Health

Testing for H5N1 bird flu in cows will be more limited than USDA has indicated

NNew federal rules aimed at limiting the spread of the H5N1 bird flu virus among dairy cattle take effect Monday, but detailed accompaniment documents Released Friday by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, it appears that the mandatory testing sequence is less stringent than initially described.

While this alleviates concerns from farmers and veterinarians about the economic and logistical burden of testing, questions remain about how effective the testing program will be in containing new outbreaks.

“More testing is better,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and director of Brown University’s Pandemic Center. “But in many ways this policy is very leaky in terms of the amount of virus it will be able to move. And because we still don’t know what’s causing transmission between cows, we shouldn’t get our hopes up that this policy will make a big dent in the infections we’re seeing.”

On Wednesday, the USDA issued a federal order requiring farms to ensure that lactating dairy cows test negative before moving them across state lines. Labs and state veterinarians must also report to the USDA any animals that have tested positive for H5N1 or another influenza A virus. The guidelines issued Friday limited the scope of that order.

It says farmers only need to test a maximum of 30 animals in a given group. The guidance does not say how farmers should determine which 30 animals to test in larger groups that are being prepared for movement. The USDA did not respond to STAT’s questions about the rationale for the 30-animal limit.

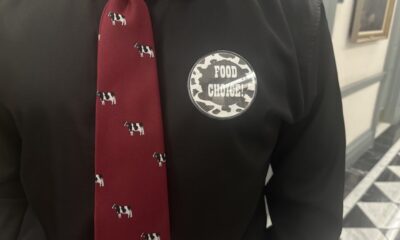

Jamie Jonker, chief scientific officer of the National Milk Producers Federation, said the group supports the testing program as an important step in response to the outbreak, a step that dairy farmers are prepared to take “as part of their responsibility to ensure the safety of their products to ensure”. animals and the milk supply.”

Although pragmatic, researchers who spoke to STAT were divided on whether the policy will be effective. Anice Lowen, a flu researcher at Emory University School of Medicine, told STAT via email that the approach is likely sufficient to detect an H5N1-positive herd. “I think this approach is reasonable,” she said.

However, Nuzzo was concerned that in very large herds, such as those of about 500 or more, infected animals could be missed. In herds where outbreaks have occurred, only somewhere between 5% and 15% of cows have shown clinical signs, Terry Lehenbauer, bovine disease epidemiologist and director of the Veterinary Medicine Teaching and Research Center at UC Davis, told STAT. “My general experience suggests there aren’t many lactating cattle that are regularly moved interstate, so we’re probably looking at quite small numbers of animals that will be needed,” he said.

The federal order acknowledges epidemiological evidence that the virus is spreading between cows in affected herds and between herds as cattle are moved. Outbreaks of H5N1 have been confirmed since April 26 34 dairy herds in nine stateswith the first outbreak reported Friday in Colorado.

But analysis of viral genomes from cows infected with H5N1, combined with evidence that genetic traces of the virus have been commonly found in milk in supermarkets, indicate the outbreak is much more widespread.

The risk of infection from ingesting milk is believed to be very low because pasteurization should kill the virus. Academic researchers found no live virus in a small study of commercial milk products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is conducting its own, much larger study of the viability of the virus in milk, with results expected in the coming days. On Friday, the FDA issued an update stating that multiple tests have been conducted samples of powdered infant and toddler food were negative, indicating no H5N1 viral fragments or whole virus present. No details were provided on the quantity tested.

Because farmers are required to remove milk from sick animals from the national food supply, traces of H5N1 in supermarket products indicate that asymptomatic animals can also shed the virus. In a frequently asked question Posted online Thursday, the USDA confirmed that cows without signs of illness can still test positive for the virus, acknowledging that H5N1 had been found in the lungs of an asymptomatic cow in an affected herd.

As per the new rules, cows transported between states must be sampled and tested at least a week before transport. A licensed or accredited veterinarian must collect the samples: between 3 and 10 milliliters of milk per animal from each of the four teats. That’s very important, the USDA noted, because there have been reports of infected animals having the virus in only one teat.

One strange feature of H5N1’s jump from birds to cows is that the virus appears to have developed an affinity for breast tissue. Samples from sick cows show the highest levels of virus not in their noses but in their milk, indicating that the udders appear to be where H5N1 migrates to or infects.

The USDA order does not apply to beef cattle or non-lactating dairy cattle, including calves, due to their lower risk profile, according to the guidelines. But flu researchers told STAT that not enough is known yet about the risks to non-lactating animals to discount them. “Testing such livestock intended for interstate movement would not only protect against interstate spread of the virus, it would also provide important insight into the susceptibility of non-lactating animals,” Lowen said.

Thijs Kiuken, professor of comparative pathology at the Department of Virosciences at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, is particularly concerned about the possibility that milk from infected cows could harm calves. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has encouraged farmers to throw away milk from H5N1-positive cows, but if that’s not possible and farmers plan to feed calves that milk, they should heat it first to kill any viruses and bacteria.

Newborn calves need to consume colostrum, the antibody-rich milk that cows produce in the first few days after birth, to build their immune systems to ward off any microbial threats on a farm. Without this, calves often quickly succumb to infections.

If a farmer does not know that a cow has H5N1 because it shows no symptoms, calves can inadvertently ingest the virus. The reason Kiuken is concerned is because of a cluster of fatal H5N1 cases in baby goats reported in Minnesota in March. Genomic analyzes showed they likely contracted the virus from a backyard poultry flock that was depopulated days before the goats were born due to H5N1. The animals had shared the same space, including a water source that was likely contaminated. According to a reports the USDA to the World Organization for Animal Healthfive goats died from multi-organ diseases, including neurological symptoms, and the virus was later found in the brains of some animals.

“Since we don’t know the extent of this virus in dairy herds in North America,” Kiuken said, “I would expect neurologically affected calves to emerge at some point. My prediction is that, if it has not already happened, young dairy calves on the affected farms will be found with severe, highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 infection.”

At this time, there have been no reported cases of H5N1-positive dairy cattle showing signs of neurological disease in the US.

Helen Branswell contributed reporting.