Technology

Sourdough under the microscope reveals microbes that have been cultivated for generations

This article originally appeared on The conversation.

Sourdough is the oldest type of sourdough bread in recorded history, and people have been eating it for thousands of years. The components for making a sourdough starter are very simple: flour and water. Mixing them creates a living culture in which yeast and bacteria ferment the sugars in the flour, creating byproducts that give sourdough its characteristic taste and smell. They also ensure that it rises when no other leavening agents are present.

My sourdough starter, affectionately known as the “Fosters” starter, was passed down to me from my grandparents, who received it from my grandmother’s college roommate. It has followed me across the country throughout my academic career, from my undergraduate work in New Mexico to graduate school in Pennsylvania and post-doctoral work in Washington.

Currently it is located in the Midwest where I as senior research associateworking with researchers to characterize samples in a wide range of areas ranging from food science to materials science.

As part of one of the microscopy courses I teach at university, I decided to take a closer look at the microbial community in my family’s sourdough starter with the microscope I use in my daily research.

Scanning electron microscopes

Scanning electron microscopy, or SEM, is a powerful tool that can image the surface of samples at the nanometer scale. For comparison: a human hair is between 10 and 150 micrometers, and SEM can detect features 10,000 times smaller.

Because SEM uses electrons instead of light for imaging, there are limitations to what can be imaged with the microscope. Samples must be electrically conductive and able to withstand the very low pressure in vacuum. Low-pressure environments are generally unfavorable for microbes because these conditions cause the water in the cells to evaporate, deforming their structure.

To prepare samples for SEM analysis, researchers use a method called critical point drying which carefully dries the sample to reduce unwanted artifacts and preserve fine details. The sample is then covered with a thin layer of iridium metal to make it conductive.

Exploring a sourdough starter

Because sourdough starters are made from wild yeast and bacteria in the flour, it creates a favorable environment for many types of microbes to flourish. There can be more than 20 different types yeast and 50 different types of bacteria in a sourdough starter. The most robust become the dominant species.

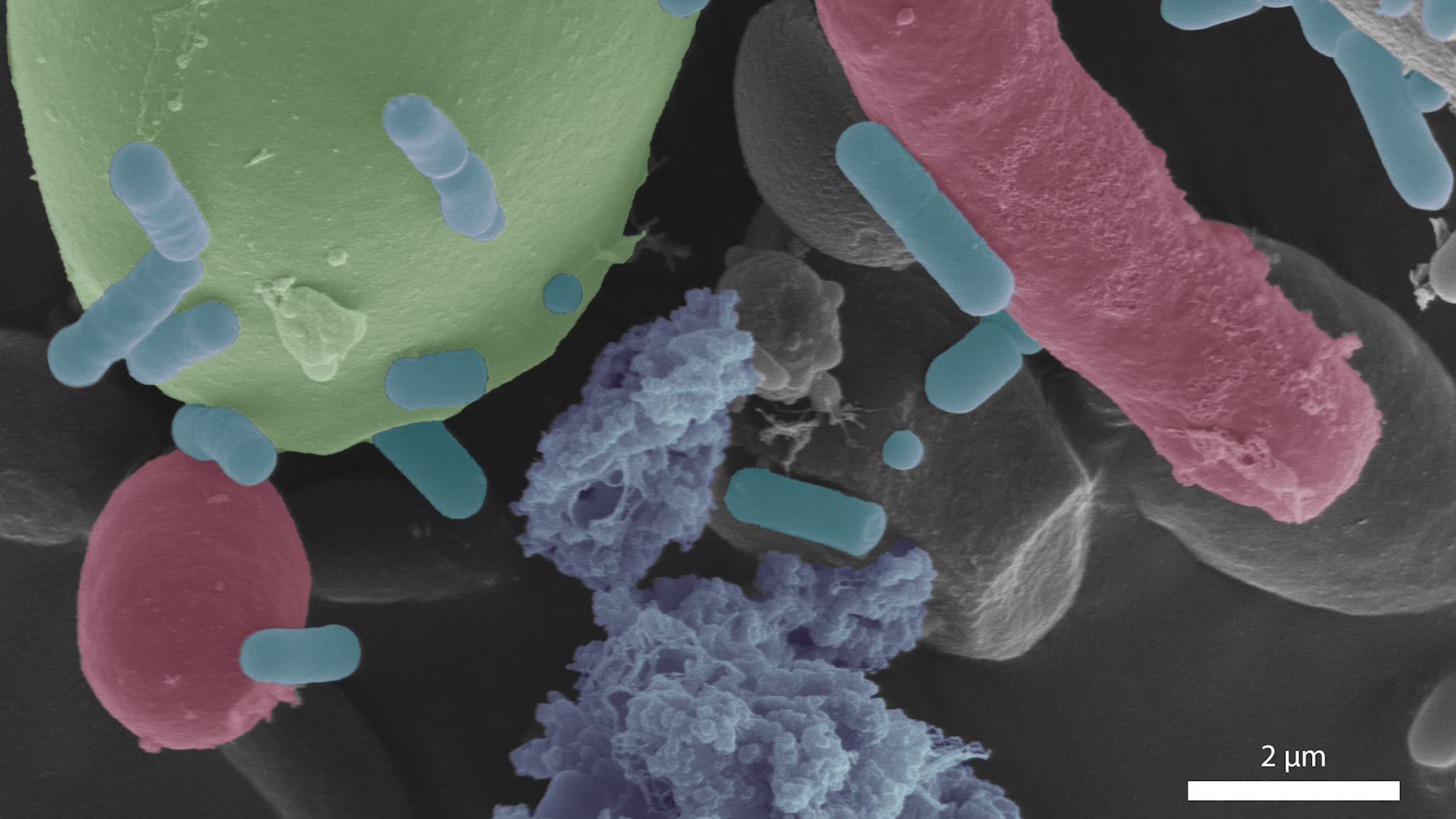

You can visually observe the microbial complexity of sourdough starter by imaging its various components that vary in size and morphology, including yeast and bacteria. However, to fully understand all the diversity present in the starter is a complete gene sequencing.

The main ingredient that gives the starter texture is starch granules from the flour. These grains, which are colored green in the image, are recognizable as relatively large spherical structures about 8 micrometers in diameter.

The yeast, which is red in color, gives rise to the starter culture. As the yeast grows, it ferments sugars from the starch grains, releasing carbon dioxide bubbles and alcohol as byproducts that leaven the dough. Yeast generally falls into the range of 2 to 10 micrometers large and are round to elongated in shape. There are two different types of yeast visible in this image: one that is almost round, lower left, and another that is elongated, upper right.

Bacteria, colored blue, metabolize sugars and release byproducts such as lactic acid and acetic acid. These by-products act as a preservative and give the starter its characteristic sour smell and taste. In this image, bacteria have pill-like shapes about 2 micrometers in size.

Next time you eat sourdough bread or sourdough waffles – try them, they are delicious! – you can visualize the rich array of microorganisms that give each piece its distinctive flavor.