Finance

The anti-China roots of US government policy

Today, residential zoning, drug prohibition, and restrictions on legal immigration are three of America’s most consequential public policies. As we’ll see, all three started in California, and all three were explicitly motivated by extreme anti-China bigotry. All three policy measures were intended to exclude ‘undesirables’.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that modern proponents of these policies have a similar motivation, although I will argue that bigotry continues to play a role in at least some of these policies.

Until recently, I had assumed that these three policy regimes began at the turn of the twentieth century, as part of the so-called “progressive era” of activist governance. In fact, they started in the late 19th century, mainly in California. A recent one Jacob Sullum article in Reason magazine examined this period:

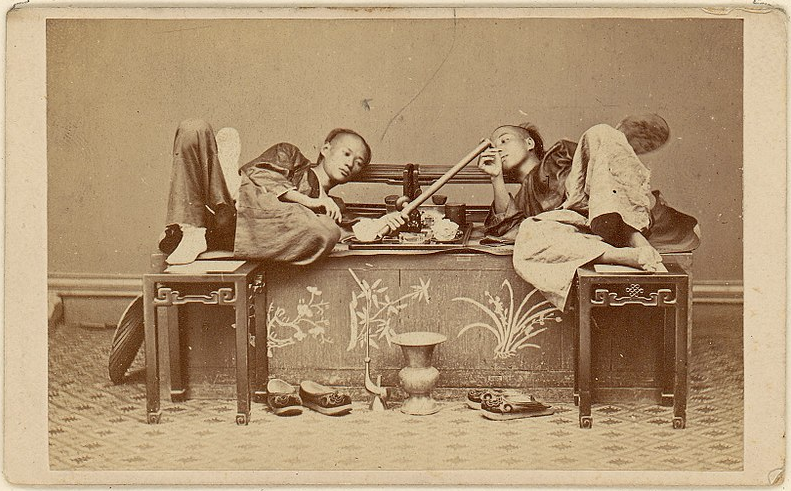

‘Smoking opium is not our vice’

America’s first drug war was driven by xenophobia against Chinese migrants

Despite the title, the article is about much more than the war on drugs; it shows how deep-seated racial prejudices influenced a wide range of government policies.

Much of the article focuses on San Francisco’s infamous opium dens, which led to the first U.S. laws banning drug use:

These ‘notorious resorts’ were ‘an outright evil’ and demanded ‘immediate and strict legislation’. . . . That “rigid legislation” was the nation’s first anti-drug law, if you don’t count the short-lived alcohol bans that thirteen states passed in the mid-1800s.

Of course, this war on drugs was unsuccessful:

Wasn’t San Francisco’s ban supposed to put an end to that? Despite the 1875 ordinance, Rogers reported in 1876, “the practice, deeply entrenched, still continues.” And “in enforcing the law in relation to this matter,” police have found “white women and Chinese side by side under the effects of this drug – a humiliating sight for anyone with any semblance of manhood left.” That comment reflected concerns about miscegenation promoted by opium, including fears that Chinese men were using the drug to seduce or sexually enslave white women.

Incidentally, the fear of miscegenation remains a common theme in the war on drugs, as illustrated in the 2000 Soderbergh film entitled Traffic. [Full disclosure: My wife is Chinese, so perhaps I have “nothing left of manhood”.]

The ultimate goal was to get Chinese residents to leave the country:

In the eyes of politicians like Lewis, the opium problem was inextricably intertwined with the Chinese problem. If the government could not remove these “filthy” foreigners by force, as Lewis seemed to prefer, it could at least make life as difficult as possible for them. As former Congressman James Budd put it at an 1885 anti-Chinese rally in Stockton, California, it was the “duty” of local authorities to make conditions so “diabolically uncomfortable” that the Chinese would be “glad to leave.” .

Lawmakers certainly tried. San Francisco’s ban on opium dens, which cities like Stockton imitated, was just one facet of a broad, long-running legal campaign aimed at subjugating or expelling Chinese immigrants. In addition to efforts to completely ban Chinese immigration to California, that campaign included special taxes, discriminatory regulations, and restrictions on the rights to hunt, fish, own land, vote, and testify in court.

Judges often allowed these types of laws, despite their clear discriminatory intentions:

“Smoking opium is not our vice,” wrote U.S. District Judge Matthew Deady, “and therefore this legislation may proceed more from a desire to torment and annoy the ‘heathen Chinese’ in this respect than to protect people from the bad habit. But the motives of legislators cannot be the subject of judicial investigation with the aim of affecting the validity of their actions.”

In other cases, the laws were deemed too intrusive and blocked by judges who held views that seem almost strangely old-fashioned in 2024:

“The prohibition of vice is not normally within the police power of the state,” [Justice Jackson] Temple wrote. “A crime is a violation of some right, public or private. The purpose of the police force is to protect rights from the attacks of others, not to banish sin from the world or to make people moral… Such legislation is very rare in this country. There seems to be an instinctive and universal feeling that this is a dangerous province to enter, and that by such laws individual liberty may be very much restricted.” The concurring judge A. Van R. Paterson also argued that “every man has the right to eat, drink and smoke whatever he wants in his own home, without the intervention of the police.”

