Health

Why rising measles cases in the United States are a big problem

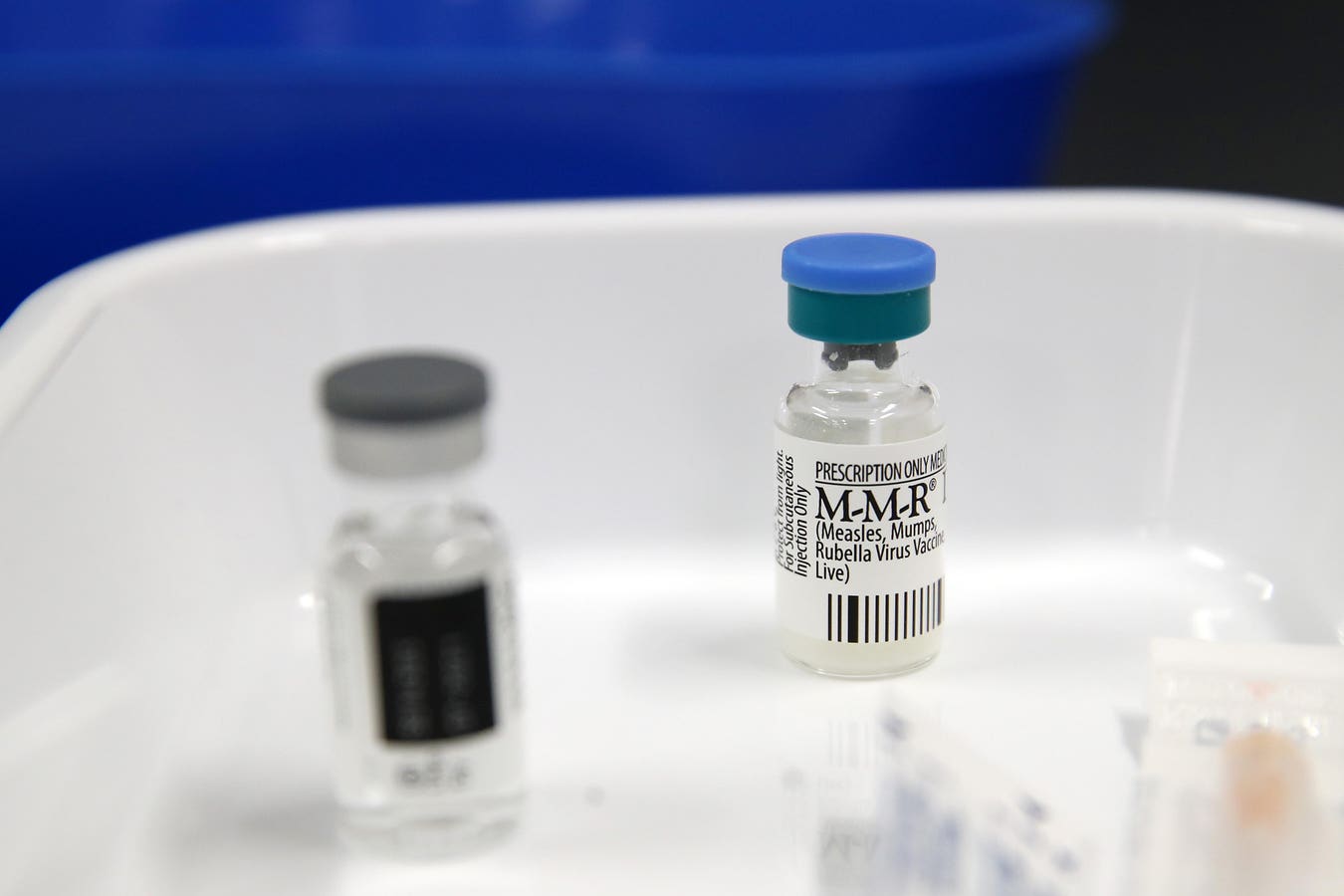

AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND – SEPTEMBER 10: Measles vaccine is being prepared in AUCKLAND on September 10, 2019 … [+]

Since January 1, 121 cases of measles have been reported in 18 states in the United Statesst this year, according to the CDC. January to March alone in 2024 represents the total number of measles cases 30% of the total number of cases reported since the beginning of 2020.

To put this in perspective, there were 13 cases of measles reported in 2020, 49 in 2021, 121 in 2022, 58 in 2023 and now 121 this year. The rise in cases is particularly troubling because the US has considered measles eradicated since 2000, meaning the disease should no longer be persistent despite occasional outbreaks.

The rising number of cases is problematic for many reasons. The number of cases is rising largely due to international travel and declining vaccination rates among children. Low vaccination rates threaten herd immunity, which refers to the protection a community receives against an infectious disease when a certain percentage of the population becomes immune, either through vaccination or previous exposure. In the case of measles, herd immunity is achieved when 95% of the population has been vaccinated.

However, 12 states and Washington DC have vaccination rates below 90% as of the 2022-2023 school year, according to reports from NBC News. According to the report, 82% of measles cases this year occurred in unvaccinated people or in people whose vaccination status was unknown. CDC.

More and more parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children, and this vaccine hesitancy is fueled by misinformation and false claims that vaccines are ineffective and can be linked to autism. There is, of course, no scientific evidence linking vaccine uptake with the development of autism.

More vaccine hesitancy and less herd immunity open the door for a measles resurgence in America. This disease is one of the most contagious viruses that spreads through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes. The virus can live on contaminated surfaces and remain in the air for up to two hours, and an infected person can spread the disease to 90% of the people around them if those around them are not immune. The highly contagious nature of the virus means outbreaks can escalate quickly, especially among communities with low vaccination rates and vulnerable populations.

Vulnerable individuals are at greater risk of contracting the disease as the number of cases increases. These individuals include infants who cannot be vaccinated against measles, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems; such as those on chemotherapy or organ transplant recipients. This means that during active measles outbreaks; these individuals are much more likely than the general public to experience severe illness and hospitalizations from the virus. This year alone, in the US, 56% of individuals reported to have contracted measles were hospitalized. CDC.

More cases of measles can also cause serious complications. While measles usually causes fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes and a characteristic rash; it can also lead to more serious complications. These include pneumonia, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and rarely even death.

Finally, measles outbreaks are placing significant strain on healthcare systems across the country, especially in areas where vaccination rates are low. Hospitals overwhelmed by caring for measles patients means resources and health care personnel are diverted from caring for other sick patients. Imagine coming to the emergency room with a stomach ache and not being seen by a doctor for hours as your provider tries to de-escalate a measles outbreak in the community. This precise scenario will become a reality as the number of cases increases.

America’s rising cases of measles pose a serious public health threat to us all; and yet it could be completely prevented through the introduction of vaccines. Children are usually vaccinated with the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine between the ages of 12 and 15 months and again between the ages of 4 and 6 years. The first dose is 93% effective at preventing measles, and the second is 97% effective.

What parent wouldn’t want to protect their child?