pig kidney transplant under “compassionate use,” the regulatory route that allowed Slayman to use the organ outside of a clinical setting. to test. The transplant team of MGH and eGenesis executives are in ongoing discussions with the agency about starting a clinical trial, he said.

This story has been updated to include details of Dr. Riella to correct.