Health

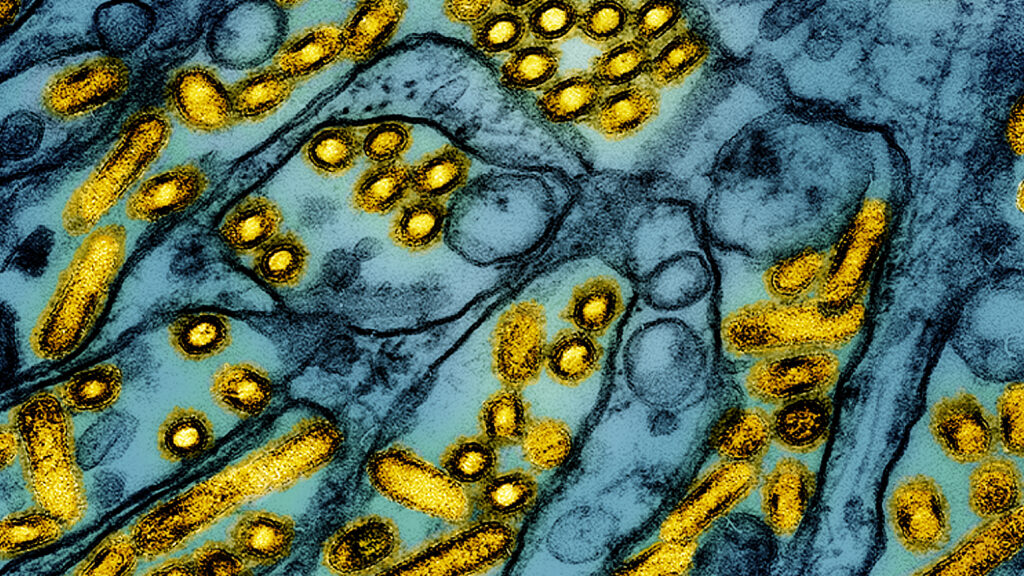

The H5N1 bird flu virus began spreading among cows in Texas in December

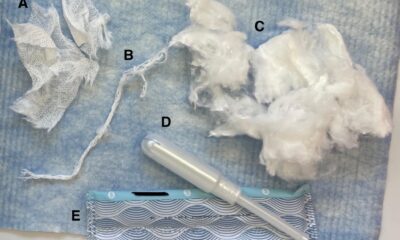

aAs agricultural authorities and epidemiologists try to understand the scope of the latest confusing chapter in the decades-long story of the H5N1 bird flu virus — its jump into U.S. dairy herds — they are turning to the genetic breadcrumbs the virus leaves behind in the nose, lungs and, most importantly, the milk of the animals.

Scientists from the US Department of Agriculture announced this on Wednesday a preprint – a study that has not yet been peer-reviewed – and which describes for the first time what their research into 220 viral genomes from infected cows has yielded so far. The study authors suggest that the spread among cattle began as a result of a single bird spillover event in the Texas Panhandle, which may have occurred in early December. The USDA did not confirm the presence of H5N1 in a Texas herd until March 25.

“These data support a single introduction of the virus of wild bird origin into livestock, likely followed by limited local circulation for approximately four months prior to confirmation by USDA,” the authors wrote.

The findings add more precision to what had previously been reported by academic scientists. Reading viral genomes can provide clues to the origins of the outbreak and allow researchers to track how the virus, which mainly infects wild and farmed birds, changes as it gains a foothold in bovine hosts.

In an initial analysis of USDA genome sequence data released last week, academic DNA sleuths had revealed that the outbreak in dairy cows has likely been going on for months longer than previously thought, and has likely spread more widely than official figures suggest . So far, the USDA has reported that 36 herds in nine states have tested positive for the virus.

The new analysis also provides insight into how bird flu changes as it spends time in the bodies of livestock.

In recent years, H5N1 has spread from wild birds to a variety of carnivorous mammals, including foxes, bears and seals, but in each of these cases the virus has hit a dead end. The outbreak in dairy cows is one of the first times that this avian flu virus has demonstrated the ability to transmit efficiently between mammals, says Thomas Mettenleiter, a virologist who was director of the Friedrich Loeffler Institute — Germany’s top animal disease research center — from 1996 until his resignation last year. The other example involved a number of outbreaks on mink farms in Spain and Finland in 2022 and 2023 respectively.

“These spillover events do not typically lead to chains of transmission,” he said. “This situation is definitely an eye-opener for me.”

The USDA’s analysis found about 20 mutations that have emerged in the H5N1 virus as it circulates among dairy cattle, which are known to make influenza viruses more deadly or more likely to infect humans.

“It is still very difficult to draw a risk map from this, but there appears to be a continuous evolution,” says Mettenleiter. “This is not surprising, but good to know. All these passages from mammal to mammal, as we would do experimentally, put an evolutionary pressure on the virus to mutate and this is what we are seeing with the increase in these known adaptation markers in mammals.”

Vivien Dugan, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s influenza division, told STAT Thursday that the mutations found so far did not raise any immediate warning signs of an increased risk to human health.

“I think this is based on our analysis of the consensus and some of that [sequence] data – because we have a good data sharing relationship with USDA – we have not seen anything at this time that would concern us about mammalian adaptation,” Dugan said.

The CDC has tested existing H5 vaccines on ferrets showed that vaccination appears to provide cross-protection against the virus from the man who was infected in Texas.

Scientists frustrated by the slow trickle of data from the USDA studies hailed the preprint on social media as progress. “I’m very grateful to this research team for sharing this, although I hope they didn’t keep the data just to ensure it’s published first,” Angela Rasmussen, a virologist who studies pathogens that jump from animals to humans at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan, in Saskatoon, Canada, posted on X on Thursday.

For weeks, the agency has faced criticism from scientists and pandemic experts over a lack of transparency and timely data sharing on the outbreak, which has slowed efforts to track its progress. When the USDA eventually uploaded a large set of genetic sequences of the pathogen to a public database, researchers eager to analyze the sequences to determine whether the H5N1 virus has changed as it is passed from cow to cow quickly discovered that the sequences didn’t. contain the necessary information about when and where the samples were collected. They are all simply labeled “USA” and “2024.”

The USDA has denied that this basic information – called metadata – was extracted from the sequence files. The agency’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has said it is sharing raw sequence data as quickly as it becomes available and plans to upload “consensus sequences,” which will be more thoroughly edited and contain the metadata scientists are looking for, as soon as they to be ready.

Helen Branswell contributed reporting.