Health

The world needs the new pandemic treaty

aAt the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, 25 heads of government made an extraordinary call for a new international treaty on preventing, preparing for and responding to pandemics. For two years, the member states of the World Health Organization have been negotiating an international agreement that will be adopted by the World Health Assembly this month. Yet negotiations stalled in Geneva late Friday. Although most of the draft treaty text was “greened”, meaning accepted by the parties, member states failed to reach consensus on key issues.

With the World Health Assembly starting on Monday, negotiators simply ran out of time to reach agreement on the most controversial issues. As negotiations concluded, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: “My wish is that we will come out of the Health Assembly with new energy and inspiration, because the world still needs a pandemic treaty and the world needs to be prepared. … This is not a failure.”

This week, the World Health Assembly is due to extend its mandate to continue negotiating a pandemic agreement. We urge political leaders to set a firm deadline, either a special session of the Assembly in December or a finalization of the treaty in May 2025.

The world urgently needs global rules to reduce the risk of another pandemic, whether from H5N1 or another threat. To prevent such a disaster, we need international law to exchange scientific information in real time, fairly distribute medicines and vaccines, build global manufacturing capacity and restore trust between countries. Advances in technologies – such as synthetic biology powered by artificial intelligence – threaten to enable a wide range of nefarious actors to create and potentially improve upon new pathogens.

The next pandemic may be closer than we realize, and extending negotiations – whether six or 12 months – requires a careful balance between allowing enough additional time to reach consensus and having a prepared international community.

Prevention and one health

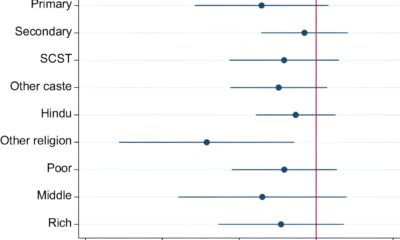

Preventing new outbreaks is crucial to prevent the next crisis. With an estimated 60% to 75% of new or emerging infectious diseases being of zoonotic origin, we must address animal health threats before they can spill over into human health threats. In new research just publishedThe loss of biodiversity, climate change and chemical pollution have all been found to contribute to the onset of diseases. A One Health approach recognizes the intersections between animal health, human health and the environment. Global regulation of land use and deforestation, wildlife trade, intensive agriculture and the excessive use of antibiotics in farm animalsand wet markets (which probably was created by Covid-19) could all help prevent zoonotic spillovers. Protecting dairy farmersfor example, could help prevent a wider human outbreak of H5N1 flu. Although One Health was strongly contested by delegates, by the end of the talks important steps forward were in sight, including negotiations on an annex to the Convention on Prevention and One Health.

Quick access to pathogen samples and sequences

When an outbreak does occur, countries must share scientific information in real time to prevent spread and develop life-saving vaccines and medicines. China for example didn’t work quickly share information with WHO early in the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition to epidemiological data, countries need to quickly and comprehensively share pathogen samples and associated genetic sequence data. These are needed to detect outbreaks, track their spread and are used for the development of diagnostics, therapies and vaccines. Despite this, the international legal system does not require this sharing, and arguably discourages scholarly exchange. Every country would benefit from strong international rules for rapid access to pathogen samples and sequences.

Share the benefits fairly

Rules mandating access to pathogens must also be accompanied by binding obligations to distribute benefits fairly. If there is one message sent by low- and middle-income countries during two years of negotiations, it is that rich countries and industry are exploiting samples and sequences of pathogens by developing life-saving products and then hoarding them. Ensuring that medical countermeasures are distributed fairly based on public health risk, need and demand is critical to stopping epidemics before they become pandemics and preventing the emergence of dangerous variants.

Rules for fair benefit sharing ensure consistency with international lawlike the Nagoya Protocol, developed to address the historical and ongoing unequal exploitation of genetic resources. Ensuring vaccine justice would rebuild trust between the North and South that was damaged during the Covid-19 crisis and in turn improve cooperation to prevent and deter outbreaks in the future. A recent proposal was to develop a separate legal instrument covering a Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing System (PABS), to be negotiated over a two-year period. When extending negotiations on a pandemic agreement, it is important that Member States do not lose the urgency of developing the PABS system by further delaying it.

Build global vaccine capacities

Access to pathogens and benefit sharing is just one aspect of vaccine equity. Only 1% of Covid-19 vaccine doses were delivered to low-income countries in the year after they were available in high-income countries, sustained by the concentration of productive capacity in the Global North and the pre-purchasing a global vaccine supply. There are clear solutions, such as securing financial resources to build regional research and manufacturing facilities, securing supply chains, and transferring the technology needed to produce medical products. These are all highly contentious areas in pandemic agreement drafts.

Restore global trust

Restoring trust between countries is essential for global health. Without trust, countries will not report outbreaks quickly and will not freely exchange epidemiological information, virus samples and sequencing data. The pandemic agreement, like the climate treaties, should create an independent Conference of Parties (COP) that would monitor and facilitate compliance, hold governments to account and create new forms of regulation to strengthen global health security. Politically, one authorized COP could increase public and political awareness of pandemic threats.

Improving the negotiation process

If negotiations are extended, Member States should consider changing the processes and format of negotiations to increase the chances of reaching an agreement. This should include enabling parallel negotiations and informal processes to facilitate progress on outstanding issues. The negotiations should also be more transparent, allowing civil society and academia to observe the procedures and assist with technical and legal challenges. This would also facilitate public observation of the process, address misunderstandings about the treaty and build confidence in the process and the treaty itself.

Just over two years ago, and guided by the principle of solidarity, Member States agreed to start negotiations, highlighting the need to address critical gaps in pandemic prevention, preparedness and response, while prioritizing the need for equity. Considerable time and financial resources have been spent on the negotiations. With elections in hand more than 64 countries Time is of the essence worldwide this year, including in the United States. For all those we have lost to the pandemic, and to save lives in the next pandemic, it is high time to safer and fairer world for ourselves and our children.

Alexandra L. Phelan is an associate professor and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and faculty director (policy) at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Planetary Health. Lawrence O. Gostin is a distinguished professor of global health law at the O’Neill Institute, Georgetown University Law Center, and director of the WHO Center on Global Health Law. His book “Global Healthcare Security: A Blueprint for the Future” is published by Harvard University Press (2021).

Disclosure: Gostin supported WHO in drafting and negotiating the pandemic agreement and is a member of the WHO International Review Committee on the International Health Regulations. Phelan has been involved in the negotiations as a relevant stakeholder and has informally advised the Member States on the pandemic treaty.