Health

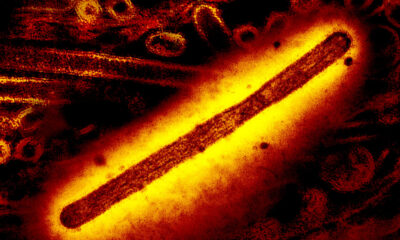

Milk tests show that the outbreak of H5N1 bird flu in cows is likely widespread

aNdrew Bowman, a veterinary epidemiologist at Ohio State University, had a hunch. He had been struck by the huge amounts of H5N1 virus he had seen in the milk of cows infected with bird flu, and thought that at least some of the virus was leaving the farms and ending up downstream on store shelves.

He knew the Food and Drug Administration was conducting its own national investigation into the milk supply. But he was impatient. So he and a graduate student went on a road trip: They collected 150 commercial dairy products from the Midwest, representing dairy processing plants in 10 different states, including some where herds have tested positive for H5N1. Genetic testing found viral RNA in 58 samples, he told STAT.

The researchers expect that additional laboratory studies currently underway will show that these samples do not contain any live virus that could cause human infections, meaning that the risk of pasteurized milk to consumer health is still very low. But the prevalence of viral genetic material in the products they sampled suggests that the H5N1 outbreak is likely much more widespread among dairy cows than official counts indicate. So far, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has reported that 33 herds in eight states have tested positive for H5N1.

“The fact that you go into a supermarket and 30% to 40% of those samples test positive suggests that there is more of the virus out there than is currently recognized,” said Richard Webby, a flu virologist who analyzed the samples. at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, where he directs the WHO Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals.

Earlier this week, the FDA announced that its efforts had found evidence of the H5N1 virus in samples of milk purchased on store shelves, but did not provide detailed results. On Thursday, the FDA announced a high-level readout from the agency’s investigation during an online symposium hosted by the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. The results returned Thursday morning showed PCR-positive milk in 20% of samples, “perhaps with some predominance for areas with known herds,” said Donald Prater, acting director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. He did not say how many samples the FDA had analyzed or from what geographic area.

The PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests revealed only genetic traces of the virus, no evidence that it is alive or contagious. The FDA believes that H5N1, which is heat sensitive, is most likely killed by the pasteurization process.

The agency is still assessing these samples for viral viability by attempting to grow the virus from milk found to contain H5N1 RNA. The FDA plans to release the results of these studies in the coming days. On Wednesday, Jeanne Marrazzo, the new director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters that a team of NIAID-funded researchers had early data indicating that pasteurization appears to be effective.

The team that produced this data – the St. Jude and OSU groups – told STAT that it has so far analyzed four samples of store-bought milk that tested positive for H5N1 genetic material via PCR. “We did the viral growth tests to see if we could get a virus out of it, but we couldn’t,” Webby said.

These four samples came from an initial collection of 22 commercial milk products purchased in the Columbus, Ohio area. “Basically I was just exploring the five grocery stores between campus and my house,” Bowman said.

PCR testing at OSU showed that three of these 22 products were positive for viral RNA. Bowman sent them to Webby to inject them into plates of mammalian cells and fertilized chicken eggs and look for signs of active viral replication. To do that, Webby needed a negative control, so he went to buy milk at a store near his lab in Memphis. But PCR testing also found H5N1 RNA in that sample, making it useless as a negative control but providing an additional data point showing a lack of live virus.

That sample is still in Webby’s refrigerator at home. He used it to make dinner earlier this week. “I’m not worried about any of it,” he said.

Although the risk of infection from dairy products is very low, the concern is that the more widely H5N1 spreads among cows, the more opportunities the virus has to adapt to transmit efficiently to mammalian hosts. It also increases the chance that H5N1 will get into pigs, where it can exchange genes and form hybrids with other flu viruses. Viruses that mutate to spread easily through one species of mammals could find it easier to infect humans.

