Health

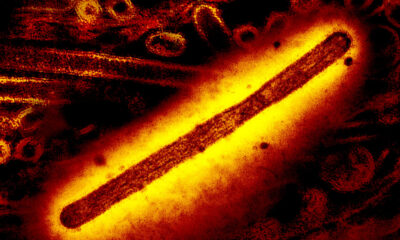

The case of the Texas bird flu virus may be the first spread from mammal to human

a New report on the first human case of bird flu linked to the outbreak in cows in the United States suggests the Texas man may be the first detected case of the H5N1 virus transmitted from a mammal to a person.

Nearly 900 people in 23 countries have been infected with the H5N1 bird flu virus since it began spreading from Southeast Asia in late 2003. But previous human cases were all linked to transmission from infected birds, usually domestic poultry.

The report, published Friday by the New England Journal of Medicine, describes the unknown man’s symptoms and his possible route of infection. It was written by scientists from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Texas Department of State Health Services and the Texas Tech University Bioterrorism Response Laboratory in Lubbock.

How the man became infected cannot be proven; While cattle on the farm where he worked reportedly suffered from a decrease in milk production and other symptoms seen in herds that tested positive for H5N1, no animal testing was conducted on that farm. However, the authors noted that nearby farms where dairy cows showed the same symptoms tested positive for the virus.

“Since the infected human was a dairy farm worker with reported exposure to sick, suspected infected cows in Texas and with no reported exposure to other mammals or birds, we believe the genetic and epidemiological data are strong evidence of human infection after exposure to suspected HPAI A(H5N1) virus-infected cows,” they wrote in the supplementary material accompanying their report.

HPAI A(H5N1) is a scientific abbreviation for the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A of the H5N1 subtype. The term “highly pathogenic” only refers to the way the virus behaves when it infects poultry, although people could easily assume it applies more broadly given how deadly this virus has proven to be in recent decades. About half of the people known to be infected died. It kills wild birds and dozens of species of mammals, including cats (domestic cats and big cats), seals, foxes, minks and many other scavenging carnivores that are unfortunate enough to consume infected wild birds.

In the report the authors describe, the man’s illness was extremely mild. His lungs were clear and he had no difficulty breathing; he had no fever. His only symptom seemed to be conjunctivitis, a condition colloquially known as pink eye.

The man and the people he lived with were given antiviral medications for the flu. He reported that his conjunctivitis had resolved. None of the people he lived with got sick.

Ideally, in these types of cases, scientists would take blood samples from the man and his contacts, as well as from other people working on the farm, to look for antibodies against the H5N1 virus. The presence of antibodies among other farm workers could indicate that the virus is being transmitted to humans more frequently than previously observed. Antibodies in the blood of the man’s contacts could indicate that he passed the infection to them, but that their cases were so mild that there were no symptoms.

But this work was not done, the report said, because the man and his contacts did not want to agree to having blood drawn. “We were also unable to collect acute or convalescent sera to assess seroconversion in dairy farm workers or household contacts,” they said. Likewise, it appears that health authorities were not allowed to investigate on the farm to see if more workers might have been infected.

The authors report that the man’s nasal swabs also showed the presence of viruses, but at much lower levels than what was found in his conjunctiva, the tissue surrounding the eye.

They hypothesize that the man could have been infected via one of two routes. Either an airborne virus in the parlor had gotten into his eyes – he was reportedly not wearing eye protection – or he had had a virus on his hands or gloves and accidentally transferred it to his eye, they suggested.

Analysis of the genetic sequence of the virus recovered from this man has shown that while it is closely related to the viruses that caused the outbreaks in cows, it does not fit neatly into the viral family tree that scientists studying the sequences have developed. The authors suggested that it is possible that the virus came from a slightly different offshoot that died off; Alternatively, there could have been more than one spillover event from birds in the Texas Panhandle region, where these outbreaks were first observed.

So far, 36 herds in nine states have tested positive for the virus, although many more herds are believed to have had outbreaks but not been tested. Both the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the CDC have acknowledged that farmers have often refused to cooperate in their efforts to investigate these outbreaks.

The report noted that the man’s virus was genetically closely related to the viruses used to produce two batches of H5N1 vaccine that the U.S. government made and stockpiled to protect against an avian flu pandemic. The stockpiled vaccine, of which about 10 million doses exist, “would likely provide immune protection in humans if used as vaccines,” the authors concluded.