Health

The latest bird flu infection made farm workers sicker than previous cases

a The third human case of H5 bird flu linked to the ongoing U.S. outbreak in livestock has been detected in a farm worker in Michigan, health authorities confirmed Thursday.

The unnamed person worked on a dairy farm and had close contact with infected cows, the Ministry of Health said in a statement. This involves a farm different from the one where a previous human case was discovered last week.

“In this case, respiratory symptoms occurred after direct exposure to an infected cow,” Natasha Bagdasarian, medical director of the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, said in a statement. The person was not wearing protective equipment, she said.

In a separate statement, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the individual had a cough without fever and “eye discomfort” with watery discharge.

The meaning of respiratory symptoms is related to the possibility of further spread. In humans, flu is transmitted through the respiratory tract. Someone with the flu virus in their respiratory tract is more likely to spread the virus – if the virus can spread between people – than someone with an eye infection. To date, H5 viruses have not been found to spread easily among people, and Michigan and federal officials said the risk to the general public remains low.

“What the presence of respiratory symptoms tells us is that the risk of exposure is higher,” CDC Deputy Director Nirav Shah said at a news conference Thursday. “Simply put, someone who coughs is more likely to transmit the virus than someone with an eye infection such as conjunctivitis.”

The employee was given antiviral medication for the flu and is recovering. “The person has not been hospitalized. We would characterize this as a mild disease,” Bagdasarian said in an interview with STAT.

She said the farm worker was caring for sick cows and had a significant amount of exposure to the animals. Similarly, the previous case in Michigan had milk from an infected cow injected into its eye. “This is not walking past an infected animal. This is not a very transient or limited exposure,” Bagdasarian said.

The CDC said the individual was instructed to isolate, and household contacts were also offered antiviral medications. When asked whether the contacts agreed to take the drugs, Bagdasarian sidestepped the question, noting that people have the right to choose whether or not to comply.

“Generally speaking, this is all voluntary. We do not have requirements that people in certain situations have to wear personal protective equipment, that they have to undergo tests, that they have to be given Tamiflu,” she said, emphasizing that achieving compliance requires developing a good relationship between public health workers and the persons with who they work with. they interact with each other. She noted that over the course of Michigan’s response to the H5N1 situation, several people have declined to be tested and several have declined offers of antiviral medications.

To date, there are no indications of other infections at the company where the individual became infected.

“No other worker on the same farm has reported symptoms and all staff are being monitored. There is currently no evidence of person-to-person spread of A(H5N1) viruses,” the CDC said in its statement.

At least 40 people have been tested for the virus and about 350 employees are being monitored, many of them in Michigan, Shah said. “We would like to do more testing,” he added.

Also on Thursday, the Department of Agriculture announced it will put another $824 million into broader testing and surveillance for bird flu on dairy farms, and is launching a voluntary pilot program for farms to consistently test milk. If herds show no signs of H5N1 for three weeks, farmers participating in the pilot will be able to move livestock freely without having to test them.

Federal officials also said that while states are providing personal protective equipment to farmworkers, the deployment has been “mixed.” A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services told STAT last week that five states had requested equipment, mainly goggles, from the national stockpile.

State public health officials “have been trying to make personal protective equipment more available, but there just isn’t a demand for it,” said Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. The low uptake will likely continue as temperatures rise in the summer, he and federal health officials said.

Of the four known cases of H5 infection reported in the United States – three since the outbreak began in cattle – this is the first in which an infected individual reported respiratory symptoms. The two human cases reported earlier this year involved only conjunctivitis – known as pink eye. These cases occurred in Texas and Michigan, both in farm workers who had had contact with infected cows.

The first US case of H5N1 occurred in April 2022 and involved a man in Colorado involved in culling chickens at a poultry farm where the virus had broken out; although he tested positive for the virus, he reported feeling only fatigue.

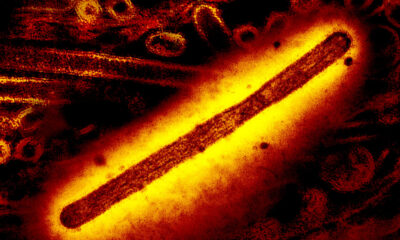

Michigan’s statement described the virus in the new case only as an H5 virus. The CDC, which conducts confirmatory testing for H5N1 cases, said it is trying to generate a complete genetic sequence of the virus and if the efforts are successful, it will release further information within a day or two.

Before this outbreak, it was not believed that cattle could be infected with this virus — an assumption that likely contributed to the slow realization that a mysterious illness that affected milk production in some dairy herds in the Texas Panhandle starting in February was actually bird flu.

Since announcing in late March that H5N1 was the reason for the decline in milk production, the USDA has confirmed 69 infected herds in nine states. One of the herds consisted of alpacas, the rest consisted of dairy cattle.

Infectious disease experts suspect the outbreak is more widespread than the number of confirmed states suggests, a belief supported by a study of commercially purchased milk conducted by the Food and Drug Administration. Of the nearly 300 pasteurized milk products purchased in 38 states, 1 in 5 tested positive on polymerase chain reaction tests for the H5N1 virus. Attempts to grow viable virus from milk that tested positive failed, supporting the FDA’s position that pasteurization kills the virus.

However, there are concerns that unpasteurized milk – commonly called raw milk – could expose consumers to dangerous levels of the virus if the herd that produced the milk was infected with H5N1.

A study published last week in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that mice fed raw milk known to come from infected cows made the mice so sick that they had to be euthanized. There have been multiple reports of cat deaths on farms with infected herds, and one of the infected alpacas showed neurological symptoms before dying, Sydney Kennedy, a public information officer for the Idaho State Department of Agriculture, told STAT in an email .

Although the virus is deadly in poultry and kills several species of mammals – from polar bears to foxes, from tigers in zoos to sea lions – it generally does not make cows seriously ill. As a result, there was little benefit to farmers in agreeing to have their animals tested. While cases continue to grow in most states with confirmed herds, no new state has acknowledged having infected animals since Colorado went on the list on April 25.

A federal order that took effect April 29 requires farmers to test some of the lactating cows they plan to ship across state lines, although they are required to test a maximum of 30 animals per shipment, and the farmer can choose which animals are tested . .

The USDA announced Wednesday that nearly 2,500 pre-movement tests have been conducted. It did not say how many of those tests returned positive results, and the agency did not acknowledge or respond to a STAT request for that figure.

Sarah Owermohle and Rachel Cohrs Zhang contributed reporting.