Finance

The unemployment insurance program isn’t prepared for a recession: experts

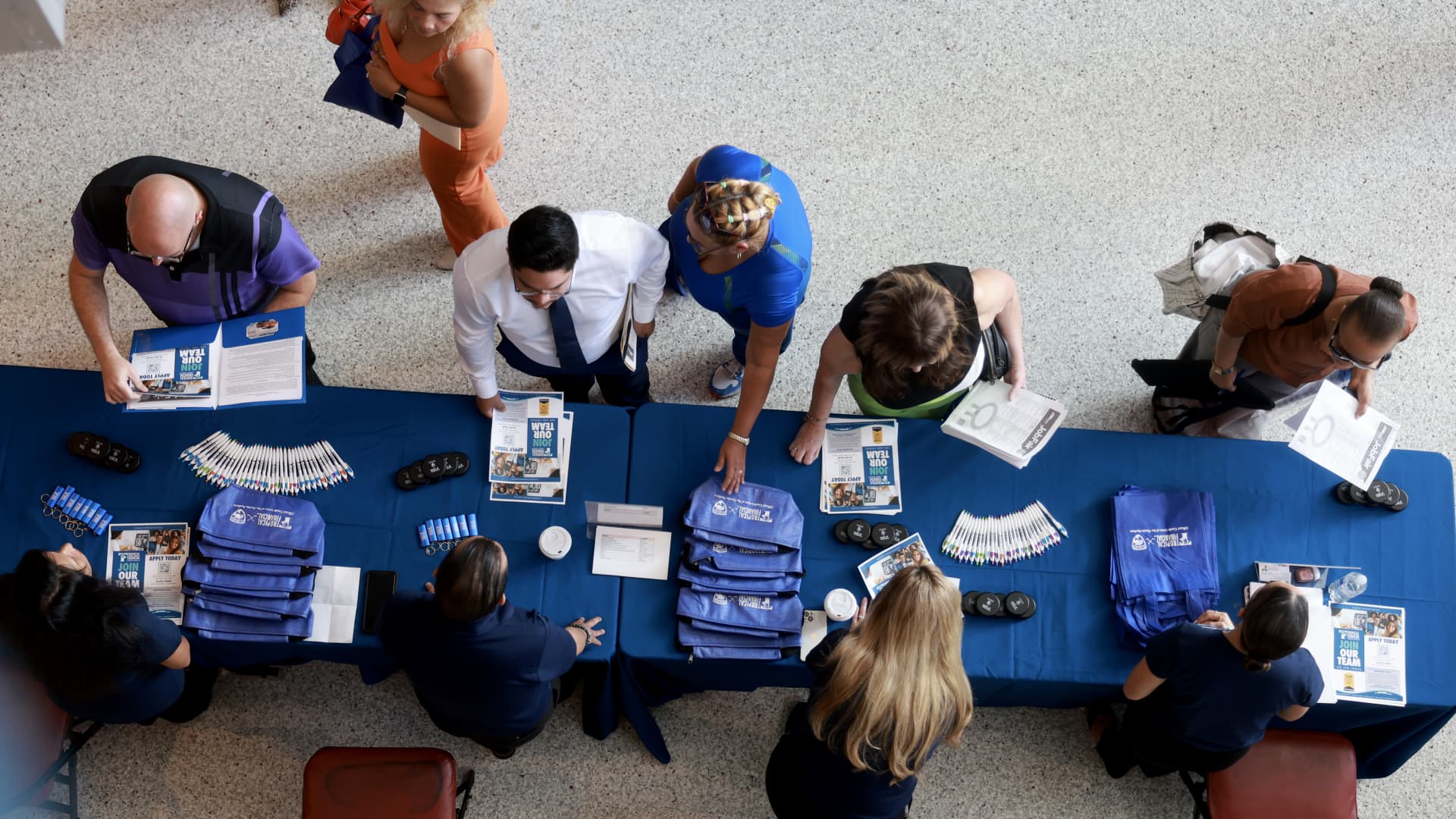

Job seekers attend the JobNewsUSA.com South Florida Job Fair on June 26, 2024 in Sunrise, Florida.

Joe Raedle | Getty Images

Renewed fears of a recession in the US have put a spotlight on unemployment.

However, the system that workers rely on to collect unemployment benefits is at risk of collapsing — as was the case during the Covid-19 pandemic — if there is another economic downturn, experts say.

“It’s absolutely not” ready for the next recession, said Michele Evermore, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, and a former deputy director for policy at the U.S. Labor Department’s Office of Unemployment Insurance Modernization.

