Technology

‘What goes up must come down:’ Junk satellites pose an imminent danger

Elon Musk’s SpaceX and its competitors are making reliable and quite fast satellite internet service possible thanks to a growing armada of glittering satellites orbiting overhead. Through his constellation of more than 6,000500-pound satellites, SpaceX’s Starlink internet service al reportedly provides broadband to approximately three million users worldwide, some in remote locations not served by traditional Internet providers. But what happens when all those aging satellites no longer serve their purpose?

A new one report of the environmental advocacy group PIRG warns that the current approach to dismantling old satellites, which usually involves burning them to a crisp when they reenter the atmosphere, lacks meaningful rules and regulations. That lack of oversight, they say, could lead to an increase in dangerous space junk affecting Earth, especially as competing satellite internet companies rush to build and launch tens of thousands of new satellites into orbit. PIRG estimates that SpaceX alone will have 29 tons of old material in Earth’s atmosphere every day if it is able to achieve its desired goal. satellite constellation. The organization estimates that this amounts to approximately the weight of one Jeep Cherokee coming down from space every hour. At this point, no one really seems to have a good idea of the long-term consequences of all that fiery waste.

“Too much is unknown about the extent of the environmental impacts of rocket emissions, space debris and satellite reentry on our atmosphere, Earth and climate, given the sheer number of proposed satellites,” PIRG wrote in its report. “With the size of the proposed mega-satellite constellations and their availability requiring constant replenishment, we cannot look away from the environmental damage of the space industry because we assume it is science fiction. The scientific reality of environmental damage is fast approaching.”

LEO satellites are experiencing unprecedented growth

Satellites capable of providing internet date back to the early 2000s, but their numbers have increased over the past five years, largely thanks to a wave of launches by SpaceX into low Earth orbit (LEO). Satellites in low Earth orbit operating at an altitude of approximately 1,200 miles or less, which is significantly lower than geospatial satellites responsible for services like GPS and older, atrociously slow internet services. That relative proximity to the surface and their widespread coverage areas make these types of satellites ideal for wireless Internet connectivity. The International Space Station (ISS) is also maintained in LEO.

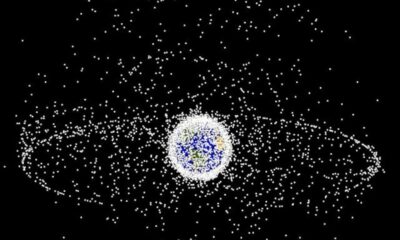

SpaceX currently has about 6,000 satellites in LEO, but has plans to expand that number to 40,000 over many years as it builds out its constellation. And Musk’s company is not alone. Competitors, especially Amazon’s Project Kuiper and OneWeb, are spend billions to launch their own constellations. China the same way plans to launch at least 15,000 satellites in the same region of space. In theory, these denser networks of satellites should lead to broader coverage, meaning faster internet for customers. It has also radically increased the amount of material flung out into space and eventually having to come back down again.

Starting this year, companies licensed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to operate in LEO are required to do so deorbit their satellites after five years. That ostensibly reduces the amount of clutter in the air, but can also increase the number of re-entry events. It also means that satellite internet companies in particular are likely to launch additional satellites to replace the ones they retired.

A crowded satellite space can increase the risk of debris or environmental damage

Space debris doesn’t always burn up before it reaches the Earth’s surface. Last year it was part of a pallet weighing approximately 0.7 kilograms removed from the ISS re-entered the planet’s atmosphere and violently smashed its way through a house in Naples, Florida. Fortunately, the homeowner was not injured. More recently, a three-foot, ninety-pound piece of rubble reportedly connected to SpaceX’s Dragon Crew-7 mission was also found by a Glamping Collective in the mountaintops of North Carolina. This Chicken Small Horror stories are rare, but PIRG and others worry this could be the case become more common as the total number of satellites filling the night sky rapidly multiplies. An increasingly crowded LEO also increases the risk of collisions between satellites and other objects, which could create dangerous debris.

SpaceX did not immediately respond Popular science request for comment.

Chunks of glowing satellite debris aren’t the only concerns. A recent one preprinted paper published by a researcher from the University of Iceland suggests that even well-executed planned re-entry creates a ‘conductive dust’ of metals that cover the Earth’s upper atmosphere. The researcher argues that high levels of aluminum and other conductive materials emitted into the atmosphere by burning satellites could lead to ‘disruptions in the magnetosphere’, theoretically allowing greater levels of cosmic rays to reach the surface.

Elsewhere, researchers from the University of Southern California write Geophysical research letters estimate of alumina pollution in the air caused by a growing number of burned satellites possess the potential to damage the Earth’s ozone layer. A reduced ozone layer allows more UV radiation to reach the Earth’s surface, which can lead to a weaker immune system and higher rates of certain cancers in humans.

“We should not rush into launching satellites on this scale without being sure that the benefits justify the potential consequences of launching these new mega-constellations, and then re-entering our atmosphere to burn up or create debris,” writes PIRG.

Stricter environmental assessments could make satellite returns safer

PIRG argues that at least some of this uncertainty about what exactly happens to all those satellites when they are ready for retirement comes from a lack of regulation. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which approves US-based satellite internet projects, has given satellite operators an environmental review exemption. This practice, which began when space operations were conducted primarily by NASA or other government agencies, has persisted over several years space age characterized by profit and privatization. Critics argue the lack of comprehensive environmental analysis in this area can lead to pollution And habitat destruction at the launch level and can continue to address environmental issues upon return. A 2022 report of the Government Accountability Office (GOA) called on the FCC to lift that exception, but has not yet done so.

“That launching 30,000 to 500,000 satellites into low Earth orbit does not even warrant an environmental analysis is contrary to common sense,” PRIG wrote.

The FCC did not immediately respond Popular science request for comment.

In addition to calling on PIRG to revise its rules around environmental reviews, the organization is calling on the FCC to immediately pause all new LEO satellite launches and “look before they start” to approve new projects. PRIG also called for an upper limit, or ceiling, on the total number of satellites deployed in orbit at any given time.

But just like it was with Leading technologists are calling on tech companies to pause generative AI developmenta meaningful slowdown in the number of new satellites seems unlikely in the short term. Some estimates suggest that LEO could be filled with as many as 58,000 satellites by the end of the decade. More satellites could improve the performance of satellite internet services, which could become attractive to the approximately 2.6 billion people worldwide who do so currently do not have broadband access due to a combination of infrastructure and cost constraints. However, stronger environmental safeguards and enforced standards around return procedures could help increase confidence as satellites become more prevalent.