Health

The number of deaths from heart failure is increasing, especially among people aged 45 or younger

Death rates for heart failure are heading in the wrong direction, a new analysis reports, reversing a decline in deaths that means more people in the United States are dying from the condition today than 25 years ago. The worrying conclusion comes as newer drugs raise hopes for better outcomes in the coming years.

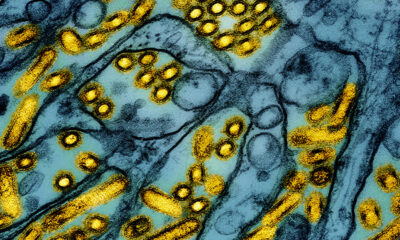

a inquiry letter published Wednesday in JAMA Cardiology tracked US death certificate data from 1999 through 2021, which showed a steady decline in deaths until 2012, when rates held steady, then began rising steadily and accelerated when the Covid-19 pandemic emerged. Disparities between men and women and between racial and ethnic groups increased in almost parallel, but there was one glaring exception: age.

The death rate for people under 45 rose by 906% between 1999 and 2021, compared to an increase of 364% for people aged 45 to 64 and 84% for people aged 65 and over.

“If we shift the obesity crisis, the liver crisis, and the diabetes crisis in the United States to younger ages, which is exactly what has happened over the last decade, the result is what we are seeing now: shifting the incidence curve from heart failure to a younger age group,” said the paper’s lead author, Marat Fudim. He is the medical director of the Heart Failure Research Unit and Heart Failure Remote Monitoring at Duke University Medical Center. “A lot of the gains, and the acceleration, would actually be attributed to the young people at that age under 45.”

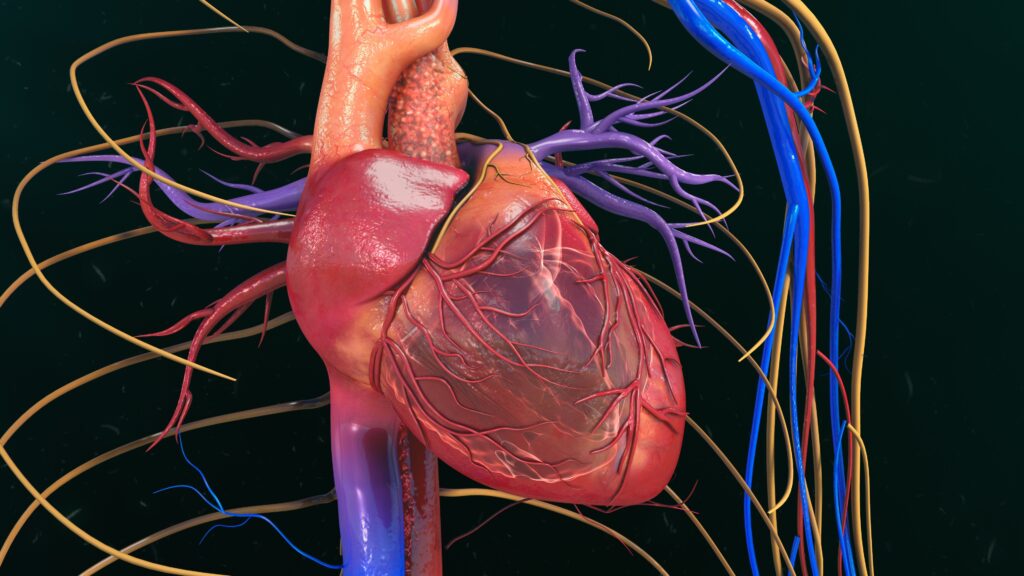

Heart failure is a chronic, progressive condition that weakens the heart’s ability to compress and then pump blood around the body. Two main types are defined by a measure called ejection fraction. When the heart relaxes after normally contracting, this is known as reduced ejection fraction; if it does not relax afterwards, it is known as preserved ejection fraction. Symptoms may be the same for both groups, roughly divided in half, but more medications are effective at treating symptoms in people with reduced rather than preserved ejection fraction.

The risk of hospitalization is greater for people with preserved ejection fraction and their quality of life is lower, often making it difficult for them to leave their home to do basic activities such as grocery shopping or even going to the mailbox. Preserved ejection fraction is often associated with cardiometabolic diseases: obesity, hypertension, diabetes, inactivity, “all those things that we know have gotten worse in recent decades,” said Sean Pinney, chief of cardiology at Mount Sinai Morningside. He was not involved in the JAMA Cardiology article. “We are seeing premature coronary disease in patients in their 30s and 40s, something that would have been unheard of 20 years ago.”

Doctors also see medications improving the prevention picture, says Clyde Yancy, chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, making it more urgent to use these and other measures early to control blood pressure, blood sugar and other risk factors. He was not involved in the research, but is deputy editor-in-chief at the journal.

“We need to go far upstream and think about what we can do a priori to interrupt this process,” he said of the data.

Yancy sees three explanations for the higher death rates from heart failure: first, the persistence of risk factors and the need to intervene there. “That is doable,” he said. Second, the persistence of health inequalities. “That is theoretically feasible, but it will require as much public policy as medical therapies and lifestyle change.” Third, there is the outsized influence of Covid-19, a phenomenon he says we have yet to understand.

Over the period described in the JAMA Cardiology article, doctors have become better at recognizing heart failure, Fudim and the other experts told STAT. Better testing may have contributed to an increase in heart failure diagnoses, as shown in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dataset on which the analysis was based. More people now survive a heart attack, so more people live long enough to develop heart failure, which could explain the higher prevalence in recent years.

There are limitations to the research methodology of death certificate mining, the paper’s authors note. The cause of death may not be accurate: For example, in cases of opioid overdose deaths, heart failure may have been cited when cardiac arrest was the cause, Mount Sinai’s Pinney said. The steeper rise in death rates that has coincided with Covid could mean that people sick enough to be hospitalized and later diagnosed with heart failure suffer from infection-related inflammation and economic hardship that limits their health and access to healthcare. said study author Fudim.

The data preceded the widespread introduction of the wildly popular new obesity drugs, developed to treat diabetes but which have also proven effective in improving heart health, among other things. These new drugs appear to work for heart failure patients across the entire range of ejection fraction, Pinney said.

“We need to see whether these new drugs can offset the recent worsening of cardiovascular mortality. But I think the paradox is that at a time when we’re seeing these increases in mortality, we also have access to better medicines,” he said. “We need to focus better on our healthcare systems to get the medicines to the patients. If you can administer all four classes of heart failure medications to patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, you can reduce mortality by half.”

Northwestern’s Yancy said he was neither surprised nor sobered by the investigative letter’s findings.

“This is truly a new day for those of us who have dedicated careers to heart failure,” he said. “We have gone from having very few opportunities to offer hope to a scenario where we can not only offer hope, but also talk realistically about real improvement.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health conditions is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Us financial supporters are not involved in decisions about our journalism.

![[B-SIDE Podcast] The risks of using e-cigarettes and tobacco products, especially among young people](https://blogaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/B-SIDE-Podcast-The-risks-of-using-e-cigarettes-and-tobacco-products-300x240.jpg)

![[B-SIDE Podcast] The risks of using e-cigarettes and tobacco products, especially among young people](https://blogaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/B-SIDE-Podcast-The-risks-of-using-e-cigarettes-and-tobacco-products-80x80.jpg)