Health

WHO’s Farrar: Social context is key to stopping the spread of bird flu

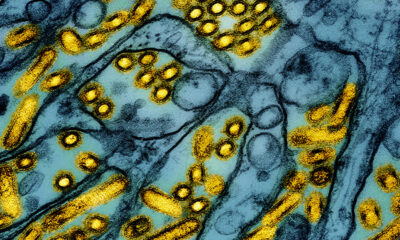

JEremy Farrar, now chief scientist of the World Health Organization, was working in Vietnam 20 years ago when the H5N1 virus began spreading across Asia – at that time among poultry. He recalls that there was reluctance among farmers to cull their chickens because they were not compensated. Moving infected birds to avoid culling only served to spread the virus, which in the years since has spread to every continent except Australia.

It’s important to keep that experience in mind, he told STAT on Monday, as the H5N1 bird flu virus is now spreading among dairy cattle in the US. Farrar emphasized that social context is critical when responding to disease threats such as H5N1, noting that similar reluctance among dairy farmers to report outbreaks or allow testing of their workers adds to the challenge of assessing the extent in which transmission takes place and what risk this entails for people.

“You can’t just separate the virus and biological surveillance from the environment and the social construct in which it happens,” Farrar said in an interview from WHO headquarters in Geneva. “That is the reality.”

Although the virus is believed to have been spreading among dairy cow herds for months, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has so far confirmed only 36 infected herds in nine states. No new outbreaks have been announced in the past week since a federal rule took effect requiring testing of a portion of cows in a cattle shipment destined to cross state lines if the cows are lactating. (The infections so far have been detected in lactating cows.)

In the field of human health, there have been several anecdotal reports of farm workers exposed to infected livestock suffering from conjunctivitis and other mild symptoms. But Todd Davis, acting chief of virology, surveillance and diagnostics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s influenza division, told a WHO webinar on Monday that only about 30 people have been tested since the outbreak was first detected in late March . There has been one confirmed infection in a Texas farm worker who had conjunctivitis.

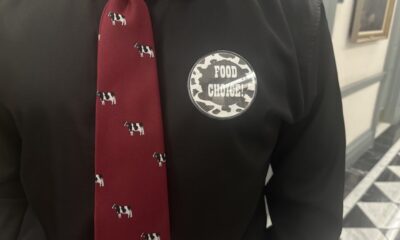

Both the USDA and the CDC have acknowledged that many farmers have been unwilling to allow testing of their animals, or to allow public health officials to talk to or administer tests to their workers. The industry is known to employ immigrant and sometimes even undocumented workers, which may explain these workers’ reluctance to comply with public health efforts to study what is going on in these outbreaks.

“I know that many people within that industry in the United States and other parts of the world are employees who are paid in some way, hourly or daily. They may be reluctant to report illnesses. It is an epidemic of a virus, but the social context in which it takes place is crucial,” said Farrar.

Ideally, public health workers would have taken blood samples from the Texas worker who tested positive for H5N1 and from people he worked and lived with, to look for undetected cases that could indicate further transmission of the virus. But he and the people he lived with refused to allow blood samples to be taken.

While he believes the risk of a human influenza pandemic caused by the H5N1 virus is low, the social context, should it occur, will also be critical, Farrar continued. The mental toll of the burdensome Covid-19 pandemic hangs over the public, healthcare workers, public health authorities and governments. Getting people to return to measures that could slow the spread, such as social distancing or school closures, would likely be difficult, he said.

“The hangover definitely applies to all societies, I think,” Farrar said. “Public health authorities, as well as healthcare workers around the world, are shattered. … It is a global phenomenon and the willingness of the world to either have vaccines, mRNA or something else, and to have school closures, masks and whatever interventions you want, would not be the same as it was in 2020.”

All the more reason, Farrar suggested, to take the measures necessary to ensure that the spread of bird flu among cows does not cause a worse crisis. “That means we better do what we can to prevent something from happening, because I think the response would understandably be very different.”