“If anything, we’re in a lot worse shape right now,” she said.

Unemployment insurance provides temporary income support to laid-off workers, supporting consumer spending and the broader U.S. economy during recessions.

The pandemic has exposed “major cracks” in the system, including “massive technological failures” and an administrative structure that is “ill-equipped” to pay out benefits quickly and accurately, according to a recent report. report published by the National Academy for Social Insurance.

There are also wide variations among states — which administer the programs — on factors such as the amount of benefits, their duration and eligibility, according to the report, authored by more than two dozen unemployment insurance experts.

“The pandemic has exposed longstanding challenges for the UI program,” Andrew Stettner, director of the Labor Department’s Office of UI Modernization, said during a recent webinar on the NASI report.

The U.S. unemployment rate, which stood at 4.3% in July, remains far from its pandemic-era peak and is low by historical standards. But over the past year, interest rates have gradually risen, fueling talk of a possible recession on the horizon.

Policymakers must address the system’s shortcomings when times are good, “so that it can deliver results even in bad times,” Stettner said.

Why the unemployment insurance program failed

Unemployment soared in the early days of the pandemic.

The national unemployment rate approached 15% in April 2020, the highest since the Great Depression, the worst downturn in the history of the industrialized world.

Applying for unemployment benefits peaked at the beginning of April 2020, the number was more than 6 million, compared to about 200,000 a week before the pandemic.

States were ill-prepared for the flood, experts said.

Meanwhile, state unemployment agencies were tasked with implementing a variety of new federal programs established by the CARES Act to improve the system. These programs increased weekly benefits, extended their duration, and provided assistance to a larger group of workers, such as those in the gig economy.

Later, states had to implement stricter fraud prevention measures when it became clear that criminals, attracted by richer benefits, were taking away money.

The result of all this: benefits for thousands of people were extremely delayed, putting severe financial pressure on many households. Others found it nearly impossible to reach customer service representatives for help.

Years later, the states have not yet fully recovered.

For example, the Labor Department generally believes that benefits are paid in a timely manner if they are provided within 21 days of an unemployment claim. About 80% of payments were made on time this year, compared to about 90% in 2019, according to the agency. facts.

It’s imperative to build a system you need “for the worst part of the business cycle,” Indivar Dutta-Gupta, a labor expert and fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, said during the recent webinar.

Possible areas to fix

Experts who authored the National Academy of Social Insurance report outlined many areas that policymakers needed to address.

Administration and technology were part of this. States entered the pandemic with funding shortfalls in 50 years, leading to “cascade failures,” the report said.

The current system is largely funded by a federal tax on employers, equivalent to $42 per year per employee. For example, the federal government could choose to increase that tax rate, the report said.

Raising such funding could help states modernize legacy technology, such as optimizing mobile access for workers and giving them access to portals 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It would also make it easier to pivot in times of crisis, experts say.

Funding is the “biggest pitfall” that causes state systems to “really deteriorate,” Dutta-Gupta said.

More from Personal Finance:

This trend in labor data is a ‘warning sign’

A ‘soft landing’ is still on the table

The average consumer now has $6,329 in credit card debt

In addition, policymakers could consider more uniform rules around the duration and amount of benefits, and who can collect them, said Evermore, author of a NASI report.

States use different formulas to determine factors such as eligibility for aid and weekly benefit payments.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the average American received $447 per week in benefits in the first quarter of 2024, replacing about 36% of their weekly wages. facts.

But the benefits vary widely from state to state. These differences are largely due to benefit formulas rather than wage differences between states, experts said.

For example, Mississippi’s average recipient received $221 per week in June 2024, while those in Washington state and Massachusetts received about $720 per week, according to the Department of Labor. facts shows.

Furthermore, 13 states currently offer less than a maximum of 26 weeks – or six months – of benefits, the report said. Many have called for a 26-week standard in all states.

Several proposals have also called for increasing weekly benefit amounts, for example to perhaps 50% or 75% of lost weekly wages, and giving some extra money per dependent.

There are reasons for optimism, Evermore said.

U.S. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden, D-Ore., Ranking Committee Member Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, and 10 cosponsors suggested bipartisan legislation in July to reform aspects of the unemployment insurance program.

“I’m pretty encouraged at this point” by the bipartisan will, Evermore said. “We need something, we need one more big bargain before we have another recession.”

Correction: Andrew Stettner is director of the Labor Department’s Office of UI Modernization. An earlier version incorrectly displayed his title.