Today, American politicians continue to blame the Chinese for corrupting our youth. China is said to be responsible for America’s fentanyl epidemic – as if we have no say in it. Not because China exports fentanyl to America, nor because they export fentanyl to Mexico which is then exported back to America. They are more likely to be blamed for exports chemicals that can be used elsewhere to make fentanyl. As viewers of Break bad We are well aware that Americans are quite capable of making illegal drugs without any help from the Chinese. And prison sentences have generally been longer for drugs favored by African Americans (crack cocaine) compared to drugs favored by white Americans (powder cocaine). Racial prejudice has always been a factor in the war on drugs.

In 1909, the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act banned the importation of opium (other than for medicinal purposes). But even in the early twentieth century, some politicians saw the folly of assuming that a ban on opium imports would solve the problem:

Although “Chinese people long for opium prepared for smoking in their own country,” said Rep. Sereno E. Payne (R-NY), smokable opium “can be manufactured in this country from medicinal opium.” And “instead of not having it at all,” he added, “they should undoubtedly prepare for it in this country.” Given that prospect, Payne was skeptical that the law would have a substantial impact on opium smoking.

Anti-Chinese sentiments also led to the very first laws aimed at restricting immigration based on national origin:

The ‘moral crusade’ championed by the Chronicle soon inspired the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first federal law to ban immigration based on national origin. The law, which applied to ‘skilled and unskilled workers’, made exceptions in principle for certain categories of visitors, but permission was difficult to obtain. Congress also made Chinese immigrants already living in the United States ineligible for citizenship and required them to obtain re-entry permits when traveling abroad. Such a policy was welcomed by the ‘Anti-China Leagues’ that began to spread in the West in the late 19th century.

Even today, some of our leading politicians protest against admitting (legal) immigrants from “s***h*** countries”, no matter how talented they are. Immigrants from poor countries like India and Nigeria have actually done quite well in America.

The 1916 residential zoning laws in New York City are widely regarded as the first example of the use of regulations to prevent “undesirables” from moving into certain neighborhoods. In fact, an even earlier example occurred in California, again motivated by anti-Chinese sentiment:

Other anti-Chinese measures from this time were neutral on the surface, but clearly targeted a specific ethnic group. For example, San Francisco instituted a minimum space requirement of 500 cubic feet per resident for private residences (banning communal living in Chinatown), banned theatrical performances between midnight and 6 a.m. (focused on Chinese opera), and required permits for laundries in Chinatown. wooden buildings – permits that Chinese laundry owners were somehow never able to obtain. The latter ordinance was approved by the California Supreme Court, which saw it as a valid exercise of the city’s police power. But the U.S. Supreme Court later unanimously ruled that the law’s discriminatory enforcement violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection.

Today, San Francisco continues to restrict the construction of low-cost housing. As a result, the area’s already fairly small African American population is being priced out, while countless “Black Lives Matter” signs populate San Francisco’s front yards. African Americans made up about 13.4% of San Francisco’s population in 1970; today the stock is down to about 5%. If “progressive” NIMBYs have their way, even that 5% will soon be gone.

To be clear, there are many people who favor drug, housing, and immigration regulations for reasons other than ethnic prejudice. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that these rules were originally put in place to exclude people considered undesirable, and that many modern Americans are still motivated by anti-Chinese prejudice. Recently, several states have introduced restrictions Chinese students attending their state schools, and also banned Chinese people from purchasing real estate. Unlike Huawei and TikTok, there is no plausible national security argument for this policy.

P.S. There is much more interesting to be found in the Sullum article; I encourage people to read the entire article. It’s also worth thinking about how perceptions change over time:

Another San Francisco police officer, George W. Duffield, who testified before the California Senate Special Committee on Chinese Immigration a year after Douglass’s raid, claimed that “ninety-nine Chinese out of a hundred smoked opium” and that “every house ” an opium den.

Even then, that was a gross exaggeration. Nowadays drug use is under Asian-Americans is significantly lower than any other ethnic group.

P.S. A recent article in The economist starts like this:

One of the most chilling moments in America’s postwar relationship with Japan occurred in Detroit in 1982. Two American auto workers beat a Chinese-American man to death, mistaking him for a Japanese citizen they accused of stealing American jobs. A sympathetic judge fined them $3,000 without jail time. This scandalously lenient verdict reflected a mood that later extended to the highest levels of government. Fearing being overtaken by Japan as the world’s economic superpower, America wielded the crowbar. It imposed trade restrictions, tried to pry open Japan’s domestic markets and led international efforts to drive down the value of the dollar against the yen. Only after Japan’s asset price bubble burst in the 1990s did America leave it alone.

Sounds familiar?