Health

Could bird flu be the next Covid-19?

BANBURY, UNITED KINGDOM: A man in a protective suit walks past a sign warning of an outbreak of … [+]

In early April, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) informed the public that a person in Texas had tested positive for highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) or bird flu. This person experienced conjunctivitis – or redness of the eyes – as the only symptom after being exposed to dairy cattle believed to be infected with HPAI. This was the second documented human case of bird flu in the United States since 2022, and has escalated concerns about a major outbreak – or possibly a pandemic – among the human population.

What is highly pathogenic bird flu?

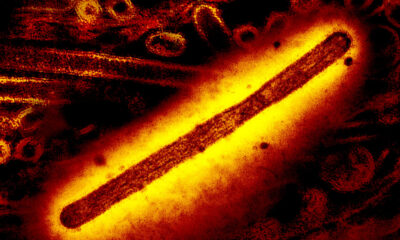

Influenza viruses, which cause annual epidemics of mild to severe respiratory illness, are not unique to humans. Certain subtypes of flu are circulating animals, including birds, pigs, horses, dogs and bats. Infection in some animals, such as wild waterfowl, can be asymptomatic (that is, no disease results from the infection) and these animals are considered a natural reservoir for the virus. However, transmission of the virus to other animals, such as backyard bird flocks or commercial poultry, can have devastating consequences.

Since January 2022, the largest outbreak of bird flu in history has occurred worldwide. To date, a subtype of highly pathogenic bird flu – known as H5N1 – has been found in more than 9,000 wild birds, affecting more than 90 million poultry worldwide. United States. Recently, the virus has been identified in certain mammals, including dairy cattle, raising concerns that the virus may be adapting for more efficient transmission between mammalian species. Although sequencing studies have not yet shown this to be the case, the recent human case in Texas has some asking: “Could bird flu lead to the next pandemic?”

A highly pathogenic strain of bird flu, known as H5N1, has affected more than 90 million people … [+]

How is bird flu different from Covid-19?

In early 2020, a new virus – now known as SARS-CoV-2 – began circulating around the world. The human population had no prior immunity to this virus, no vaccines or treatments existed, and there was limited understanding of how the virus was transmitted and the mechanisms by which it caused disease. These factors have contributed to the Covid-19 pandemic, which has led to more than 700 million cases and 7 million deaths worldwide. While HPAI has the potential to cause a significant outbreak in the human population, there are several significant differences between HPAI that make a global pandemic on the scale of Covid-19 less likely.

We have known about H5N1 for almost three decades

The highly pathogenic subtype of bird flu, H5N1, was first identified in southern China 1996 during an outbreak among domesticated waterfowl, and resulted in more than 850 human infections with a mortality rate of more than 50%. Since then, this influenza virus, as well as other low and highly pathogenic subtypes, has caused outbreaks in animals, and less commonly in humans. This has allowed researchers, infectious disease specialists, and public health officials to study these viruses and gain valuable insights into their transmission, pathogenicity, and potential treatments.

Some existing flu tests can detect bird flu

One of the biggest challenges during the early weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic was not being able to identify who was infected. This left cases undiagnosed and fueled the spread of the virus. In contrast, some of the tests we currently use to diagnose human flu – especially molecular tests (e.g. PCR) – will detect avian flu strains, including H5N1. However, most cannot sub-type the virus. In other words, existing flu tests can tell us that we have been infected with an influenza virus, but are unable to distinguish a common human subtype, such as H3N2, from an avian subtype, such as H5N1. The CDC is currently working with test manufacturers and clinical laboratories to develop tests specific to highly pathogenic avian flu strains.

We have an advantage in vaccines and antivirals against bird flu

Because we have known about HPAI for almost thirty years, this has given researchers time to research and develop tools for prevention and treatment. There is a candidate vaccine against H5N1, and studies have shown that it should induce a robust immune response against the currently circulating avian influenza subtype. The US CDC has shared this vaccine candidate with vaccine manufacturers so that production and deployment can occur quickly if necessary. Additionally, there are multiple FDA-approved antiviral medications used to treat human influenza facts suggest that these treatments are also effective against HPAI. These existing antiviral drugs would help reduce the incidence of severe HPAI cases and deaths.

What can you do to help prevent an outbreak of HPAI in humans?

Although the current risk of a human outbreak of HPAI is low, there are still several steps you can take. First and foremost, avoid contact with animals, especially birds or livestock, that are sick or have died. If you must come into contact with these animals, wear eye protection, an N95 respirator and gloves. And finally, get tested for the flu and notify your local or state public health officials if you develop symptoms — including sore throat, cough, fever, body aches, or conjunctivitis — after being exposed to an animal that may have HPAI.