Finance

Visions of the 21st century

Niels Bohr once said: “It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.”

I say: Prediction is not about the future, it is about the present.

Now that I am quite old, I can look back on a wide range of views on the 21st century, many of which now seem outdated. Here are just a few examples:

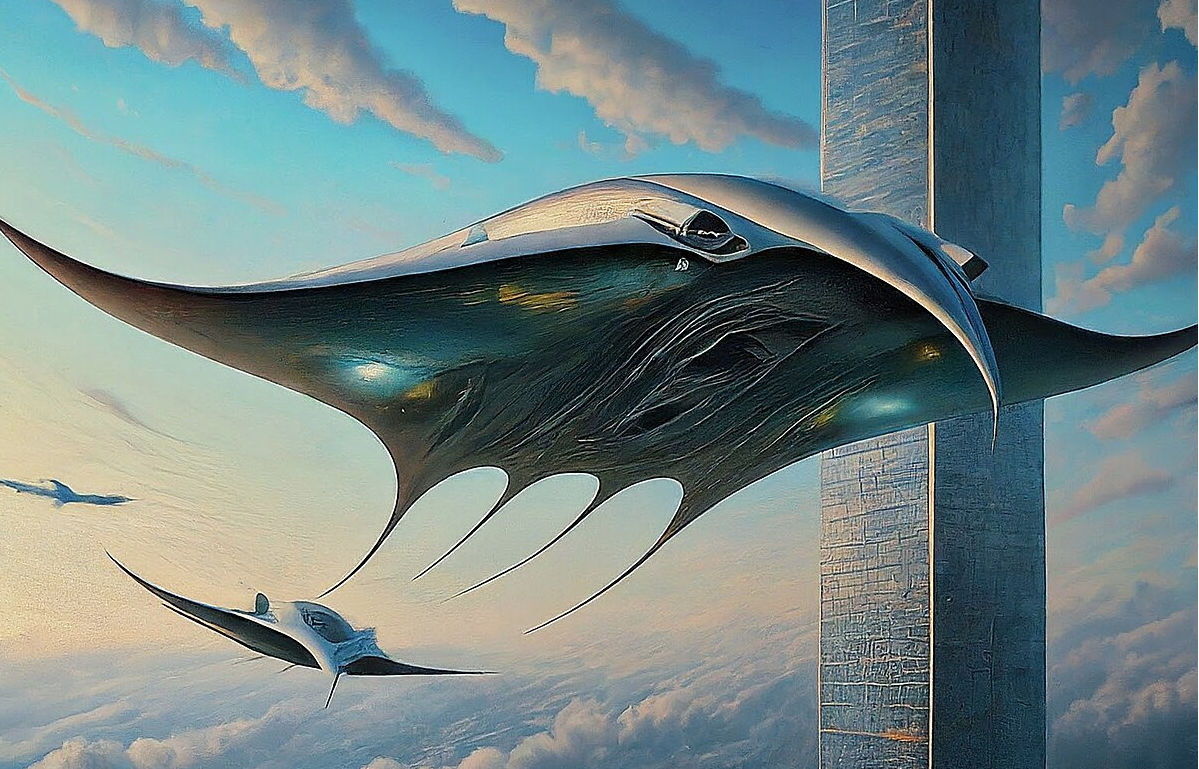

I remember the 1960s as a period of techno-optimism. There were visions of a 21st century full of space travel, supersonic planes and flying cars.

In the 1970s the mood became more pessimistic. The famous Club of Rome report warned of overpopulation and resource depletion.

In the early 1990s, there was optimism that ‘The End of History’ would usher in an era of peaceful democratic capitalism.

In the late 1990s, concerns increased that global temperatures would rise dramatically in the 21st century.

In the early 2000s, the view ‘The Clash of Civilizations’ became trendy, with a special focus on the clash between the West and the Muslim world.

Around 2010, the idea increasingly emerged that this would be the Chinese century.

A few years later, there was increasing fear of long-term stagnation.

Today, people are concerned about the rise of nationalism, declining birth rates, and fears of non-aligned AI.

What do all these views have in common? The only common thread I can see is that they all reflect what was going on at the time. That does not mean that they were all incorrect, but rather that they correlate much more closely with the circumstances of the time than with the circumstances of today.

Consider what happened when these predictions were made:

In the 1960s, transportation technology made dramatic advances over the previous decades. It was easy (but wrong) to extrapolate these trends into the 21st century. Technology continued to advance, but often in unexpected ways (biotechnology and computer chips).

In the late 1960s, world population growth peaked at just over 2% per year, a rate we may never see again. And in the early 1970s there were disruptions in the supply of food and energy.

The early 1990s saw the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

By the late 1990s, there was increasing evidence of an upward trend in global temperatures. (Some cold winters in the 1970s had led to fears of a new ice age.)

The famous terrorist attacks of September 11 led to the common belief that we would see many more such attacks in the near future. The audience felt quite vulnerable.

Expectations of a Chinese century peaked at the end of a decades-long period of double-digit Chinese economic growth.

Fears of a prolonged stagnation emerged after a slow recovery from the Great Recession and a long period of near-zero interest rates. Even I expected interest rates to remain fairly low.

So what’s in the news today? We are seeing reports of a dramatic decline in fertility. We see news of a rise in nationalism. We see warnings that AI poses an existential threat. If there is a common thread in all these concerns, you might describe it as “anxiety about the Great Replacement.” People worry that sharply declining birth rates in advanced countries will lead to our replacement with cheap labor from poor countries and increasingly sophisticated robots.

But how long will it take before these current concerns are replaced by a whole new set of concerns?

I will not try to predict the future course of the 21st century, but I will try to predict the future course of the 21st century predictions. Ten years from now, I expect the consensus forecast for the rest of the century will largely reflect the headline news stories of the 2030s. I predict that predictions for the rest of the century in the 1940s will largely reflect the headline news stories of that decade. Ditto for the 2050s. What will those news stories be? I have no idea. But I am convinced that predictions about the future will continue to reflect current events, and most of the time this will not be the case the actual future that plays out over time.

In other words: expect the unexpected. And then expect people to assume that the unexpected will become the new norm, until it is replaced by another unexpected event.