Health

The HPV vaccine also prevents cancer in men. Why do so few people get it?

YYou would think that if there was a vaccine that prevented tens of thousands of cancer cases a year, people would want it for themselves and their children.

But new data released Thursday ahead of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting shows that’s just not the case.

The data showed that the vaccine reduced the risk of HPV-related cancers by 56% in men and 36% in women – figures that likely underestimate the vaccine’s effectiveness because participants in this observational study likely received the vaccine too late to fully prevent diseases. HPV infections. The data was analyzed by researchers led by Jefferson DeKloe, a research fellow at Thomas Jefferson University.

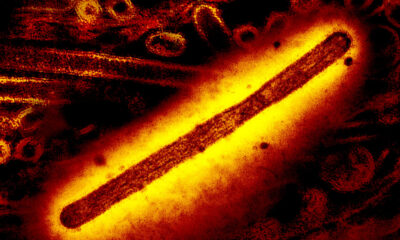

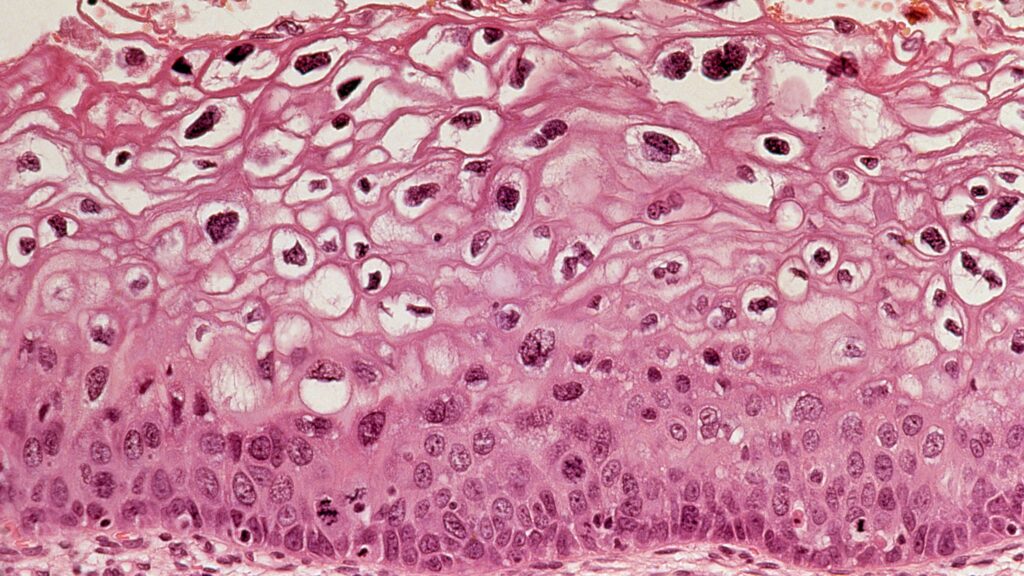

That really shouldn’t be news. Since the main HPV vaccine, Gardasil, was first introduced by Merck in 2006, it has been clear that it reduces the risk of infection with the human papillomavirus and the precancerous lesions it causes in the cervix.

But in 1999, a researcher named Maura Gillison discovered that the vaccine might have another benefit. She was one of the first to document that throat cancer in men, like cervical cancer in women, was likely caused by HPV, which is usually sexually transmitted.

Data on how well the vaccine worked in preventing throat cancer has been much slower to become available, but such cancers have proven to be a major problem. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that approximately 37,000 cancer cases are caused by HPV each year. Of these, 12,500 are oropharyngeal cancers in men and 10,500 are cancers of the cervix. In rarer cases, the virus causes cancer of the anus, penis, vagina and vulva.

The data presented at ASCO is based on HPV rates in a massive database of electronic health records of 90 million patients collected by TriNetX, a private company that uses such data to conduct observational research. The researchers were able to compare approximately 1.7 million patients who had been vaccinated against HPV with approximately the same number of control patients of the same age without prior HPV vaccination. In total, 56% were female, 53% white and 21% black/African American, with a mix of people from other backgrounds represented.

There are problems with this setup that actually make it more difficult for the vaccine. For example, it was known that some patients with cervical lesions received the vaccine after the lesions had occurred, and that people might receive the vaccine after they had already been infected with HPV, which takes many, many years to cause cancer. It’s also possible that some people who were in the control group somehow got the vaccine and it wasn’t recorded, which would make the vaccine appear less effective.

Still, the results were dramatic. Vaccinated men had 3.4 cases of HPV-related cancer per 100,000 patients, compared with 7.5 per 100,000 unvaccinated patients. Vaccinated women had 11.5 cases per 100,000 patients, compared with 15.8 per 100,000 unvaccinated patients.

We know from other studies that the vaccine can be much more effective than if given when women are young. A recent study in Scotland found that no cases of cervical cancer were found in women who were vaccinated before the age of 14.

But another study presented at ASCO found that HPV vaccination rates among adolescents and young adults in the US improved from 7.8% to 36.4% of men and from 37.7% between 2011 and March 2020. to 49.4% of women – meaning most people are still not getting vaccinated.

There are many reasons for this, including the rising tide of vaccine skepticism and hesitancy that was already present in the US before the Covid-19 pandemic. But it’s a shame.

Merck did its part ill-advised political talk when it came to the launch of Gardasil, and it certainly reaped profits from the sale of the vaccine; Revenue grew 29% last year to $8.9 billion. But the story of the vaccine was also the story of a researcher, Kathrin Jansen, who pushed through the vaccine despite internal skepticism at the drug manufacturer. She would later lead Pfizer’s vaccine efforts during the pandemic.

There isn’t really any discussion at this point about whether this vaccine could prevent tens of thousands of cancer cases per year if it were used more widely. It is a wonderful product and we should use it.