The St. Jude group is now repeating its analyzes with the additional samples that Bowman and his graduate student purchased in the Midwest. Their initial findings provide further evidence that H5N1 is spreading widely among dairy cows in the US

This week, researchers examining viral genome sequences released Sunday by the USDA found that the outbreak has likely been going on for months longer than previously known. “Both data – the milk data and the genetic data that show this has been going on since December of last year – suggest that the outbreak is probably much bigger than we know,” said Angie Rasmussen, a virologist who studies emerging zoonotic pathogens. the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

It could also indicate that herds could be contagious with only mild symptoms or no symptoms at all, which would complicate the response and make containment much more difficult.

“What this tells us is that we are probably already seeing milk from asymptomatic infected cows containing virus,” said Andrew Pekosz, a molecular microbiologist who studies respiratory viruses at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

So far there has only been that a report of H5N1 infections in a herd without symptoms – in North Carolina. But USDA officials have not released any further details, other than to say that milk from infected but asymptomatic cows appears unchanged.

In cows infected with H5N1, the first thing that often happens is that their appetite disappears and their activity decreases. Then their milk production dries up. In some animals, the milk they produce turns yellow and thick. “It’s something strange that seems to be unique to this particular virus,” said Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. And it’s one of the biggest warning signs dairy farmers should look out for when deciding whether to test their herds. If milk from asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic cows looks normal but may contain viruses, this would obscure the need for testing.

To truly understand the extent of the spread and the possible mechanisms of viral transmission, it is necessary to conduct widespread testing of animals with and without symptoms, said Jennifer Nuzzo, epidemiologist and director of Brown University’s Pandemic Center. “If we only test cows with external symptoms, we miss infections in cows without.”

Until this week, USDA policy did not require animal testing, recommending it only for dairy cows over 3 years of age that have had at least 150 days of lactation and are exhibiting severe clinical signs such as fever, lethargy and abnormal milk. production and loose stools.

On Wednesday, the agency issued a federal order requiring an animal to test negative for the virus before it could be transported across state lines. It also requires laboratories and state veterinarians to report to the USDA any animals that have tested positive for H5N1 or another influenza A virus. But outside of interstate travel, testing remains voluntary and is only encouraged for visibly sick animals.

Public health experts told STAT that such stringent testing criteria likely distort the true extent of the outbreak. “I haven’t seen any evidence that makes me want to allay the fear that testing practices absolutely shape what we think we know about this virus,” Nuzzo said. “We just don’t have the right data right now to tell us what’s going on.”

The situation is reminiscent, she said, of the Covid-19 pandemic. In the early weeks of that outbreak, testing was limited – limited to symptomatic individuals who had traveled to China. Meanwhile, the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread unnoticed throughout the US, as genomic analyzes would later show. Later, as at-home testing became widely available, official counts became unreliable, leaving state and local health departments in the dark.

“At least with Covid, wastewater surveillance eventually stepped in to supplement our picture,” Nuzzo said. “We don’t have that with H5N1.”

On Wednesday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said it is investigating wastewater testing for H5N1, but noted significant hurdles, including farms not connected to municipal wastewater systems and the potential for infected wild birds to confound testing of water around farms.

Requiring dairy farms to regularly test all their animals, including asymptomatic animals, is not logistically feasible given the current capacity of the state’s veterinary diagnostic laboratories, Poulsen said. He and other lab directors are already bracing for the massive increase in testing they expect to begin when the USDA order takes effect Monday. But he does think more needs to be done at the federal level to encourage farmers to test their herds.

“Right now, farms just don’t volunteer samples because they have no incentives to raise their hands,” Poulsen said. That information blackout makes it much more challenging for epidemiologists to track the virus and understand how it spreads, the exact mechanisms of which remain unclear.

“We must now do what we can to understand and contain it so that it does not turn into a pathogen with pandemic potential,” Poulsen said. “That is a real risk if we continue to ignore it.”