Health

The H5N1 virus can be detected in store milk, scientists say

SScientists from the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center have managed to generate a complete genetic sequence of the H5N1 virus from milk, a development they say means commercially purchased milk products can be used to track the progress of the outbreak. to monitor bird flu in dairy cattle. and to monitor for significant changes in the virus over time.

With dairy farmers still reluctant to allow testing of their livestock, scientists trying to assess whether the outbreak is increasing or decreasing are left in the dark. Likewise, their monitoring of major changes in the viruses — changes that indicate the virus is evolving to better infect mammals — is hampered by the limited data shared by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Analyzing store-bought milk could provide a solution, University of Washington researchers and Fred Hutchinson suggested, similar to efforts underway to analyze wastewater from across the country to check for the presence of influenza A -viruses. (H5N1 is a member of that large family of flu viruses.)

“I think the most important thing is that we showed that this is possible, and that it is a good tool,” said Pavitra Roychoudhury, a research assistant professor in the department of laboratory medicine and pathology at the University of Washington School of Medicine. “And if there is resistance to having cows tested, this may be the best option. And I think this method will allow us to track variant changes over time.”

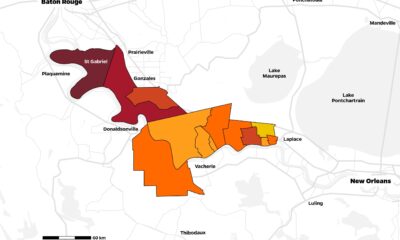

Since the H5N1 outbreak in cows was first confirmed on March 25, a total of 51 herds in nine states have tested positive for the virus. One human infection has been discovered in a Texas dairy farm worker who developed conjunctivitis.

Public health authorities and scientists believe that H5N1 is more widespread than these figures suggest, but are being hampered in their efforts to map the extent of the problem due to a lack of cooperation from dairy farmers.

Farmers are reluctant to have their livestock tested because they see no advantages and many disadvantages if it is determined that cows are infected with the bird flu virus.

A U.S. Department of Agriculture regulation that took effect April 29 requires farmers to test lactating dairy cows transported across state lines. But the rule limits the number of cows to be tested per shipment to 30, leaving the choice of which cows to test up to the individual farmer. Only fifteen new herds have been reported since the rule went into effect, leaving observers wondering whether it can have the intended effect as currently written.

“Anytime you have a regulation, someone will find a way around it,” said Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and professor of large animal internal medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Poulsen, who believes testing of milk in the bulk tanks will eventually have to happen on individual farms, agrees that monitoring milk for virus particles would provide useful data.

That includes Richard Webby, director of the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals, based at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. Webby’s laboratory was involved in early testing to see if there was evidence H5N1 RNA could be found in commercially purchased milk.

A major study conducted in mid-April by the Food and Drug Administration found that one in five milk samples brought in across 38 states was positive for the H5N1 virus. It should be noted that the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test used can detect both live viruses and fragments of dead viruses, and cannot distinguish between the two. Attempts to grow a live, infectious virus from positive milk samples have so far failed, supporting the FDA’s claim that pasteurization kills the H5N1 virus in milk.

Webby said there are some potential complications with using milk to monitor changes in H5N1; As the virus changes, it can sometimes be difficult to know what is being seen. For example, if genetic sequencing were to reveal evidence of more than one version of the virus in a sample, it may be difficult to know whether changes have been observed in, for example, the hemagglutinin and the neuraminidase proteins – the H and N in an influenza A -virus. name — appeared in all viruses, or if some had one of the changes, some had the other, and some had both.

That’s not to say the work still wouldn’t yield important data, Webby said. “The fact that viruses with those two mutations exist is useful information in itself. So I don’t want to downplay the whole idea at all. I think it’s definitely a great way to track the continued evolution of the virus. It just won’t be as clean as creating single source samples.

Peter Han, research manager of a lab run by Lea Starita of the University of Washington’s Brotman Baty Institute for Precision Medicine, said the group collected 40 milk samples by simply asking people to bring a test tube’s worth from the stash in their milk. own refrigerators. Two of the 40 were positive for H5N1 fragments and the complete genetic sequence was generated from one of those two samples. The two positive samples came from milk packaged in Colorado, where herd outbreaks have been reported.

Although it was cheap, the work was not easy, Roychoudhury said. “Milk is a very challenging sample to work with because it has a lot of fat in it,” she said. “So the fact that we were able to extract an entire genome from it was somewhat surprising to us. It also means there was enough virus in there to extract a genome, which to me was somewhat – maybe not slightly – alarming.”

The genetic sequence of the virus was uploaded to Genbank, a sequence database maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Roychoudhury said the group struggled to figure out how to date the finding — genetic sequences are typically identified by where and when the virus sample was taken, and the species or substance from which the viral information was extracted. Since there was no clear idea of when the milk was produced, the group simply identified the order by month and year.

The series is also posted on Nextstrain.orga website designed to track the evolution of pathogens such as influenza and SARS-CoV-2, which causes Covid-19.

Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist in the Division of Vaccines and Infectious Diseases at Fred Hutchinson and one of the architects of Nextstrain, said the group behind generating the genetic sequence from milk has informed the various US government agencies involved in the H5N1 response to the hopes that an organized effort can be made to use this form of surveillance.

“You could imagine a systematic effort from something like USDA — I’m not sure who exactly the right agency is — or the academic groups could work together a little more,” said Bedford, adding that he thinks milk monitoring is important can provide information that has been missing until now. up to now. “Apart from sequencing for evolution [of the virus]which I think is very important. Even understanding the prevalence in space and time I think would be very useful and important.”